Can deep geothermal projects help secure Swiss energy independence?

The war in Ukraine and the climate crisis have governments working to source more energy locally. Advocates for geothermal energy say it can help Switzerland do so but a “success story” is needed.

At the luxurious thermal baths of Lavey-les-BainsExternal link, visitors can be found wallowing in outdoor pools admiring white mountain peaks in the distance.

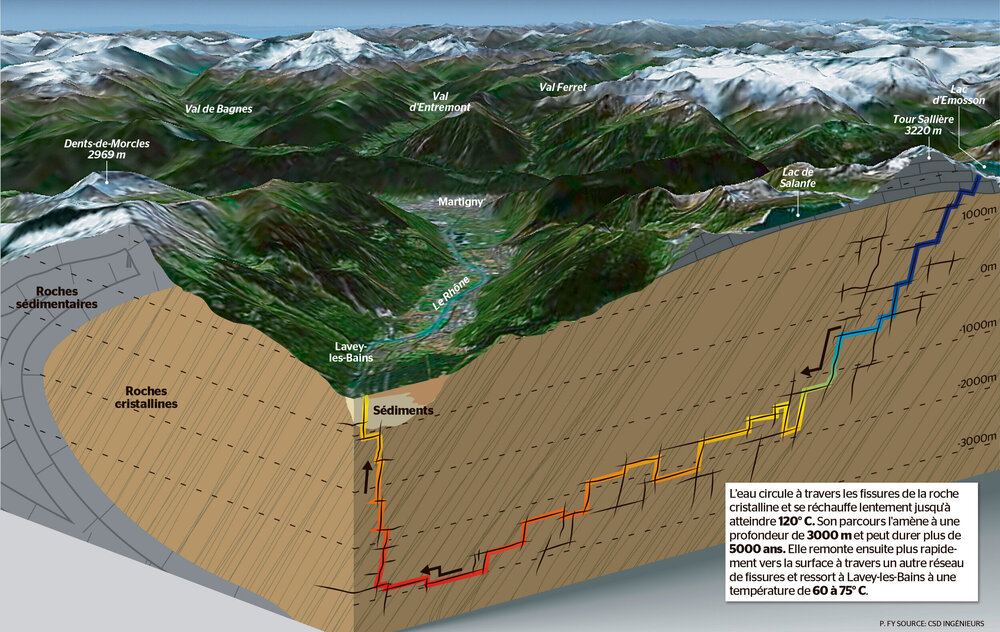

At 33-36 degrees Celsius, the therapeutic bubbling water is supposedly the hottest in Switzerland. When it emerges in the Rhone Valley not far from Lake Geneva, the water has already been on a long meandering journey. From the mountains opposite, it flows underground to a depth of 3,000 metres, heating up before rising quickly to the surface at the village of Lavey-Morcles via a network of cracks.

Just a stone’s throw from the baths, a clanking drilling rig shatters the silence. Since January, teams of engineers have been boring deep underground in search of hot water. Almost 200 years after the naturally hot springs were first discovered in the area, they hope to further exploit this “geological anomaly” to generate renewable electricity and heat for Switzerland’s energy transition.

“It’s progressing well,” says Jean-François Pilet, director of Alpine Geothermal Power Production,External link which manages the drilling site. “At the start it was very slow but now things are accelerating slightly.”

The project’s goal is to harness water that is at least 110 degrees Celsius, with an ideal flowrate of 40 litres a second, to generate electricity. Deep underground the boiling point of water is higher than at ground level due to greater pressures.

Stage one has so far involved drilling vertically down to 1,800 metres. The rig is now being prepared to bore at an angle down to 2,500 metres. If the flowrate and water temperature encountered do not meet requirements, drilling may continue to 3,000 metres below the surface.

Click on the video below to find out more about the Lavey-les-Bains geothermal project.

Using special tools lowered deep into the borehole, engineers are able to build up a picture of the rock formations and identify the most productive open cracks where hot water is circulating.

It’s a bit like building a 3D puzzle, says Pilet.

When the drilling is completed in 2024, and the site is equipped with an accompanying power plant, the project should provide electricity for around 1,000 homes as well as heating for other facilities.

There is much riding on the CHF40-million showcase project, part-funded by the Federal Office of Energy. If it is successful, it will be the first operational deep geothermal project in the Swiss Alps and could pave the way for others.

Showcase project

“This project could also unlock the Rhône Valley, whose geothermal potential is believed to be significant,” says Fabien Lüthi, spokesperson and policy specialist at the Federal Office of Energy.

The authorities see geothermal energy as a key component of Switzerland’s long-term energy mix, alongside renewables like solar, wind and biomass.

But geothermal energy is still relatively small-scale in Switzerland. When it comes to electricity, none is currently being produced from geothermal sources. Low-depth geothermal energy (down to 400 metres below ground) produced mainly by heat pumps installed in homes and buildings, accounted for 1.3% of the country’s heating needs in 2020. The association Geothermie Schweiz [Geothermal Switzerland] believesExternal link that at least a quarter of the country’s heating needs could be met by hot underground sources – mainly low and medium-depth installations – by 2050.

The federal energy office is also confident: according to its 2050 scenario, 7% of national electricity consumption could be covered by geothermal sources.External link

Geothermal energy has great potential in Switzerland, says Benoit Valley, a professor at the Centre for Hydrogeology and Geothermics at the University of Neuchâtel.

“But projects can be difficult to implement and there are exploratory risks attached,” he says. “We need to accept that they involve considerable investment and that they won’t work each time.”

Opportunities and risks

Partly thanks to state subsidies and the proactive strategies of certain cantons, geothermal energy is enjoying renewed interest, with projects planned or underway in Vaud, Geneva, Jura, Fribourg, Basel, Thurgau and central Switzerland.

[The map below gives the latest overview of geothermal projects in Switzerland: green (project in operation); blue (work ongoing); yellow (in planning stage); red (project abandoned).]

“After some initial hesitation, Switzerland has finally set out to explore its deep subsurface and develop its geothermal potential,” geothermal expert Nicole Lupi wrote in a recent articleExternal link for the online site La Vie Economique.

In Europe, Iceland, France and Germany lead the way when it comes to geothermal energy projects. Switzerland, which doesn’t have a history of exploring for oil or gas, must build up its own geothermal industry “virtually from scratch”, said Lupi.

There are many potential obstacles. Deep geothermal projects can be held up by environmental concerns. Drilling work is also risky. Minor earthquakes forced projects at St Gallen (2013) and Basel (2006) to be abandoned.

More

St Gallen geothermal power project abandoned

The Jura government’s decision in February to relaunch a deep geothermal project at Haute-Sorne has sparked local concerns. Jack Aubry, the president of a citizens’ association in the Jura region, calls the idea of injecting water 5,000 metres underground a “dangerous scientific experiment”.

Pilet says that the Lavey project is safe, insisting that it is totally different to the St Gallen and Basel projects and constantly monitored.

“Here we are not drilling into a geological fault like at St Gallen. And we are not doing hydraulic fracking like at Basel,” he explains. “With our project we have a single borehole to extract water; we are not reinjecting water deep underground.”

Deep geothermal energy has many advantages over other renewables, says Lupi. It can be used continuously and ramped up in case of high daily or seasonal demand, which can help solve the winter supply problem and also reduce Swiss dependence on gas. The price of geothermal energy is also stable, in contrast to the volatile prices of fossil fuels, and it is not affected by climate fluctuations.

“All that is needed now for this renewable energy to gain sustainable momentum in Switzerland is a success story,” wrote Lupi in La Vie Economique. “The solution is literally under our feet.”

More

What the Ukraine war means for Switzerland’s energy policy

Replacing Russian gas

Lately, the climate crisis and the war in Ukraine have sharpened minds and underlined the need to develop renewable energy sources like geothermal to accelerate the energy transition and security of supplies.

Gas makes up roughly 15% of Switzerland’s final energy consumption and is mostly used for heating and cooking. Around half of imported gas, the equivalent of 16 terawatt hours (TWh), comes from Russia.

To reduce its reliance on Russian gas the Swiss government has been stepping up efforts to procure gas from other sources, secure additional storage capacity and import more liquefied natural gas. Switzerland must also expand renewables “with all our might, more speed is required. We also have to cut back on wasting energy”, said Energy Minister Simonetta Sommaruga in March without singling out any particular technology.

The geothermal industry is meanwhile lobbying hard for its piece of the pie. In April, a group of 150 leading European companies, including utilities and service providers, wroteExternal link to the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, urging her to develop a strategy to tap into geothermal energy and replace Europe’s reliance on Russian gas imports.

Geothermie Schweiz reckons geothermal energy could ultimately replace all Swiss imports of Russian gas – it’s just a question of more political will, it argues.

The geothermal energy association estimates that Switzerland could generate 17 terawatt hours of heat from underground sources a year. This could make up one quarter of the country’s needs, 70 Twh. Half could be achieved by doubling the number of low-depth sources like heat pumps, and the remainder from medium-depth projects like the district heating network at RiehenExternal link, near Basel, which makes direct use of hot underground water.

The Federal Office of Energy is more cautious, however. While the association’s estimates appear reasonable, there is not a single technology solution that can replace the gas supply, Lüthi says.

“In the current situation, time is of the essence and short-term as well as long-term solutions must be sought,” he says.

More

Can heat pumps solve the climate crisis? Can they also cripple the Russian economy?

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.