How Afghans see their homes in paintings of the Alps

Golbedin Husseini, Verena Meuli, Christine Thielmann and Mohamed Ewaz Baba are four strangers in a strange place.

I meet them on a clear spring evening at an exhibition they have curated.

Golbedin and Mohamed are from Afghanistan while Verena and Christine are Swiss but weren’t born in Aeschi, the alpine village that is the setting for this encounter. The four of them first got to know each other in Aeschi three years ago.

This should have been an easy story to tell: a story of how art – particularly paintings of mountain landscapes – can facilitate a dialogue between asylum seekers and local residents.

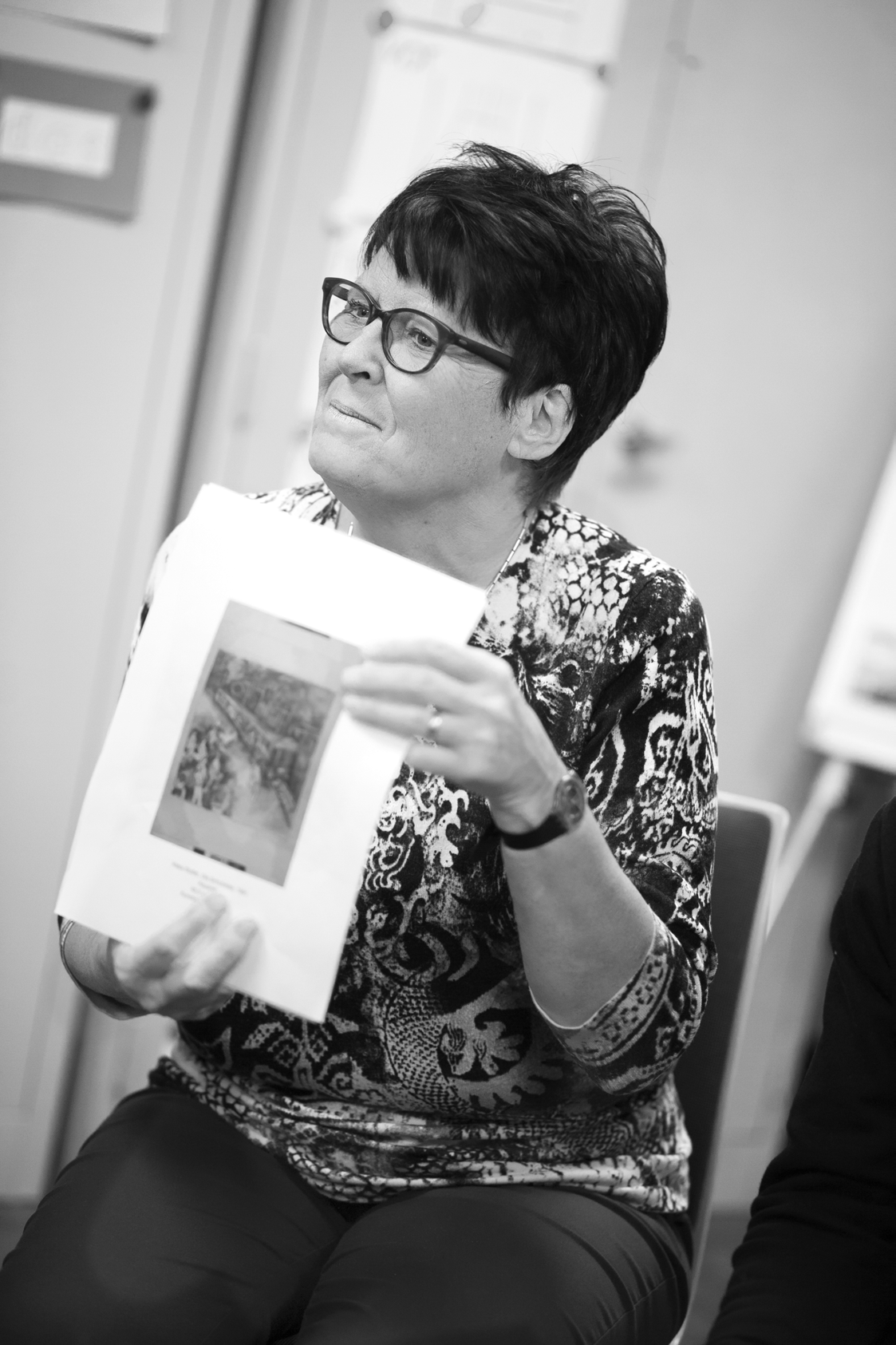

“We looked for people who lived in the mountains, and I thought it would be very interesting to ask people who are not here voluntarily – people who’ve been sent here. The other idea – although not new – is that art can bring people together to talk,” explains Rut Reinhard, an art educator at the Fine Arts Museum in the nearby town of Thun.

Uphill

Reinhard’s task was to involve people living in the surrounding mountains in projects to accompany this year’s exhibition, highlighting the Thun Panorama, the world’s oldest-known surviving panoramic painting.

Called ‘Uphill’, the show sets out to trace how our attitudes towards the Alps have changed in the 200 years since the exceptional round painting was made.

That’s why Reinhard brought Golbedin and Mohamed and a few other asylum seekers together with volunteers from the local parish, including Verena and Christine.

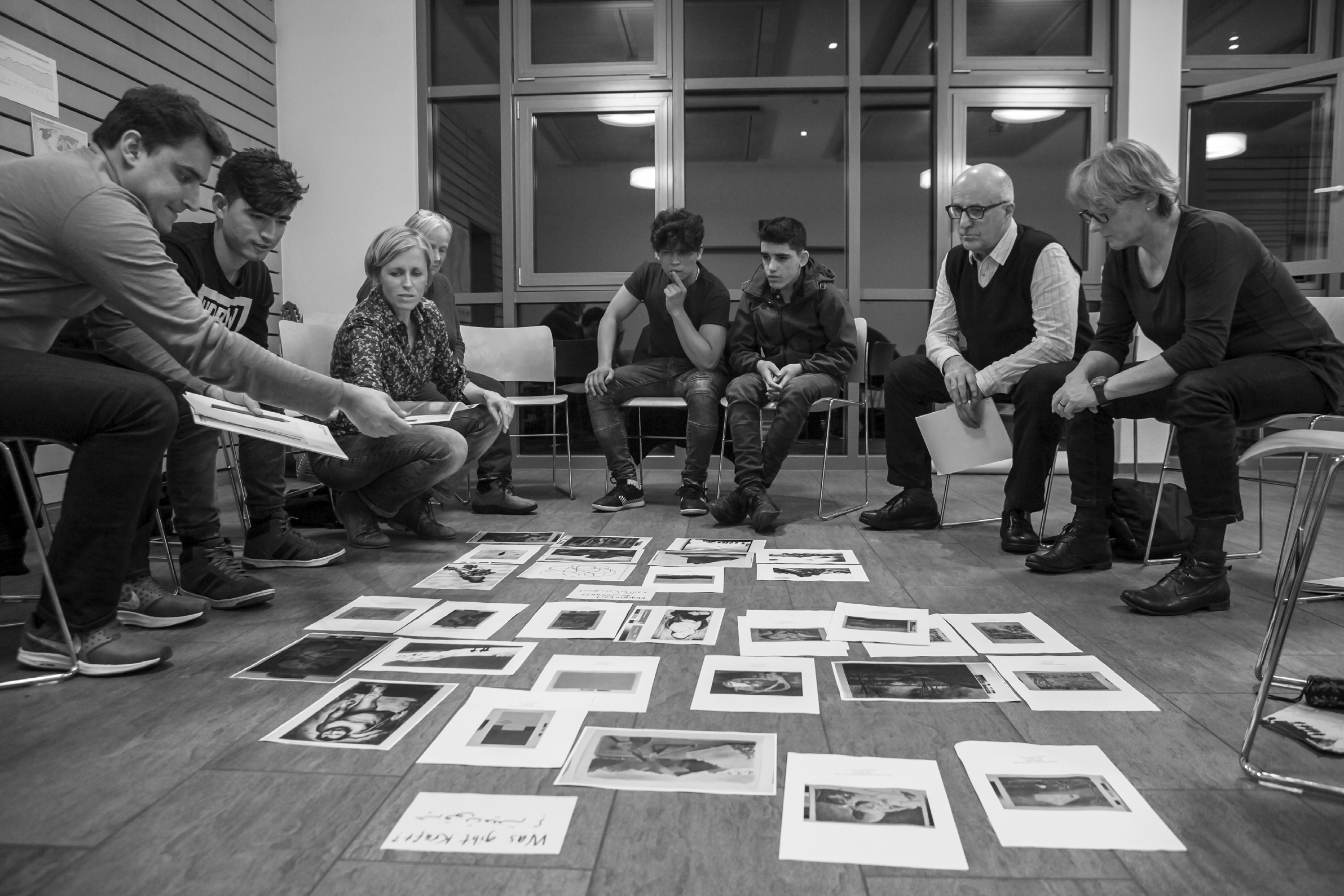

The group gathered a few times over several months, and viewed copies of works of art from the museum’s collection. Each person chose two, and was asked to say something about each one; the first why it reminded them of the place they came from, the second how it represented the situation they are in now.

The asylum seekers’ stories were quite moving – about leaving families behind and uncertain futures. But perhaps more incredible was the fact they could even tell these stories.

The asylum seekers and volunteers had first met when the parish church in Aeschi opened a welcome centre it named ‘Café International’, providing the men and women from central Asia and the Horn of Africa a place to meet, an introduction to Swiss culture and lessons in basic German.

However, beginner’s German wasn’t good enough to tell a story behind a painting, so Reinhard brought in interpreters.

“It was the first time in Switzerland that people worked with us,” says Golbedin, who explained that one of his chosen paintings showing two loggers at a sawmill in an alpine setting reflected his pleasure working with wood, being outside and how much he wants a job like that again.

Mohamed was drawn to a painting of a group of hikers, prominent in the foreground but in shadow, standing in awe of a glistening white peak towering above them. For an Afghan like Mohamed, mountains are inhospitable: “If someone is in the mountains it’s usually not a place to live,” he says.

“At the present moment I feel like I’m on a mountain and I’m looking for the future. I don’t know if I can stay here in Switzerland. I’m on the top of the mountain and I don’t know where to go, what to do.”

“I have children who are the same age. And that’s what I found so unsettling,” responds Verena, moved by the way the two Afghans were able to express themselves. “They’re here but don’t know what the future holds. I think of my children and how many opportunities they have.”

Christine related to the young men immediately, having experienced living abroad in India and Bangladesh as a young woman. “It’s stayed with me my entire life, the importance of having some friends with you to encourage you, even if you don’t have family or relatives nearby.”

The evening I meet the group could be the last time the four of them see each other. They’ve come to the café to hang some of the works of art they’ve talked about, and the public has been invited to see and hear about the results of the workshops, and say goodbye to the asylum seekers.

The authorities have decided to close the shelter and move the occupants elsewhere. This village, its surrounding green hills and steep mountain slopes, had reminded Golbedin and Mohamed of home, and now they were leaving.

“It’s an evergreen country,” says the 21-year-old Golbedin of the similarities, echoed by Mohamed, even if the two men come from different parts of Afghanistan – Golbedin from Kunduz in the northeast and Mohamed from Parwan province near Kabul.

“When I came here it felt as if I was at home because in our province, our village, we’ve got the same mountains and green places,” says Mohamed.

It’s Christine, a permanent resident, who doesn’t feel at home. The middle-aged Swiss woman moved to Aeschi about two decades ago. “It made me see that I’m not as integrated as I’d like to be. I have friends here but I wasn’t born here nor did I grow up here or have family or relatives here.

“I was looking for people who are close to me in spirit, and I found this. I realised how hard it can be to come to a new place and how important it is to open up a place where you can meet and make friends.” She realises her situation is very different to that of Golbedin and Mohamed, but says she can closely relate to their feelings.

Another picture that Golbedin chose to put up on the walls this evening is a painting of a blue-winged, red-breasted bird, perched on the end of a thin branch, ready to take wing.

“A bird lives like I do, changing its place according to the season. I don’t know if I can stay here or not. I had to leave Afghanistan. I’m not sure I can live here. Maybe I have to go somewhere else and start a new life,” he relates.

As the intimate event draws to a close, Golbedin takes the microphone while a countryman sits at the drums. I can’t understand what he’s singing but I interpret it like this: “We’re all strangers here, and strangely at home.”

Seeking asylum in Switzerland

At the time of the Aeschi exhibition, there were 65,000 people whose requests for asylum in Switzerland were being processed.

In the first quarter of 2018, reviews of 6,623 of these requests were completed, and 25% of the applicants were granted asylum.

According to the State Secretariat for Migration (SEM), requests can be rejected for any of the following reasons:

· Can return to a safe third country in which he or she was previously residing;

· Can travel to a third country that is responsible under an international agreement for conducting asylum and removal procedures;

· Can continue to a third country for which he or she holds a visa and where he or she can seek protection;

· Can continue to a third country where persons with whom he or she has a close relationship or dependants live;

· In particular if the application for asylum is made exclusively for economic or medical reasons.

Afghans are the second largest group of asylum seekers in Switzerland, behind Eritreans, accounting for about one in five of the total number.

(Source: SEMExternal link)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.