Lawsuits, drug coverage and antibiotics in the US and Switzerland

Our healthcare series answering reader questions about the US and Switzerland is coming to a close. Here, our journalists tackle some remaining questions about alternative medicines, malpractice, antibiotics and more.

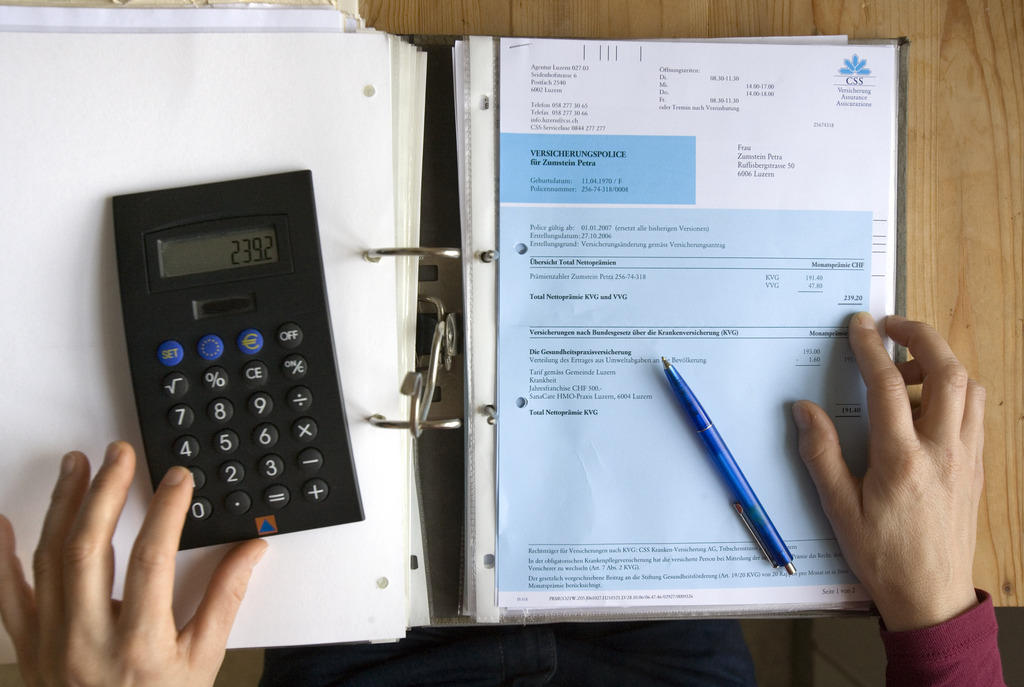

Does the Swiss health care system allow insurers to deny coverage for drugs or therapies prescribed by a doctor who believes such treatment is best for the patient?

Insurers are obliged to refund the cost of drugs prescribed by a doctor under basic health insurance, provided that these prescriptions or their components are included on constitutional listsExternal link maintained by the Federal Office of Public Health. To receive a full reimbursement, patients must take the medication for treatments designated in the lists.

For some medication, reimbursement is limited to a specified dosage. Your doctor must advise you if a drug is being prescribed for treatment other than the ones listed by the authorities, or whether the drug she’s prescribing is in fact covered by basic health insurance. Some drugs that don’t appear on these approved lists might be reimbursed only under complementary insurance, so it’s worth checking with your provider.

Health officials have also spelled out clearly which medical services, such as some preventive care measuresExternal link, lab testsExternal link, and maternal health servicesExternal link, are covered by compulsory basic insurance.

Is there a movement towards creating a single payer system in Switzerland, similar to the single payer movement in the US, which is supported by a majority of Americans?

It’s not for lack of trying that Switzerland has yet to replace the 60-odd private insurance providers with a single public institution to handle basic health insurance claims. Left-leaning parties and consumer advocates have put the proposal before voters three times in the last two decades, arguing the single payer model would bring down spiraling health costs. But the public rejected the idea fairly decisively – 70% of voters said no in 2007, 62% in 2014. During the last campaign, opponents warned against ballooning debts associated with state-run insurance systems like those in France or Austria.

But the tide of public opinion may be turning. According to a 2017 poll, more than two-thirds of SwissExternal link would now be in favour of a single payer system to reduce spending on health. The political will, however, just isn’t there – the federal government and most cantonal health ministers have traditionally campaigned against the single payer model, and opinion is divided about the best way to control costs. Switching to a single insurance provider would require a fundamental change to the current system. For now, it’s unclear whether the population and the government are really ready to take the plunge.

As for the US, it’s important to point out that although the majority referenced in the reader question about supporting a single-payer system has been shown in polls, that doesn’t make it a clear-cut mandate. Data from the Kaiser Family FoundationExternal link (KFF) still shows fiercely partisan divides on the issue of a single-payer insurer; 28% of polled Republicans support the idea, compared to 64% of Democrats.

KFF points out that the shift in overall majority acceptance for single-payer (53%) rests therefore on independents, of whom 55% support the idea. This seems to show that there is still very much a battle to win public opinion on what US healthcare should look like, though single-payer supporters have positive momentum in swing voters, at least those answering polls.

I believe one of the outrageous costs in the US system is the lawyers. What are per capita malpractice insurance costs?

An oft-mentioned source of inflated healthcare costs in the US is that of malpractice insurance and fear of lawsuits. Doctors are under immense pressure to treat patients, and the cost of a mistake or miscalculation can be serious. Patients who feel wronged can sue a medical professional, prompting more costs to insure against such claims, legal costs to fight them, etc.

And if we look at the numbers, the total cost does appear high. A Harvard study in 2010 estimatedExternal link ‘medical liability costs’ at $55.6 billion annually. But the details of that study also give some interesting insights. For starters, though it is a lot of money, it accounted for only 2.4% of annual healthcare spending; not enough to justify ballooning costs.

The study then broke down the numbers further, showing only $5.7 billion were linked to malpractice claim settlements, with another $4 billion in administrative/legal costs. The vast majority of the money spent ($45.6 billion) went on defensive medicine, or tests and procedures meant to help insulate a medical professional from lawsuits.

Data doesn’t seem External linkto show that malpractice lawsuits are on the rise, and areas like Texas which have capped some damage awards for malpractice cases haven’t really seen overall costs dip.

So, while the malpractice industry is costly, its reform is not the answer to a dramatic cut in healthcare costs. Still, as one commentator put itExternal link, studies of actual costs and actual savings show the “health care dilemma requires more than oversimplifications and political pontificating”.

On the other hand, Swiss malpractice law is much more specific, providing financial compensation only if a medical professional is found negligent.External link

Are complementary and alternative medicine covered by insurance in the US and Switzerland?

Since 2017, homeopathy, herbal medicine, holistic medicine, acupuncture and traditional Chinese medicine are covered by basic health insurance in Switzerland – provided they are administered by certified medical doctors.

The government’s decision to follow through on the results of a 2009 nationwide vote, in which two-thirds of Swiss approved placing alternative and complementary medicine on a par with conventional medicine for insurance coverage, led to consternation for some and jubilation for others, as swissinfo.ch reported at the time.

In the US this really is a case-by-case consideration. Some insurance may cover some alternative or complementary treatment options, but they aren’t required to do so. The Affordable Care Act did requireExternal link that insurers not discriminate against such treatments, but it doesn’t oblige insurers to bear the costs.

Given the rampant increase in antibiotic resistance, what are standard practices by health practitioners in the US and Switzerland in prescribing antibiotics?

According to Swiss health officials, the general rule of thumb for use of antibiotics is, “only if necessary”. Vague as this may sound, experts are working on developing concrete prescription guidelines as well as preventive measures to avoid the need for antibiotics, as part of a national Strategy on Antibiotic ResistanceExternal link that launched in 2015. Efforts are underway to guide not just health care practitioners, but also to inform the general public about antibiotic resistance.

In the US, medical professionals are also increasingly aware of the risks associated with over-prescribing antibiotics, or opting too early for powerful antibiotics in treatment plans. The US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) calls antibiotic resistanceExternal link one of the most urgent threats to public health, because antibiotics are a vital tool to treat certain bacterial infections; in some cases they can be life-saving.

But despite the ever-increasing awareness of judiciously employing antibiotics, the CDC says the US still can do more. A recent reviewExternal link showed outpatient treatment centers were prescribing up to 30% more antibiotics than necessary, while about 30% of antibiotics prescribed in hospitals probably weren’t necessary. Nursing homes were also key locations for antibiotics use, with 11% of residents taking them, and 40% being prescribed them without key information. And providers are turning more and more to high-power antibiotics

Overall, it seems US medical professionals are still working on implementing best practices to find a balance between the most effective treatments and the most prudent use of antibiotics.

Tony: We’ve covered an immense amount of material in this multi-month project. There are two big takeaways for me, and they apply in both countries, I think.

First, healthcare systems and costs are collections of things. Drug costs, subsidies, insurer structures, political will, and so much more all go into how much money we end up paying for care. There’s no silver bullet to lowering those costs, but we need to know that many things could contribute to less of a hit on your wallet.

Second, information and transparency are vital to making decisions on what a country wants its healthcare system to look like. Voters and consumers need to know how they spend their money, and how they could spend their money in a different way. They need to have information to know what the values are behind a system, like the Swiss decision to cover everyone. It was a choice of solidarity. That’s not to say that one decision, or collection of decisions, will be enough to make a healthcare system the best it can be. But a better-informed consumer and voter base will help to continue the reforms necessary to best suit a healthcare system for the present-day.

Geraldine: The true, hair-raising costs of the Swiss health care system should have been enough to make me ill, but it was the flu that finally did me in as we were preparing this final article. I can’t help but wonder if the antibiotics my doctor prescribed are doing me more harm than good.

Yet health care is a good deal about trust – trust in medical professionals who provide treatment, in pharmacists who offer advice, in public health officials who draw up national strategies, in social security systems that can catch you when you hit hard times and can no longer pay your health insurance. But we also put our trust in our fellow citizens, because health care is a collective responsibility.

Tony is right: The more we all know about the basic functioning of our system, the better our chances of finding solutions for reforming what are undoubtedly two unsustainably expensive and imperfect health care systems. Now pass me those meds.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.