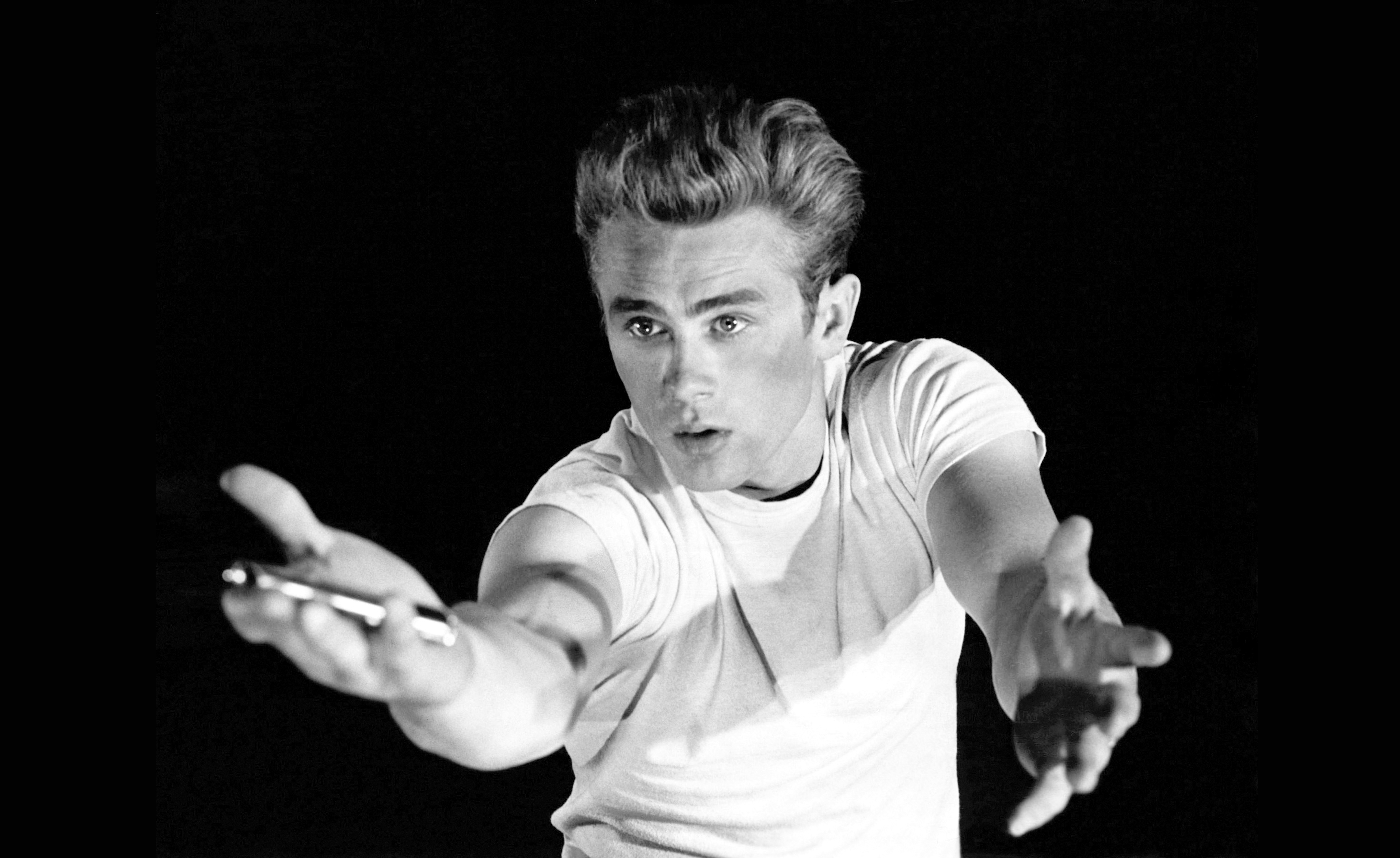

Whiter than white: how spotless is your T-shirt?

Swiss clothing company Switcher is regarded as an example to follow for the world textile industry. Its T-shirts are produced with respect for the people who make them and with a reduced environmental impact. Yet the fair-trade model has its limits.

Wash day for the average person means lots of socks and trousers – and T-shirts. “Made in Bangladesh”, “made in China”, “made in Thailand”, say the labels. What a relief to get them all clean. But a nagging question remains: how cleanly were they produced?

According to Géraldine Viret, spokeswoman of the NGO Berne Declaration, “the consumer has no real guarantee that a T-shirt was produced with respect for the rights of workers”.

The Swiss NGO, which is a part of the Clean Clothes Campaign, an international coalition to improve working conditions in the clothing industry, points out that “most textile companies do not pay decent wages”.

Among the exceptions is the Swiss company Switcher, often cited as a model for others to follow. swissinfo.ch visited its headquarters at Le Mont, near Lausanne, to find out how the company goes about producing T-shirts in a socially responsible manner.

More

New owners for old shirts

Avoiding harmful chemicals

Just like its very open premises, the brand of T-shirts launched in 1981 emphasises transparency. The philosophy of Switcher is clear.

“Anyone who wants to work with us has to sign up to our code of conduct. It does not matter if the company is in Bangladesh, Turkey or Switzerland. We apply strict criteria along the whole chain of production,” explains Gilles Dana, who for 15 years has been responsible for sustainable development at Switcher.

The material most used in making Switcher’s T-shirts – cotton – comes mainly from cooperatives in China, India and Turkey. A basic price is guaranteed to farmers who produce organically, and they get an extra allowance to invest in community projects like schools or wells.

The initial phases of working cotton, from spinning to weaving, are almost all automated. The social aspect is less relevant here, Dana notes. What is problematic is the use of chemicals to whiten, colour, soften or fireproof the material.

“Working a kilo of cotton or synthetic material generally requires 500 to 1,500 grammes of chemicals,” said Peter Waeber, manager of bluesign, a Swiss company specialising in environmental certification for the textile industry.

Doing without chemicals altogether is a bit of a problem, as Dana knows. To reduce environmental and health impacts, Switcher conforms to the Oekotex standards, which exclude use of the more harmful substances. They also try to batch their orders as much as possible.

“It works like a washing machine: you wait till it’s full to start it up, rather than running it for every single item,” he says.

The critical stage, he explains, starts when the material goes to the textile manufacturer. Here is where most of the textile workers are – 30 million people worldwide – and it is where working conditions can be a major cause of concern.

Solidarity fund

The fact that many companies only pay the legal minimum wage is shameful, says the Berne Declaration. In the textile industry, the workers get the smallest slice out of the price of a T-shirt.

More

The price of a T-shirt

“As part of the Clean Clothes Campaign we are calling for payment of a living wage which covers basic needs like housing, transport, medicines and schooling,” says Viret, adding that only those who are members of the Fair Wear Foundation, the organisation certifying these higher standards, commit to paying decent salaries.

As the first Swiss company to join Fair Wear, Switcher ensures living wages through a special programme. “Given a minimum wage of $68 (CHF62) a month, a seamstress in Bangladesh earns between five and seven cents a T-shirt. We are committed to paying three cents extra for every garment,” Dana said.

Once a year, this solidarity fund is distributed to all workers in the factory, including those who did not work on Switcher T-shirts.

“At the end, we have maybe $10,000 for 3,500 workers. Sure, it’s not a lot, because we are not a big customer. But if other brands did the same, pay would double,” he says.

Audits carried out in textile factories by independent agencies are often scheduled in advance, with notice of a month or two, explains Gilles Dana of Switcher. “Being put on notice like that is often enough to make the factory owners invest in improvements”, he says, while admitting that the system has its downside.

Hiding malfunctions or producing bogus pay certificates can be easy enough to do, especially in countries where there is a lot of corruption. “The expert inspector who works for a recognised company is still in a position to identify the more serious problems”, he maintains.

Asked about this by swissinfo.ch, the Fair Wear Foundation said it “always announces factory audits in advance because we find that managers are generally more open to collaboration and workplace improvements if audits are announced. Pre-planning audits also ensures that appropriate managers and documents are accessible on the days of the audit”.

According to NGO Berne Declaration, however, scheduled inspections are not the ideal solution. In Bangladesh, it points out, the question of inspections is just one of the problems. The state of repair of buildings has never been seriously examined and there has been no move to make the needed renovations.

Besides audits, Berne Declaration insists, there is a need for other measures, such as interviews with workers away from the factory, discussions with trade unions and NGOs on the ground, as well as audits at the headquarters of the brands to determine the real extent to which social responsibility translates into purchasing policies.

Traceability code

To belong to Fair Wear means having compulsory inspections in factories and offices. “All our suppliers have to submit to checks. The same goes for us,” he adds.

Last year, almost half of the 24 Switcher suppliers were inspected. “We found that one company had sub-contracted our order. We cancelled the contract right away,” says Dana, emphasising that traceability of products is one of Switcher’s basic principles.

All their T-shirts (2.5 million in 2012) are labelled with a code (the “respect code”) which indicates where they come from and who manufactured them.

Limits of fair trade

Traceability, like fair-trade production in general, has its limits, as people working in the industry admit.

For garments made up of several pieces – like jackets and bras – ensuring traceability is well-nigh impossible. The Switcher model, Dana notes, works best for a small company that uses a limited number of suppliers.

Switcher, like some other companies, does incredible work, says Peter Waeber of bluesign. “But don’t forget that growing cotton takes a lot of water and contributes to soil erosion. There is no such thing as being 100% environment-friendly.”

Switcher does not just use organic cotton. On the contrary, two-thirds of its cotton come from conventional cultivation – “for economic reasons”, according to Dana.

These are the same reasons that have prompted Switcher to move its production bit by bit from Asia to southern Europe. “We have to turn a profit. We’re still a business, not an NGO.”

On April 23, 2013, the collapse of Rana Plaza at Dhaka, in Bangladesh, caused 1,200 deaths. The eight-storey building, designed for five storeys, accommodated textile businesses supplying European and American brands. Called by some the “9/11 of the textile industry”, the Rana Plaza disaster was the most tragic event in the history of this industry in Bangladesh.

Nine months later, workers’ families are still waiting for compensation, notes Berne Declaration. “The positive aspect here has been the increasing involvement of companies in the Agreement on Building Safety in Bangladesh, a legally binding accord which involves independent inspections. The companies have to contribute to the costs of improvements.”

120 brands have signed up to the agreement so far. In an interview with the Tages-Anzeiger newspaper (January 22, 2014), Philip Jennings, secretary-general of UNI Global Union, a global trade union federation for skills and services, expressed concern at the refusal of some companies – including the Swiss retail giants Migros and Coop – to join the agreement.

The newspaper said Migros and Coop justify their position by saying that the financial implications are not clear.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.