When the Middle East was reinvented in Switzerland

The 1923 Lausanne Peace Treaty defined countries and drew borders. Its goal was to pacify the Middle East. An exhibition at the Lausanne History Museum shows why this failed.

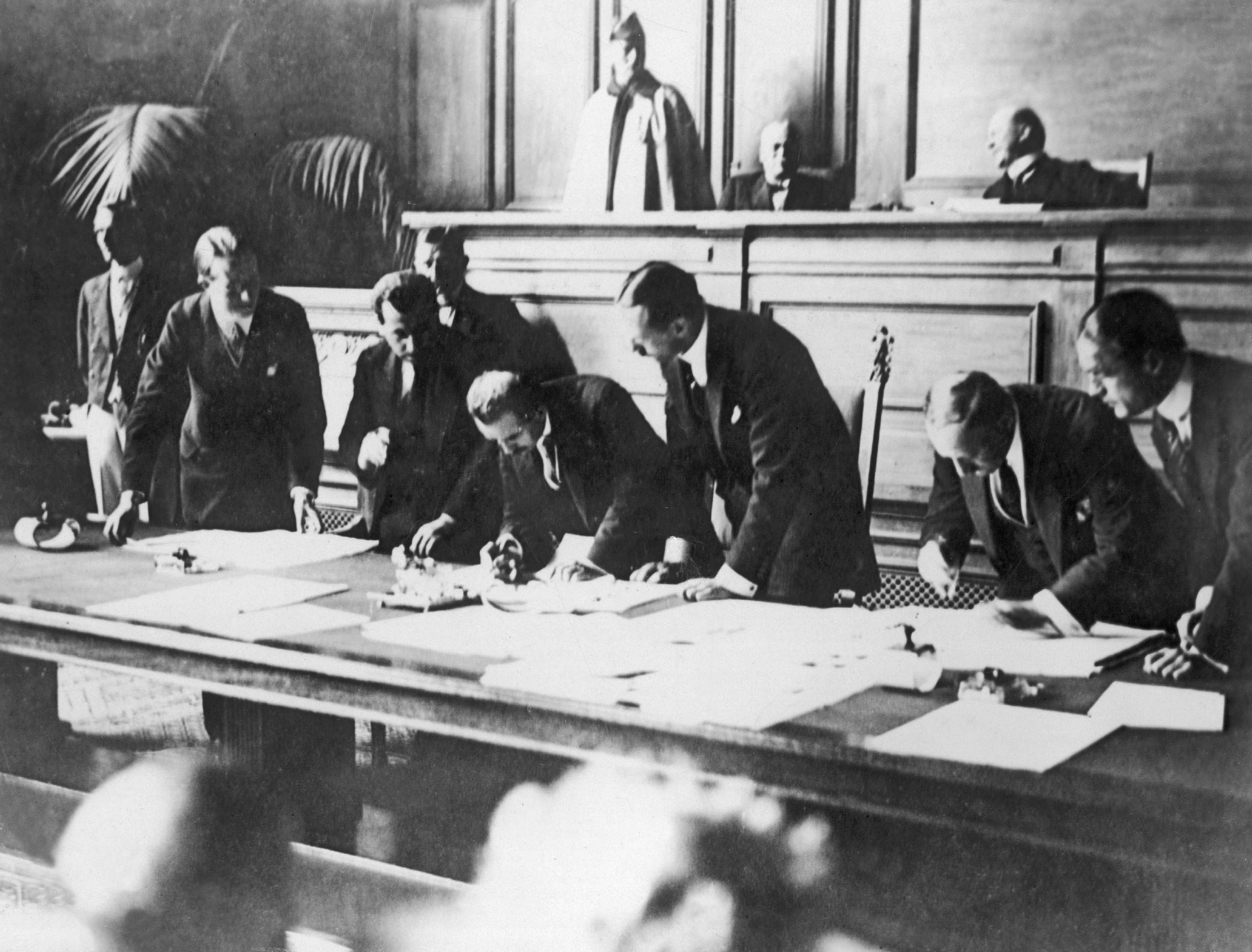

It is an illustrious crowd of guests that arrives in Lausanne in November 1922: kings, presidents, ministers and personalities from business and politics. The First World War officially ended a few years ago, but conflicts continue to smoulder – especially on the south-eastern edge of Europe, in what is now Turkey.

The goal of the conference, which will drag on for the next eight months: to develop a peace plan for the Middle East, as ethnologist and co-curator of the exhibition “Frontières. Le Traité de Lausanne 1923 – 2023”, Gaby Fierz, explains: “The Treaty of Lausanne, signed in July 1923, definitively defined the borders in the territory of the former Ottoman Empire, i.e. those of Turkey, Greece, Syria and Iraq.”

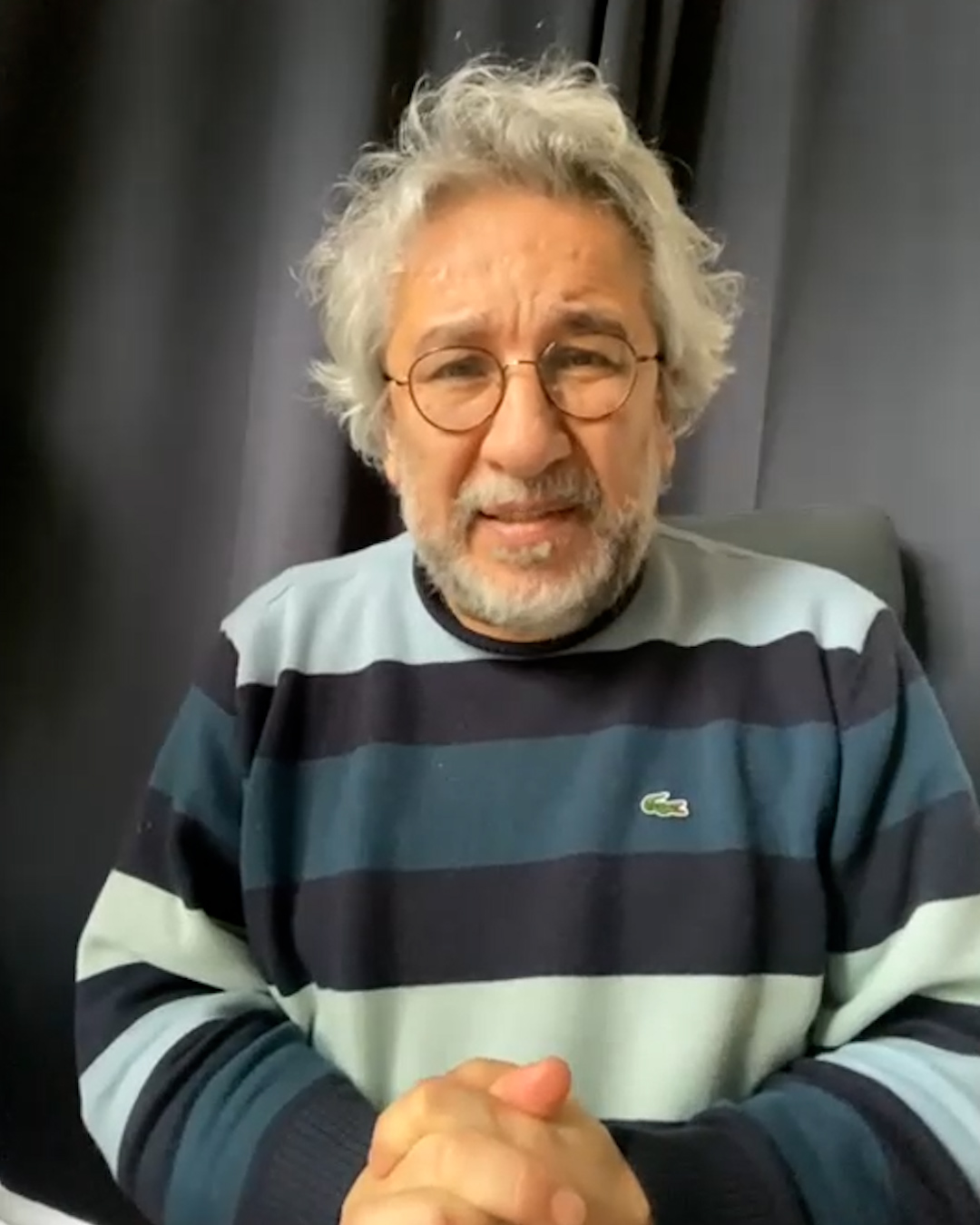

“Lausanne has enormous significance for Turkey,” says journalist Çiğdem Akyol, author of the book The Divided Republic: “Practically every Turk knows the date July 24 by heart.”

Lausanne – a late victory for young Turkey

And “Lausanne” was a late victory for Turkey. For in 1920, only three years earlier, the victorious powers of the First World War had a completely different plan. According to the Treaty of Sèvres, large parts of the former Ottoman Empire were to be ceded to France, Great Britain and Greece. In the east, an independent Armenia would be created, and the Kurds were promised their own state.

“The victorious powers of the First World War – led by France and the British Empire – together with the Ottoman Empire decided on the dismemberment of the former multi-ethnic state,” explains Akyol: “The new state shrank to Anatolia west of the Euphrates”, while the Dardanelles remained under the control of the Allies. Around 80% of the territory was lost in the process. Naturally, this treaty met with little approval in Turkey.

The treaty was not signed. In Turkey, the remaining remnant of a former world empire, a power struggle had been raging since the beginning of the 20th century between the Sultan and his entourage on the one hand and a secular movement, the so-called Young Turks, on the other.

At the time of the treaty negotiations in Sèvres, there were already two governments: one in Istanbul and one in Ankara. When the results were finally in, the nationalists accused Sultan Mehmed VI of treason, gained power and did not sign the Treaty of Sèvres.

Greek-Turkish War

Besides, the Greeks were also there. Driven by the idea of creating a Greater Greece, Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos had Greek troops march into Anatolia in May 1919. The aim was to annex at least the city of Smyrna – today’s Izmir. But the real goal was the conquest of Constantinople.

But Mustafa Kemal put a spoke in the Greeks’ wheel. After months of fighting in western Anatolia, Kemal’s troops were able to put the Greeks to flight at the Battle of Dumlupinar.

The outcome of the Greek-Turkish war was devastating. Tens of thousands of soldiers died. Moreover, both armies pursued a scorched earth policy. The civilian population was declared the enemy and was raped, tortured and killed. Towns and villages were burned to the ground. Finally, in September 1922, Smyrna was conquered – the city occupied by Greece in 1919 and placed under Greek sovereignty in the Treaty of Sèvres.

Who lit the fires that destroyed the Greek and Armenian quarters of Smyrna is disputed among experts. The fact is that a large part of the former population of this multi-religious, multi-ethnic city perished in the flames or was driven out by the advancing Turkish troops. Pictures from that time show tens of thousands of people crowding together on the quays of the city to escape the flames.

Two big losers

The situation at the end of 1922 was thus completely different from three years earlier, when the first peace treaty had been negotiated in Sèvres near Paris. “The Turks now came to Lausanne as the victorious power and were treated as such,” says Gaby Fierz.

This was quite in contrast to the Armenians, who were present in Lausanne but not listened to: “When the Armenian delegation appeared before the commission dealing with the question of minorities, the Turks left the room in protest,” Fierz says.

Meanwhile the Kurds were not represented as an independent delegation. “They were virtually subsumed under the Turks, a representation they naturally rejected. In the end, they were scattered among four states.”

A treaty with consequences to this day

This is still the case today. Kurds are considered the world’s largest people without their own national territory. Only in northern Iraq have they enjoyed a certain degree of autonomy since the 1970s. Armenia was also left empty-handed. A small part of the settlement area was assigned to the USSR, the larger part to Turkey.

The Treaty of Lausanne represents Turkey’s return to the international stage, says Akyol: “But this treaty did not only mean peace. It was also the beginning of expulsions and forced deportations and led to millions of people losing their homes,” she explains, referring to the agreement on “compulsory population exchange” also signed in Lausanne.

Displaced, resettled, uprooted

Greeks from Anatolia were “exchanged” with Turks from Greece because of their religious affiliation. The vast majority of them had lived in the respective countries for generations and also spoke the language and not the language of the country to which they were now being deported. “This was not an exchange, but a forced expulsion,” says Fierz.

It also had to do with the prevailing doctrine at the time: “One religion, one language, one state.” That was the concept of the nation state as it was conceived in the 19th century, says Fierz, “an antithesis to the multi-ethnic Ottoman Empire. But it was rigorously enforced.”

Around 1.5 million people – the exact numbers are disputed here as well – were “exchanged” in a few months at that time and encountered a local population that was neither prepared for nor enthusiastic about it.

Instrumentalisation of a historical date

It is interesting to note that even the big winner of that time, Turkey, has a different view of the Treaty of Lausanne today. When President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan celebrated the conversion of the famous former museum Hagia Sophia into a mosque in 2020, he did so on July 24, the date of the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne.

This was a slap in the face for the supporters of a secular Turkey, says Akyol: “For Kemalists and seculars, the Treaty of Lausanne was a victory over Europe.” For the Islamic conservatives, on the other hand, who have been in power for 20 years, it was primarily associated with a loss of territory and the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire.

The Treaty of Lausanne – signed 100 years ago – redrew borders and defined countries, but in the process it also left some questions unanswered, divided families and forced millions to flee. And it did not achieve its goal – to bring peace to the Middle East.

The exhibition “Frontières. Le Traité de Lausanne, 1923-2023External link” runs from April 27 to 8 October 8, 2023 at the Lausanne History Museum.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.