‘We need a global vision of sustainability’

The issue of palm oil will loom large when Swiss go to the polls on March 7 to vote on a proposed free trade agreement with Indonesia. Referendum initiator Willy Cretegny says however that the stakes are even bigger: the entire concept of free trade is based solely on profit – to the detriment of resource management, he argues.

The deal, which has already been formally ratified, aims to ease Swiss exports to Indonesia by removing almost all customs duties and certain technical obstacles to trade. Duties will be abolished on industrial goods and certain agricultural products coming into Switzerland, including palm oil, of which Indonesia is the world’s biggest exporter.

More

Indonesia’s palm oil angers Swiss anti-globalisation activists

The agreement includes a specific article on sustainable development wherein both parties pledge to protect the environment and to respect human rights and the rights of workers. This article also specifies that palm oil will only be eligible for reduced customs duties if it is produced sustainably.

Willy Cretegny initiated the referendum to challenge this agreement, helped by the Swiss Ecologist Party and the youth wings of the Green and Social Democrat parties. For this organic winegrower from Geneva, the entire global trading system needs to be called into question.

Website of the referendum initiatorsExternal link

Website of the committee supporting the trade dealExternal link

The complete text of the agreement signed with IndonesiaExternal link

An overview by the State Secretary of Economic AffairsExternal link

The government website on the three issues to be put to the vote on March 7External link

SWI swissinfo.ch: What bothers you about the concept of free trade?

Willy Cretegny: Free trade aims to reduce or abolish all tariffs and non-tariff measures, which are extremely important for fair trade and to avoid distorting competition. Duties help to rebalance prices between one economy and another and have a crucial impact on the major problem of over-consumption. With free trade, we have access to a vast array of goods at prices that have nothing to do with our purchasing power, so we consume more and more. And the distortion of competition means entire sectors of local economies disappear, here or elsewhere.

I often quote the example of IKEA, which produces most of its low-cost furniture in Asia, then imports it to Europe and Switzerland almost duty-free, and finally sells it at very low prices, thereby destroying most of the furniture manufacturers in our region. IKEA’s employees are paid according to collective agreements, but the salaries aren’t high enough to avoid turning to state welfare payments to help with housing and health insurance costs. Meanwhile, the family that owns the company is one of the wealthiest in Switzerland. By abolishing tariffs, free trade becomes a tool to drain public finances.

SWI: What do you propose instead?

W.C.: I advocate win-win trade agreements for exporting and importing countries, so that all local economies can continue to function. I propose that we simply recognise the importance of tariffs and non-tariff measures.

Some call this protectionism, but to me it’s a policy of openness, because it’s based on a respect for the choices of each country – in contrast to the WTO and free trade agreements, which are focussed purely on the growth of trade and profits. At present we are levelling the playing-field and standardising, and in the process we are developing a system extremely harmful to the planet in terms of the environment, pollution and over-consumption.

Switzerland should set an example. Of course, we can’t change our behaviour from one day to the next because we are already committed to several agreements. But we should issue Swiss negotiators a different mandate, so that treaties take social and environmental issues into account and become geared towards respecting local contexts.

SWI: You believe that the sustainability criteria in the free trade agreement with Indonesia are inadequate. Why?

W.C.: The parties have agreed not to use arbitration in the event of a dispute concerning Chapter 8 of the agreement, which deals with sustainable development. This suggests that they consider those aspects to be of little importance, or at least not important enough to get in the way of other terms of the treaty. So it’s a sustainability standard with few guarantees.

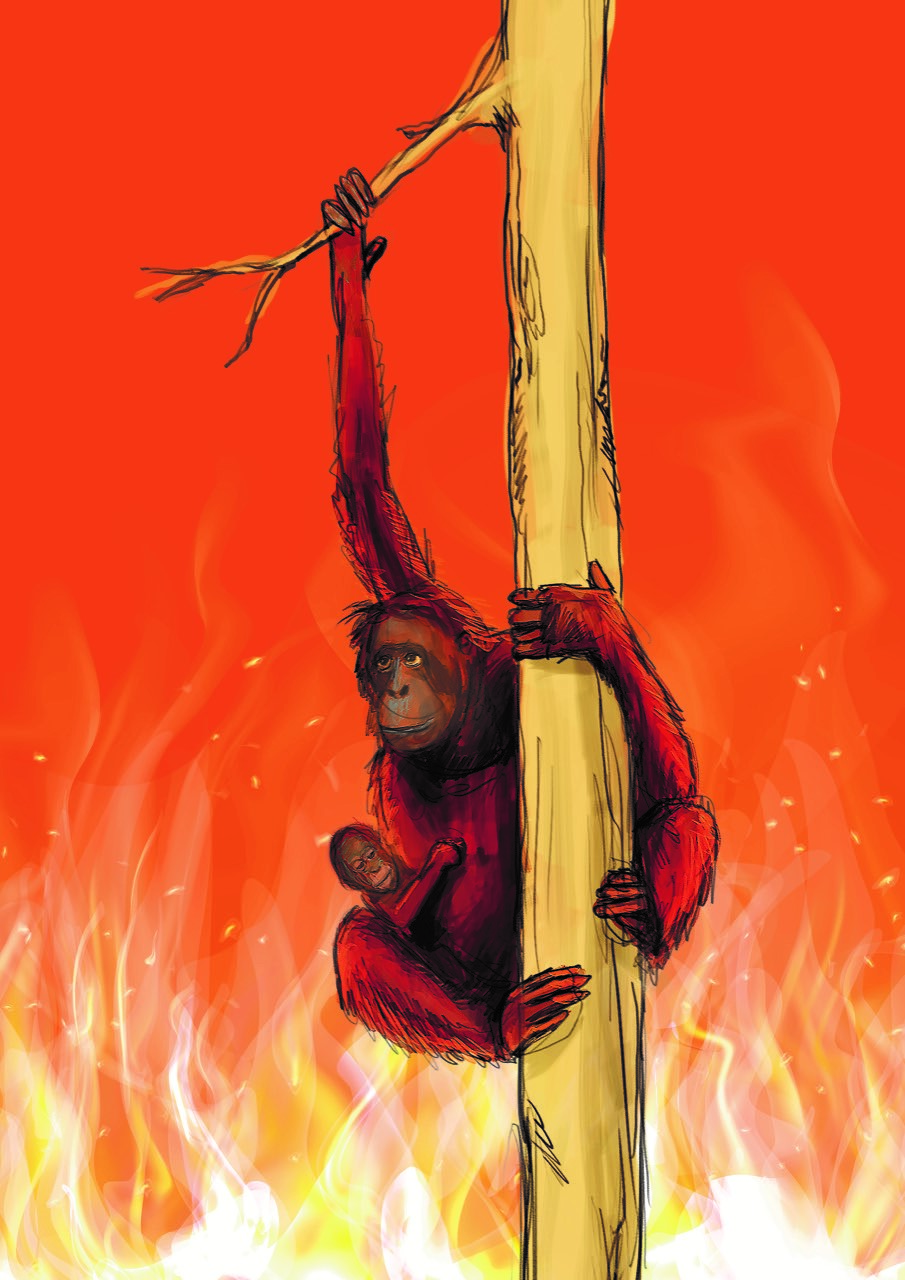

SWI: You state in your argument that there is no such thing as sustainable palm oil. How so?

W.C.: Indonesia has adopted a widespread policy of deforestation in recent years to grow this product for export. Even when it is certified as organic, palm oil is often a result of the disappearance of a part of the rainforest.

Plus, importing palm oil to Switzerland means transporting a commodity from the other side of the planet, which isn’t sustainable. Especially since we can meet part of our needs with local vegetable oils like rapeseed and sunflower, and the rest with oils imported from Europe, like olive oil.

More

‘This agreement lays the foundation for a more sustainable and fairer economy’

SWI: Isn’t this article on sustainability in the free trade agreement a first step towards more environmentally friendly production in Indonesia?

W.C.: It makes sense to promote sustainable agriculture in Indonesia, but not to make palm oil in Indonesia for export to Switzerland or European countries. We need a global vision of sustainability.

In food production today, almost all our oil needs are met by palm oil, and the only impetus for that has been financial interests since this product costs next to nothing. That’s the main drawback of free trade: the rationale is no longer resource management; it is solely profit and the market.

SWI: This agreement with Indonesia also allows Swiss companies to export their products at better conditions. Don’t you want to support the Swiss economy?

W.C.: I don’t want to support a destructive economy. Free trade practices draw all countries into a competition – a race to gain advantage. If we traded with tariffs and non-tariff measures, products and services would be chosen on the basis of quality and not just price.

I completely understand that national exporters and producers are struggling due to global price pressures. But it’s not sustainable – we have to sacrifice everything just to survive.

I am a defender of the economy, but also of an economy that has margins and guarantees that businesses and jobs can be sustained. We are currently in the process of undermining the local economy, and we are increasingly competing against huge corporations. And we are losing control.

More

Can commodity traders get a grip on their soy supply chains?

SWI: How do you explain the fact that some associations committed to protecting the environment, such as Public Eye and Greenpeace, don’t back you?

W.C.: According to our information, their reasons for not supporting our initiative are purely political. The World Wildlife Fund, for example, is a partner in certification bodies. These groups also have local chapters and fear for their future on the ground there.

Unfortunately, these associations are happy to include sustainability in an agreement even if it offers few guarantees. They have not understood that it’s the principle of free trade and its policy of destruction that must be re-evaluated.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!