Caring for those who cannot afford health coverage

Readers wanted to know how a lower income affects a patient’s ability to access health care, and whether help is at hand in Switzerland and the United States to stop people from falling through the cracks.

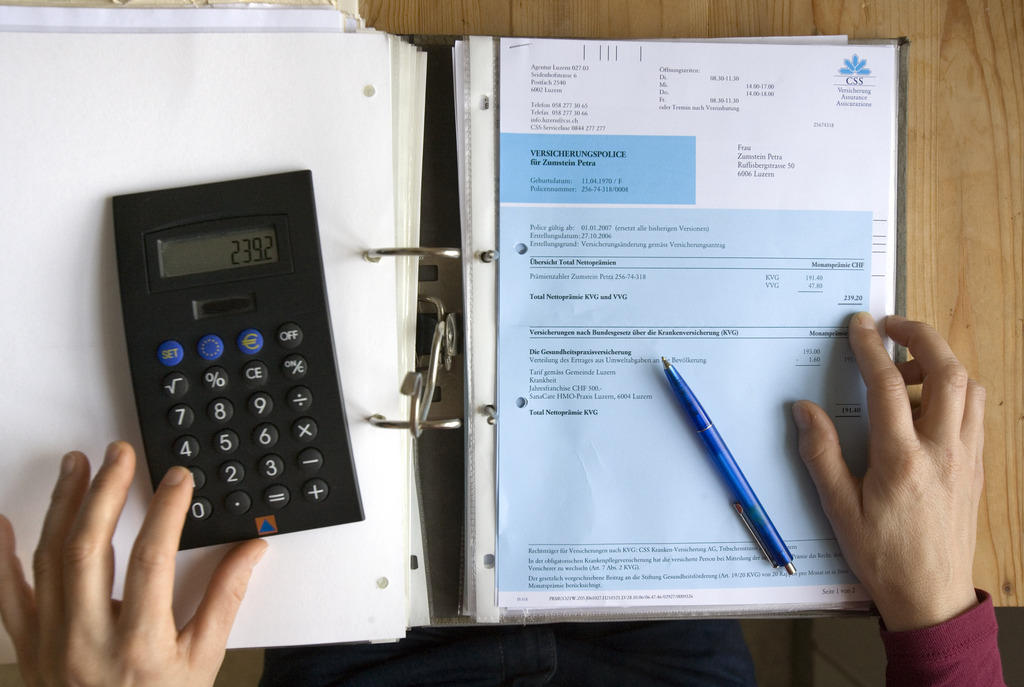

In Switzerland, people with modest means may struggle to pay for basic health coverage for two simple reasons: insurance premiums are not adjusted to income, and they have doubled in price since 1996, while salaries have risen by just one-fifth. It comes as no surprise, then, that just over a quarter of the population needed government assistanceExternal link to pay their premiums in 2014.

The state offers subsidies to ensure that everyone can afford basic health insurance, which is compulsory in Switzerland. Eligibility criteria is set by each canton. For households obtaining such assistance, insurance premiums account for 12% of disposable income, double the national average. Families, young adults and the elderly are the main subsidy recipients.

But this assistance does not reach everyone who needs it. People who fall just outside the income threshold for subsidies and those waiting as long as six months to receive their subsidies are at risk of marginalization, as one charity in Lausanne recently told swissinfo.ch. Debts owed to health insurance providers are a reality for more than half of the cases the charity sees.

Access to treatment

Even once people have managed to cover their insurance premiums, some still may have difficulty affording medical treatment. That’s because there are out-of-pocket expenses to contend with, in the form of deductibles before reimbursements kick in, and retention feesExternal link, or for services not covered by basic insurance.

To find savings, patients can lower their premium costsExternal link by switching providers (if they have no debts) or choosing a different policy, perhaps with a higher deductible. But some choose to take more drastic steps. A recent OECD report revealed that roughly one in fiveExternal link Swiss forego medical consultations because of cost, while one in 10 decide not to take prescribed medicines for the same reason.

Those paying the ultimate price, however, are the patients landing on so-called blacklists of people who have not paid their premiums, a move introduced in recent years by several cantons. Some 30,000 blacklisted patientsExternal link so far have lost their right to be reimbursed for medical services under basic insurance and can be refused care, save for emergencies. A policy initially designed to encourage people to pay up has instead come under fire for going against the principle of basic health coverage for allExternal link. If anyone is truly falling through the cracks, it may well be the blacklisted.

What about those struggling in the US?

Health care in the United States has prompted aggressively partisan debates about the role of governmentExternal link in social services, about costsExternal link, and even about taxesExternal link. Most skirmishes don’t include extended bipartisan recognition of the people who fall through the cracks of the American patchworkExternal link system, and the threads by which some of them are barely hanging on.

Even with implementation of the Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare, there are still 28 millionExternal link non-elderly uninsured people in the country. Although Obamacare expanded health coverage and assistance for millions of people, it doesn’t equate to universal coverage. Cost is a big reasonExternal link why people remain uninsured, and for some, a lack of legal immigration status prevents getting insurance. OthersExternal link without insurance faced a problem of making too much money to qualify for subsidies on the insurance exchanges, so they opt to roll the dice without insurance rather than pay full price.

A major group helped by the ACA are those too poor to have insurance through an employer plan or through the open market. MedicaidExternal link is the main public program available to help low-income or some disabled individuals (it covers 62 million people). A similar program called the Children’s Health Insurance Program, or CHIP, helps cover children. Part of the ACA allowed for states to expand Medicaid coverage, opening up Medicaid to people who weren’t initially eligible. But states weren’t forced to expand the program and could structure it to their preferences, which has led to a disparate systemExternal link.

So, a person’s likelihood of coverage and access to support could depend on where they live. And even within a state, there are inequities. For exampleExternal link, someone with access to an employer-sponsored health insurance option can’t fully utilize public assistance, even if their income is the same as someone who is eligible.

Poverty and health

But coming to the aid of people without an insurance lifeline means more than just having regular, direct access to health care. It also deals with the factors of everyday living that contribute to added stress, and worse health outcomes.

“Probably the worst pre-existing condition is poverty, and poor people that live in bad conditions don’t do very well,” J.B. SilversExternal link told meExternal link not long ago. The health finance professor at Case Western Reserve University said even if low-income people get to a hospital, they are discharged back into a neighborhood filled with hazards. They also face increased risks of expensive conditions like diabetes and heart disease, which has led to some effortsExternal link at linking health services to healthy behaviors. But overall, health care for the poor is seen as a reactive exercise in the United States, instead of a comprehensive piece of public service.

The Republicans have so far presented a number of proposals which aim at paring back the ACA’s impact and the costs of Medicaid. So far, these efforts haven’t succeeded, but should they return in similar form, they would likely shift more of the cost burden on to people who are most economically vulnerable.

As Silvers wrote in an articleExternal link this year, if politicians continue battling over specifics of the health care industry and not the overarching problems of access and coverage, “we could end up with a dysfunctional individual market and a much smaller Medicaid population with many more uninsured people”.

In other words, back to where the US started before its latest reforms.

Ask a question about the Swiss and US health care systems and we may cover it in this series:

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.