The terrible fate of Swiss women who lost their nationality

Until 1952, Swiss women who married foreigners automatically lost their citizenship. During the Second World War, this “marriage rule” sealed the fate of hundreds of women. Some died; others – like Bea Laskowski-Jäggli – became stateless.

“I met Wladislaw in 1945. He was a prisoner in the Büren an der Aare detention camp [for Polish soldiers, located in canton Bern]. I was working there as a nurse – the war was still raging. He had joined the Polish army in 1939 and was captured by the Germans soon after. On his third attempt, he managed to escape to Switzerland. Because he spoke German, he was quickly hired as a translator.

After the war, he had to leave for London, where the Polish government had been in exile since 1940.

We corresponded for many months. Then I said to myself, ‘If you want to be with Wladislaw, you have to get to know England.’ I found a job quickly. At that time, Swiss domestic workers were very much in demand among the English middle class. That’s how I arrived in London in 1947. I was 30.

A few months and two jobs later, my residence permit expired. What should we do? ‘Well in that case,’ we said, ‘we’ll get married. Let’s see how it goes’.

In June 1947, surrounded by friends, we made our vows. Our families, of course, could not afford to be there. But we had a wonderful day!

However, by marrying Wladislaw, I lost my Swiss citizenship. But I didn’t get Polish citizenship either. I became stateless.

At the start, many people were suspicious of us. He was Polish, I was Swiss – we were foreigners. In 1961 we both became British citizens. It was only then that things got better.”

The ‘marriage rule’

Bea Laskowski-Jäggli is one of the 85,200 women who lost their Swiss citizenship between 1848 and 1952 because of the so-called “marriage rule”.

“But this rule was only customary law,” says Silke Margherita Redolfi, a historian and author of the book Die verlorenen Töchter (The Lost Girls). “It was not anchored in either the constitution of 1848 or that of 1874, nor in civil law.”

The “marriage rule” was inherited from the former Swiss Confederation, where, according to an agreement between the cantons, a woman’s place of origin becomes that of her Swiss husband.

In theory, if a woman married a foreigner, she automatically acquired the latter’s nationality. This allowed for unity of citizenship within families and avoided dual nationalities, which at the time were not approved of. The only exception to this rule concerned a Swiss woman marrying a stateless person – in such a case, she was entitled to retain her nationality.

Foreigners in their own country

If a woman lost her Swiss citizenship, she was treated in the same way as any other foreigner in Switzerland. If she had been living abroad before the outbreak of the Second World War, then she was permitted to stay in Switzerland for a maximum of three months. If she was settled in Switzerland, she had to apply for a residence permit, which she usually obtained.

For these women, no legal recourse existed for them to retain their nationality, because “although the ‘marriage rule’ was customary law, it had the same value as any other written law,” Redolfi says.

During the war, Switzerland tightened the “marriage rule”. It was inserted into an emergency law in place during the conflict. At the same time, the authorities withdrew the Swiss passports of women who married Jews stripped of their nationality by Nazi Germany. These women then became stateless.

In 1941, there was reason to be hopeful. A clause in Article 5, paragraph 5 of the emergency law stipulated that in the most serious cases, a woman could be reintegrated into Switzerland. “Many Jewish women living abroad tried this, for obvious reasons, but the government rejected one application after another,” says Redolfi. According to the authorities, this clause only applied when the civil registrar who performed the marriage made a mistake.

So Jewish women who had previously held Swiss citizenship lost their lives in the German gas chambers. One of them was Lea Berr-Bernheim of Zurich, who was born into a Jewish family and married to a Frenchman. Arrested by the Gestapo in 1944, she and her young son Alain were deported and murdered in Auschwitz a few months later, despite her family’s appeals to the Swiss authorities.

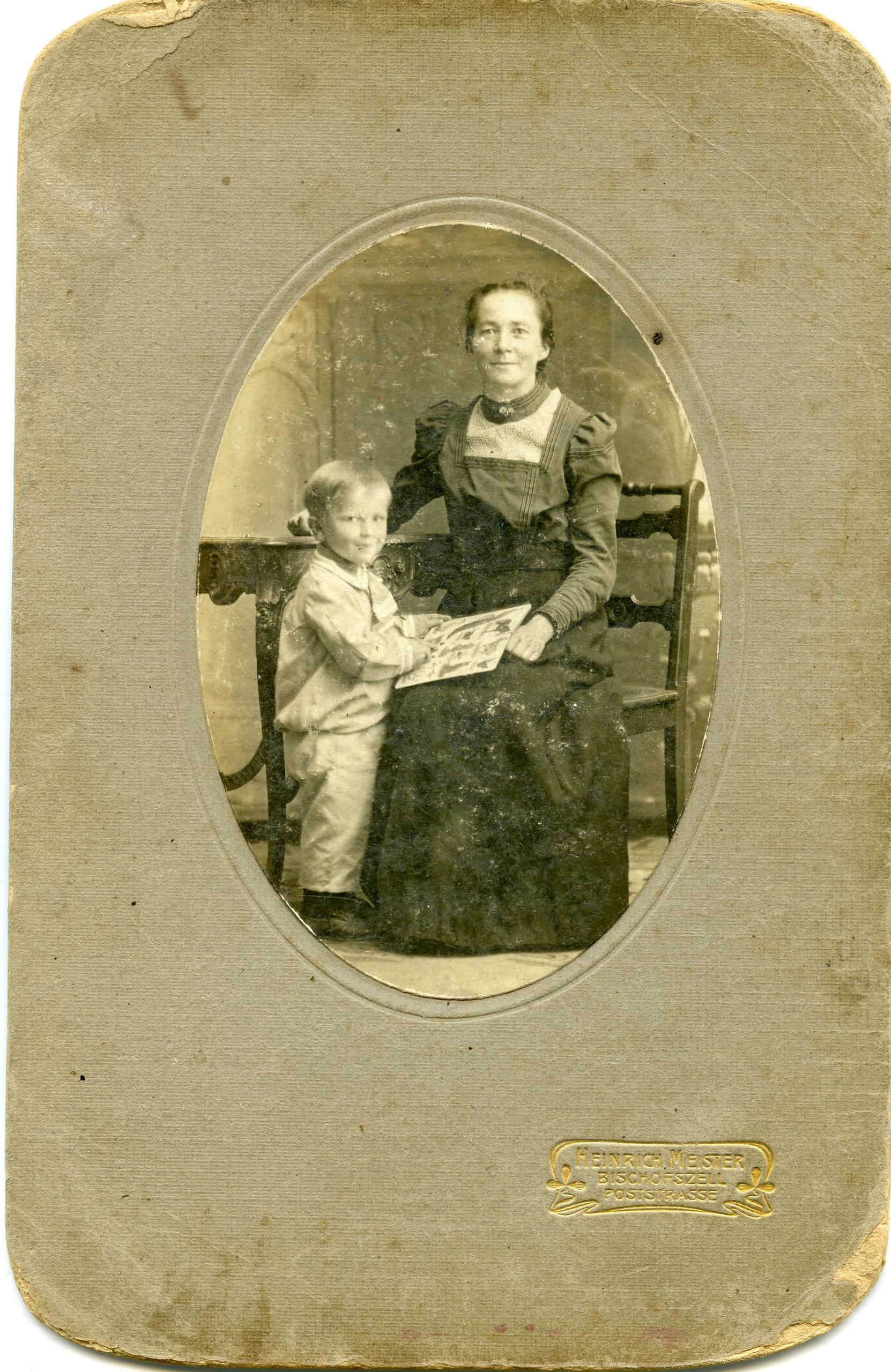

Elise Wollensack-Friedli suffered the same fate. Originally from the canton of Thurgau, she became German by marriage and was interned in a psychiatric clinic in 1922. Her home canton rejected her request to return to Switzerland in 1934 so she remained in the psychiatric hospital, where she was murdered by the Nazis in 1945.

In the midst of the war, an emergency law was in place and families had no means of challenging these decisions: the Federal Court no longer had any power.

Resistance is organised

At the end of the war, the Swiss government tried to transform the emergency law into ordinary law. The “marriage rule”, says Redolfi, “was an ideal instrument to regulate immigration and thereby avoid paying potential maintenance costs for widows, orphans or the poor, which would be borne by the community”.

The tragic fate of thousands of women raised alarm bells inside feminist organisations, which campaigned to change the law. Supported by the media and well-known politicians including Henri Guisan, who was general of the Swiss Armed Forces during the war, they succeeded in getting parliament to pass a law at the end of 1952.

This text came into force on January 1, 1953, and allowed Swiss women to declare to the civil registry office that they wished to retain their nationality. It also allowed women who had lost their nationality to apply for a reinstatement.

However, it was not until 1992 that full equality between men and women was introduced. In the meantime, many families were affected by the loss of Swiss citizenship, especially the descendants of those women who had lost their passports.

Happily ever after

The loss of Swiss citizenship had no such impact on Bea Laskowski-Jäggli’s life. She and Wladislaw both worked for many years at the Central Middlesex Hospital in west London – she as a laboratory manager, he in payroll. The couple bought a house in Ealing. They had no children.

In 1953, after the revision of the law on the “marriage rule”, Laskowski-Jäggli applied for a reinstatement and became Swiss again.

Wladislaw Laskowski died in 2006. His wife kept the promise she had made to him: she returned to live in Switzerland until her death in 2016. “I didn’t want to go back to Basel, but Wladislaw was convinced that it was the best thing for me, so I did,” she told author Simone Müller. Before that, Laskowski-Jäggli went to lay her husband’s ashes in the family vault in Jaroslaw, Poland. “No one would have cared for him if I had left him in London,” she said. “There I know he will get flowers and everything necessary.”

Laskowski-Jäggli’s (1917-2016) first-person account is loosely based on her story, told in Simone Müller’s book Alljährlich im Frühjahr schwärmen unsere jungen Mädchen nach EnglandExternal link (Every year in spring our young girls leave for England), Limmat Verlag.

Silke Margherita Redolfi, Die verlorenen TöchterExternal link, Chronos Verlag

Translated from French by Catherine Hickley/gw

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.