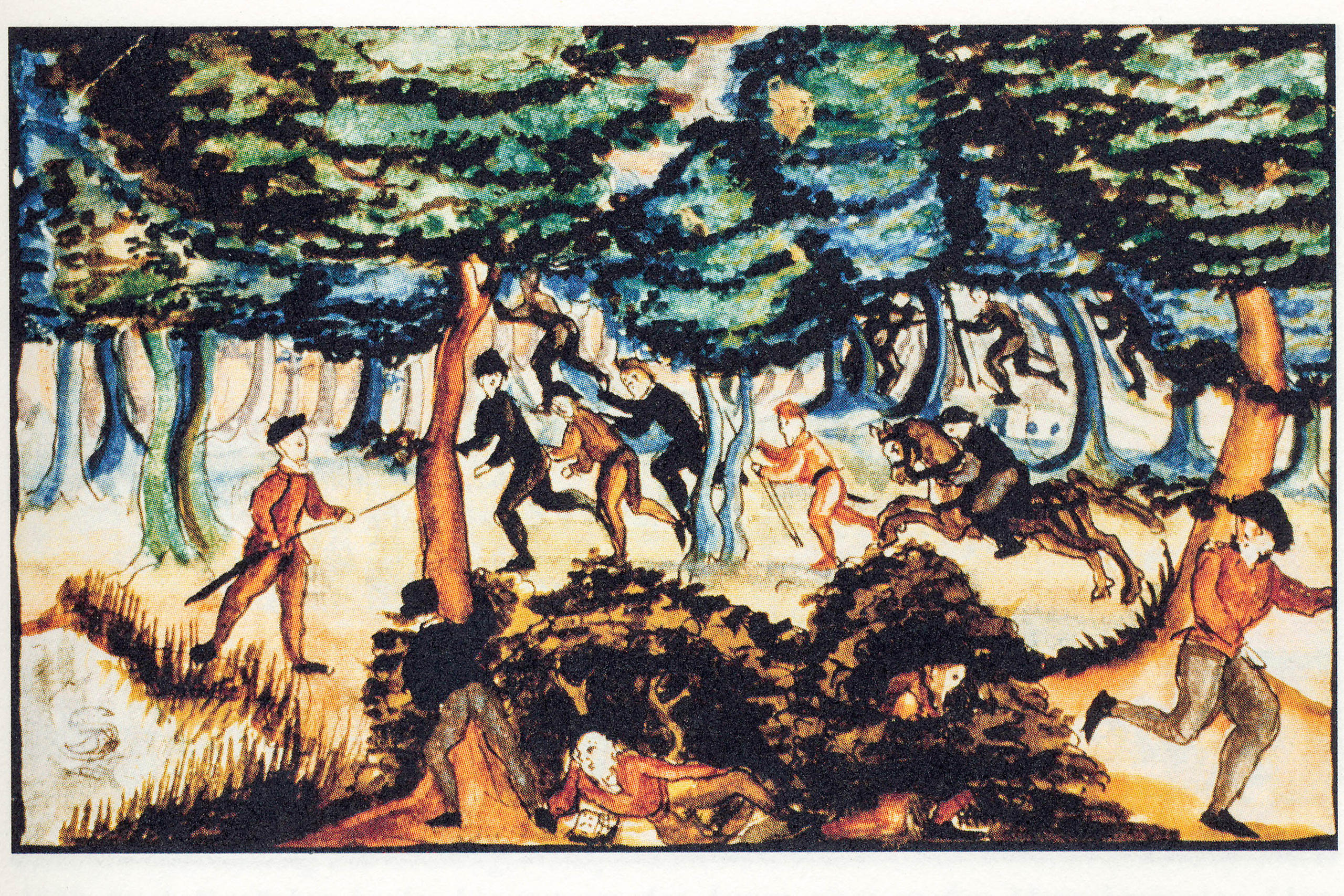

The Anabaptist Felix Manz meets a terrible end

The people of Zurich crowded along both sides of the Limmat to follow the macabre scene playing out in the middle of the river. Felix Manz, his hands and feet bound, crouched down on the deck of the fisherman’s cottage and sang a full-throated rendition of the psalm “Into thine hand I commit my spirit.”

From a skiff, a preacher lectured him verbosely, while the executioner pulled with all his might on the rope he had tied around the neck of the condemned man.

Desperate cries rang out across the water. They were from Manz’s mother, who called to him from the bank telling him to remain steadfast in his faith.

This historical account is part of a series of swissinfo.ch articles marking 500 years of the Reformation. The origin of the Reformation is generally considered to date back to the publication in Germany of the Martin Luther’s 95 Theses on October 31, 1517.

No one had expected this grisly end. Felix Manz was originally a trusted accomplice of Huldrych Zwingli and had worked together with him on a new translation of the Bible. But differences soon emerged. Manz and his friends accused Zwingli of delaying the Reformation and of making compromises with the authorities.

They were young and radical, but basically did exactly what Zwingli preached himself: they took the Holy Scripture as the only guideline for their faith and their actions. They denied, among other things, the existence of purgatory, and demanded the abolition of the holy mass and infant baptism because neither of these were mentioned anywhere in the Bible.

Professing faith

On January 17, 1525, Zwingli and his radical opponents crossed swords in public for the first time. According to Manz, baptism only made sense if the people to be baptised “are capable of professing their faith themselves.”

Zwingli disputed this, and the Zurich government came down hard on his side. It ordered all unbaptised children to be christened within a week, or their parents would have to leave the Zurich area. Four days later, it imposed a speech ban on all advocates of adult baptism. That evening, the first adult baptisms on Zurich’s soil took place in the Manz family home. It was a deliberate act of protest, similar to the sausage eating in Lent incident with which Zwingli and his radical friends launched the Reformation in Zurich — but this time the Reformer was on the same side as the authorities.

The newly baptised Felix Manz immediately began to promote adult baptism publicly. Ten days later, he was arrested, and Zwingli tried to persuade him to change his mind.

But Manz remained stubborn. After escaping prison and decamping to the Graubünden region, he continued his mission. A few months later he was arrested again and deported back to Zurich. He was “an opinionated and obstinate person,” the Chur authorities reported – not even the threat of the death penalty had stopped him from baptising adults.

Crippling taxes

The Anabaptists became ever bolder. They enjoyed great popularity among farmers, who hoped that a literal interpretation of the Bible would lead to improvements in their social status and the abolition of crippling taxes.

On a penitential procession through Zurich in the summer of 1525, the Anabaptists reviled Zwingli as a satanic dragon who was leading the world astray. They lamented at the tops of their voices: “Woe betide Zurich! Woe betide Zurich!”

The Anabaptists stirred up such a disturbance that the Zurich authorities organised a three-day scholarly debate about adult baptism for the beginning of November 1525, hoping to put an end to the problem. Interest was so great that the event had to be relocated to the Grossmünster, or Great Minister.

Felix Manz, who had been hauled out of prison especially, defended his theological position against Zwingli. The atmosphere was tense.

One Anabaptist from Zollikon demanded, “with a great deal of shouting,” that Zwingli should finally recognise the truth. Zwingli reprimanded him as a “coarse, blundering, rebellious farmer.”

It quickly became apparent that the Anabaptists were defending a lost cause. When Manz refused to stand down from his position, he and fellow believers were cast into the Witches’ Tower.

After a winter of nothing but bread and water, a court sentenced him to lifelong imprisonment at the beginning of March 1526. At almost the same time, the government passed a law threatening Anabaptist reoffenders with the death penalty.

Spectacular escape

Two weeks later Manz pulled off a spectacular escape. Together with 13 male and seven female fellow prisoners, he climbed through a hole in the roof of his cell and abseiled over the outer wall of the prison.

He once again travelled around the country preaching and baptising, until he was arrested and tried once more in early December. The court sentenced him to death by drowning “for his seditious character” and “his insurrection against the authorities.” This was a form of execution that was deemed particularly humiliating because it was usually reserved for women.

On January 5, 1527, Manz was dragged by the executioner into the ice-cold Limmat, where he died a wretched death. Shortly before his execution, he had written in prison: “Such acts are wrought by the false prophets and hypocrites of this world, who curse and plead from the same mouth, whose lives are disordered, who call on the authorities to kill us, and thereby defeat the essence of Christ.”

In 1983, the Swiss Reformed church apologised for the first time for the suffering it had caused the Anabaptists. A memorial plaque erected in 2004 on the bank of the Limmat commemorates Manz and his fellow believer Hans Landis, who was beheaded on Zurich’s Fischmarkt.

Translated from German by Catherine Hickley

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.