Previous

Next

Moss capsules (scale 16:1)

Dried moss capsules release spores after a drought. This particular moss is among the oldest plants on Earth. The picture is part of the biggest scanning-electron image ever printed. The original is 1.5 by 2.5 metres. (© Martin Oeggerli)

Surface of a water fern (scale 130:1)

The floating leaves of water ferns are around half a centimetre across. Their surface is covered with tiny structures that repulse water. Even when it rains heavily, these structures prevent the leaf from sinking.(© Martin Oeggerli)

Rust fungus spores (scale 8,960:1)

New spores on the surface of rust fungus. This fungus attacked a plant and killed it from the inside in just a few days. the diameter of each spore is only three to four thousandths of a millimetre. This picture was recently awarded the 2008 EMBO Journal Cover Contest prize for "Best Science Image". (© Martin Oeggerli)

Butterfly wing (scale 840:1)

A butterfly's wings are covered with a sort of coloured "dust" that vanishes if touched. A microscope view shows that the dust is made up of overlapping scales made up of chitin, a product that often constitutes the outer skeleton of insects. (© Martin Oeggerli)

Tulip pollen (scale 5,000:1)

Tulips produce millions of pollen grains. Their large colourful flowers attract insects looking for nectar, who then help distribute the pollen elsewhere. This photo finished third in the "Best Research Picture 2006" competition of German magazine Focus. (© Martin Oeggerli)

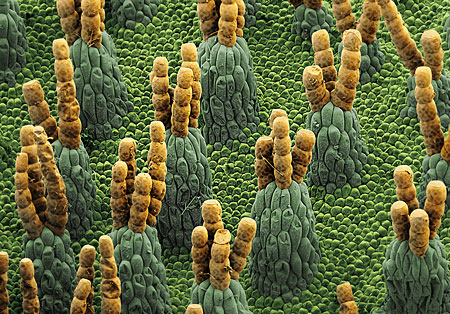

Tillandsia absorbent hairs (scale 300:1)

Tillandsia, a plant from central America that normally grows on others, has tiny absorbent hairs known as trichoma that allow it to absorb nutriments such as water and minerals from the air. (© Martin Oeggerli)

Gut bacteria (Escherichia coli) (scale 57,800:1)

The length of just one of these bacteria is approximately one thousandth of a millimetre. This type of bacteria is frequently used as a model organism in microbiology studies. (© Martin Oeggerli)

Mammalian cells (scale 1,600:1)

A mammalian cell divides. The cell's nucleus is split before the rest of the cell. This leads to the creation of two daughter cells, genetically identical to each other and to their parent cell. (© Martin Oeggerli)

The eye of the midge (scale 6,900:1)

A view of the outer edge of a non-biting midge's compound eye. Fully-grown animals are just two to three millimetres long. (© Martin Oeggerli)

A fruit fly's outlook (scale 1,600:1)

Insects have complex eyes that are in fact made up of a large number of individual eyes. The tiny fruit fly (one to two millimetres long) has bristles that grow between the individual building blocks and are probably mobile. (© Martin Oeggerli)

Martin Oeggerli takes a plunge into the world of the infinitely small.

This content was published on

May 28, 2008 - 16:46

Molecular biologist, photographer and artist Martin Oeggerli opens up new perspectives on the lives of the tiniest lifeforms. Using a scanning electron microscope, he takes for example images of pollen and bacteria before painstakingly colouring them electronically.

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.