Why Nestlé’s millions to protect an African forest could backfire

The Swiss multinational’s commitment to invest millions in protecting a part of Ivory Coast from cocoa-related deforestation could do more harm than good if the money isn’t spent wisely.

The West African country of Ivory Coast has sacrificed a lot to become the world’s largest producer of cocoa.

“It has lost around 94% of its forests since independence,” says Etelle Higonnet of the US-based environmental NGO Mighty Earth, which tracks deforestation from the cocoa industry. In 2018, the country was second only to Ghana in terms of the intensity and speed with which it cleared its forests.

According to Higonnet, around 200 of the 244 forest reserves and national parks in Ivory Coast are more than 90% destroyed and exist only on paper. She estimates that cocoa cultivation alone is responsible for a third of all deforestation in the country and shoulders up to 90% of the blame for destroyed forest reserves – known as “Forêt Classée” in French-speaking West Africa – and national parks.

“This has created a situation where around 30% of Ivorian cocoa is illegal,” she says.

Cocoa has been grown illegally in many forest reserves for decades, and it is not feasible to evacuate hundreds of thousands of people who have settled in these areas. This presents a problem for chocolate producers like Nestlé that have made zero-deforestation commitments in the face of criticism for contributing to climate change. They rely on cocoa from Ivory Coast, but increasingly cannot avoid sourcing it from the numerous areas that have been cleared of forests.

A new policy of the Ivorian government intends to change the forest classification to reflect on-the-ground realities. Intact forest reserves and national parks will be fully protected while highly degraded ones will be reclassified as agroforestry concessions where formerly illegal cocoa production will be optimised with help from international chocolate companies.

Cavally to the rescue

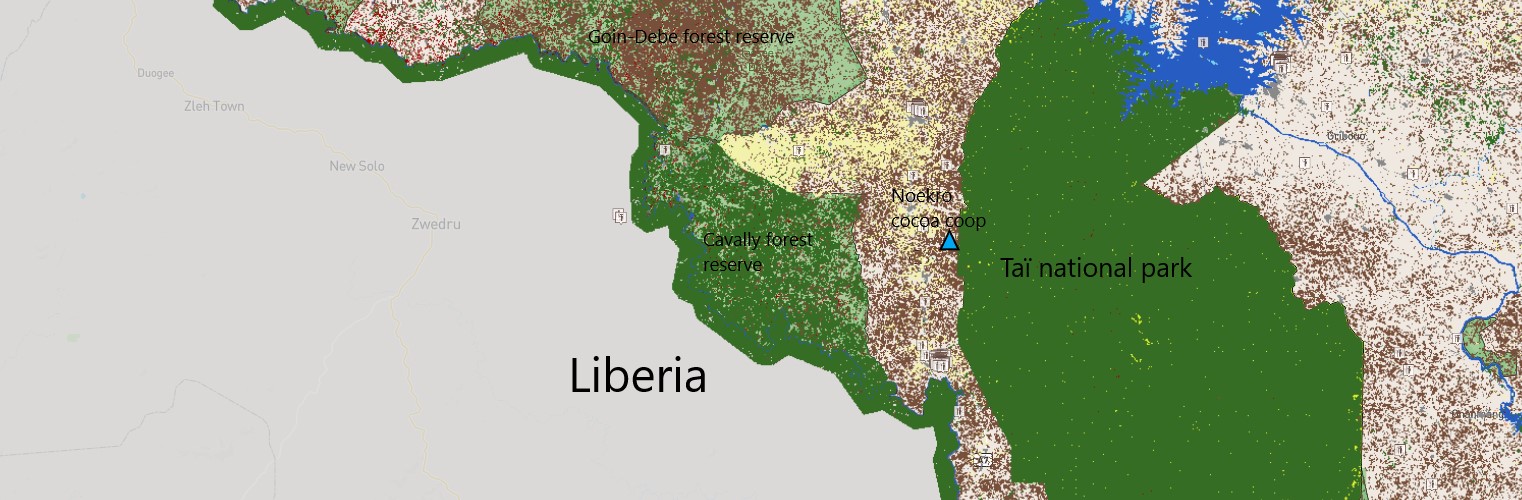

So, Nestlé has turned its attention to reducing cocoa-linked deforestation in Ivory Coast’s relatively intact forests. This has the added benefit of potentially helping the multinational meet its commitment of zero net carbon emissions by 2050. Last month the Swiss company announcedExternal link that it was investing CHF2.5 million ($2.75 million) over the next three years to help protect the 67,500-hectare Cavally forest reserve – which is a third the size of the economic capital of Abidjan in area.

“Cavally is one of the best-preserved forest reserves because it is in the southwest of the country. Cocoa production in the country started off in the east and migrated to the southwest as growers searched for more fertile land,” says Renzo Verne of the Earthworm Foundation that will help Nestlé implement the project.

The reserve is also strategically important as it forms a natural forest corridor into Liberia whose forests are in relatively good health due to lack of development there. Nestlé’s closest cocoa supplier to Cavally is a cooperative in the town of Noekro, around 15 kilometres to the east (almost on the border of neighbouring Taï national park).

Cavally is pockmarked with several small deforested patches, for which cocoa cultivation is largely responsible. Satellite imaging done between 2017 and 2018 for Ivory Coast’s forest department with state-of-the-art Airbus Starling technology revealed that 58% of the forest reserve is still intact, 33% severely degraded and 7% partially degraded.

“Cavally is under threat and there has been encroachment in recent years linked to the cocoa industry which needs to stop,” says Verne. .

Nestlé has drawn up a high-level plan for intervention in Cavally with five key goals: Reduce the level of deforestation; work with local communities to identify ways to help protect the reserve; rehabilitate degraded areas via tree planting and protection together with the community; identify and promote resilient agricultural practices for those communities living in the periphery of the forest; and identify innovative learnings that are replicable in Ivory Coast’s other protected forests.

Perverse incentive?

On request, Nestlé declined to share details about how the CHF2.5 million will be distributed among the five goals. According to Verne, most of the funds will go towards replanting work and improving living conditions for communities living outside the forest so that they are not tempted to take up illegal cocoa production. Another resource-intensive intervention is finding alternative livelihoods for people growing cocoa illegally in the forest.

“We have to understand that these people are simply looking to improve their lives and the chocolate industry also wants cocoa,” says Verne. “Many of them are coming from a difficult situation and a lot of them are not Ivorian nationals but come from Burkina Faso. We want to find alternative economic solutions for these people by working with farmers, communities, and the government.”

But Emmanuelle Normand of the Swiss-based Wild Chimpanzee Foundation, who has been working in the Cavally area since 2002, is completely against the idea of compensating those cultivating cocoa illegally in the forest reserve.

“They are recent arrivals and hence should be evicted without compensation or they will later claim rights to the forest,” she says.

According to Normand, encroachment into Cavally began in 2011- after Ivory Coast’s second civil war. Demobilised soldiers of the victorious president-elect Alassane Ouattara began selling fake land titles to cocoa cultivators from outside the region. In 2017, thanks to awareness raised by the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation, some 7,000 encroachers left the forest reserve. Half of them went to Burkina Faso and the other half found work on cocoa farms around Cavally. However, ex-militia members recently succeeded in convincing another batch of outsiders to part with their money in return for fake land titles.

“There are no settlements inside Cavally and the people cultivating cocoa in the forest reserve should be evicted by patrols,” argues Normand.

Verne is aware of the complexity of the situation. To further understand what is going on in Cavally, the Earthworm Foundation plans to first do a survey to find out the socio-economic reality of the people living in the forest. However, giving people financial incentives to take part in a census or survey could encourage more people to enter the forest reserve and be counter-productive, Normand warns.

“If they want to identify people cultivating cocoa in Cavally with a view to compensating them, it will destroy the forest.”

Her team experienced this first-hand in Marahoué national park, another area in Ivory Coast affected by deforestation. According to Normand, a lot of people came into the park to be identified and receive compensation when it was announced that there was going to be a survey of people living there.

So what should Nestlé’s money go towards?

“Invest in law enforcement inside the reserve and do not try to compensate those inside,” Normand urges. “If we manage to make people abandon cocoa cultivation inside [the reserve], then natural forest regeneration will happen automatically and successfully.”

More

Why little Switzerland matters for the survival of tropical forests

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.