The quest for ethical gold – a Swiss refiner’s viewpoint

Switzerland is at the centre of the international gold trade, boasting four of the world’s top seven precious metal refineries. But this highly lucrative, strategic sector has a poor environmental and human rights records. Gold extraction is risky and can even be fatal – as shown by the fire in May at La Esperanza mine in Peru that left 27 people dead. SWI visited Metalor and spoke to its CEO about the challenges of due diligence in a fiercely competitive industry where few believe in the merits of transparency.

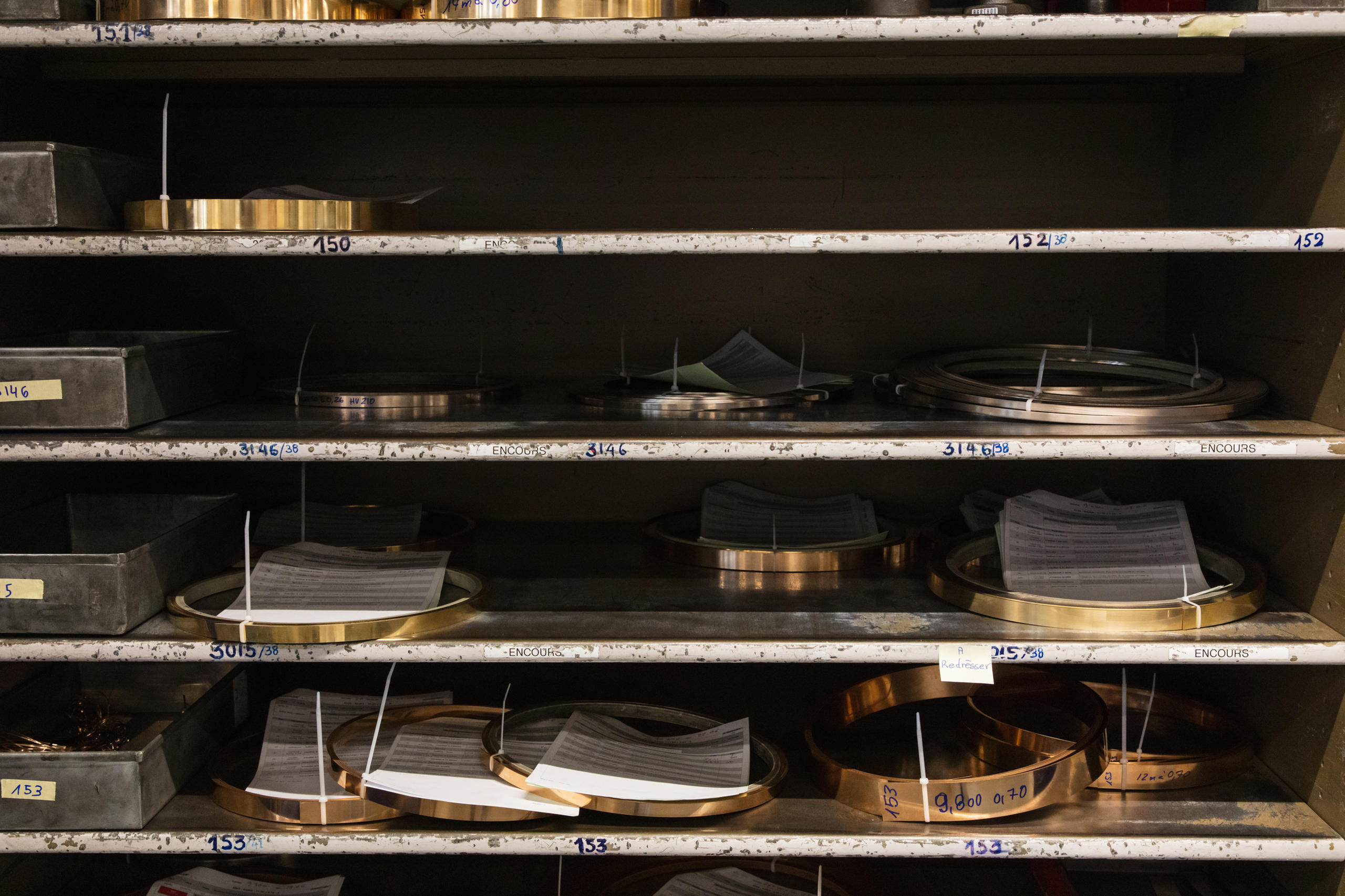

Enclosed by corrugated metal walls, Metalor’s refinery in the town of Marin in Switzerland’s west, is low-key with the feel of a vast grey hangar. But the collection of luxury cars parked outside and the high-tech security check at the entrance allude to the vast wealth within. Security protocols mimic those of an airport or prison, with jewelry and phones checked in on entrance, and body scans and checks of personal possessions a mandatory rite of passage as we head for the smelting chambers and pristine labs.

CEO Antoine de Montmollin guides us through the history of this gold industry gem nestled in the canton of Neuchatel (founded in 1852 and now owned by Metalor’s parent company, Tanaka Kikinzoku, a family-owned Japanese business) as well as the technicalities of smelting precious metals. Sacks of impure gold and silver mark the start of a complex process that turns out bars of gold refined to a purity of 999.9‰ and metal rings destined for banks and watchmakers. Metalor has a refining capacity of 800 tons of precious metals per year.

SWI: How exactly do you ensure that what you get is gold from legitimate sources?

Antoine de Montmollin: We have a very robust and strict due diligence system. We try to be as close as possible to customers, to suppliers of gold, to make sure that it’s coming from a legitimate origin. KYC, know your customer, it’s very important. We work directly either with the mines so we can check and make sure that the gold is coming from where they say it’s coming from.

We don’t compromise. If we have any doubt about any supplier of gold, we just stop.

Metalor doesn’t have gold from the Amazon and we don’t work with Russia anymore. If we can’t trace the gold, we don’t take it. We will never take gold from Dubai, for example. We avoid intermediaries like collectors of artisanal mining because you can’t trace the gold.

Metalor has also developed its own traceability tool together with the University of Lausanne to help ascertain the origin of its gold.

And we undergo four audits every year: by the London Bullion Market Association, Responsible Jewellery Council, London Platinum and Palladium Market, and by Swiss authorities. Basically, they select at least 30-40 gold providers and go through the files and make sure that all the documents are full and complete. They also check the transactions.

SWI: How many mines do you work with worldwide? And how do you ensure that at these mines, labour and environmental conditions are sound, that there’s no human rights abuses?

A.M.: It’s mainly Africa. Roughly 20, 25 mines. They are all industrial mines belonging to major companies. Image is very important as they are listed on the stock market and they really have very strict policies. So we trust them, we work closely with them, and we believe that they are doing the right thing. At least once a year we visit them and discuss any potential issues. We are confident that all our suppliers of gold from industrial mines are respectful of the environment and human rights.

SWI: You had mixed experiences with artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM). You pulled out of Africa and South America but re-engaged in Peru. What’s the challenge?

A.M.: It’s a big challenge. Metalor cannot manage all the traceability and the supply chain of artisanal mining by itself. We need support, local support, either by NGOs or local authorities. This the only way we are going to reach the target to improve the condition of artisanal mining.

In 2014 we pulled out from Africa because we couldn’t control the supply chain. And this is a reason as well we stopped artisanal mining in South America in 2019. Now we have a good project with the Swiss Better Gold Association in Peru, and I believe this is a way to work in the future: always in collaboration with an NGO or local association, local governments.

Artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) covers a range of activity from informal individual miners earning a subsistence living to more formal and regulated small-scale entities producing minerals commercially. This informal economic sector employs 40 million people globally, 10 million of them in sub-Saharan Africa, according to the World Bank. Some countries distinguish between between ‘artisanal mining’ that is purely manual and on a very small scale, and ‘small-scale mining’ that has some mechanisation and is on a larger scale. Some countries are working to formalise artisanal mining activity, which has been linked with environmental and health problems due to the use of mercury, which is used to extract gold from ore, as well as deforestation and human/labour rights abuses. Switzerland has been supporting such efforts through the Swiss Better Gold Initiative, a public-private partnership promoting gold from responsibility extracted artisanal and small-scale mines in Peru, Bolivia, Colombia and Brazil.

SWI: But 27 people were killed in a mining accident at the project in Peru in May. Do you know what happened exactly and what this means for future of the project?

A.M.: It’s a tragic accident and it’s difficult to find the right words to describe such a tragedy. I think what’s important now is to wait the cause exactly of what did happen. When we know the reason of this accident, we will take the lesson from there to make sure that it will not happen again.

SWI: Are you considering working with artisanal and small-scale gold miners in more parts of the world? What’s the business case for doing so?

A.M.: Yes, if we have good partners and a good project.

There is no business case for Metalor. You have to segregate the ASM material and refine it in separate lots so we can keep its full traceability to be able to sell it after to the market saying: this gold is coming from this specific mine. It is a lot of work. You have to clean the reactor every time. And then the final buyer still needs to pay a premium, part of which goes back to projects that improve working conditions at the mine.

It’s not easy to find someone willing to buy this gold with a premium. As soon as you have a premium, people tend not to buy, unless you have a customer that believes it makes sense and it’s for a good cause.

We’re talking about a few francs a kilo. But when you look at the price of a kilo of gold, which is up to CHF50,000-CHF55,000, what is a few francs more?

The premium is CHF1 per gramme. So that’s CHF1000 per kilo and 70% of it, CHF700, goes back to the mine to support social and environmental projects, and 15% is invested into technical assistance. It’s not a huge amount. I think watchmakers [who use gold] are starting to realise that.

There has been some progress but it’s a day-to-day challenge to be able to sell this gold. For Metalor there is absolutely no economic gain on this.

SWI: How would you describe the Swiss Better Gold Initiative in terms of where it has succeeded and also where it has failed or not done as well as it could have?

A.M.: The idea is great. And to have the support of the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs, of the Swiss government, is also good. The problem is they need more means, more human resources to be able to check what’s going on in the field. If you take the example of Yanaquihua [Peru mine], we are talking about 300 artisanal miners. So it demands a lot of resources to be able to carry out all the controls and make sure that everything is okay.

Typically, Yanaquihua produces about 1 to 1.5 tons of gold per year. When we started the project, about three years ago, we couldn’t find any buyers for this gold. There was absolutely no interest. Now we can sell all the gold. UBS and Swiss luxury brands are buyers.

SWI: What role do consumers have to play in driving demand for ethical gold?

A.M.: If you go to a jewellery shop or watch shop and ask the seller: how many people ask where is the gold coming from? Nobody asks. I think consumers should ask the question, where is the gold coming from? Consumers have a key role to play.

Gold is one of the most sought-after metals on the planet. For thousands of years it’s been a store of value and a symbol of wealth as manifested by its widespread use in jewellery. It’s been a key component in the financial reserves of nations for centuries. It is traded on financial markets, used as a hedge against inflation and even to circumvent sanctions.

Consumers have more gold at their fingertips than they realize. The precious metal is found not just in wedding rings but also in everyday electronic devices such as iPhones, laptops, and computers. It is also used in the medical, automotive, and aerospace industries.

SWI: When will we be able to go on the Metalor website and have a map of the world with pins on every mine that works with you?

A.M.: It’s going to happen. We are in a world of transparency. Not only in the gold industry, in general. People want transparency. And I think we will have to move towards more transparency in the gold industry. If it was only my decision, I would have absolutely no problem to display all the mines we have in the world, because we have absolutely nothing to hide. Not a single problem with any single mine.

The problem is that the list of these mines are our customers. So basically, it’s what we call in French “secret d’affaires” [trade secrets]. Competition is fierce. If you give the list of all your mines to your competitors, they will be more than happy to try to secure this business instead of you.

SWI: Where do you see Metalor’s future?

A.M.: For gold and silver, definitely margins are very small. It’s very challenging economically. So the strategy is to move more to what we call PGM [Platinum Group Metals]. This is where we are going to do more added value product with higher margins. We provide palladium-based catalysts [used for hydrogeneration] to the pharma industry and we develop different types of catalysts. Tanaka is very good at fuel cells for hydrogen. They produce these in Japan. And the idea is to develop fuel cells as well in Switzerland for the European market. This is the future headline for Metalor.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.