Swiss glaciers remain under threat despite huge winter snowfall

After two years of extreme melting, Switzerland’s 1,400 ice giants are covered by thick layers of snow following up to six metres of snowfall this winter. Swiss glaciologist Matthias Huss talks to SWI swissinfo.ch about the impact of the recent dump and why the long-term future of the steadily shrinking Alpine glaciers remains grim.

Check out our selection of newsletters. Subscribe here.

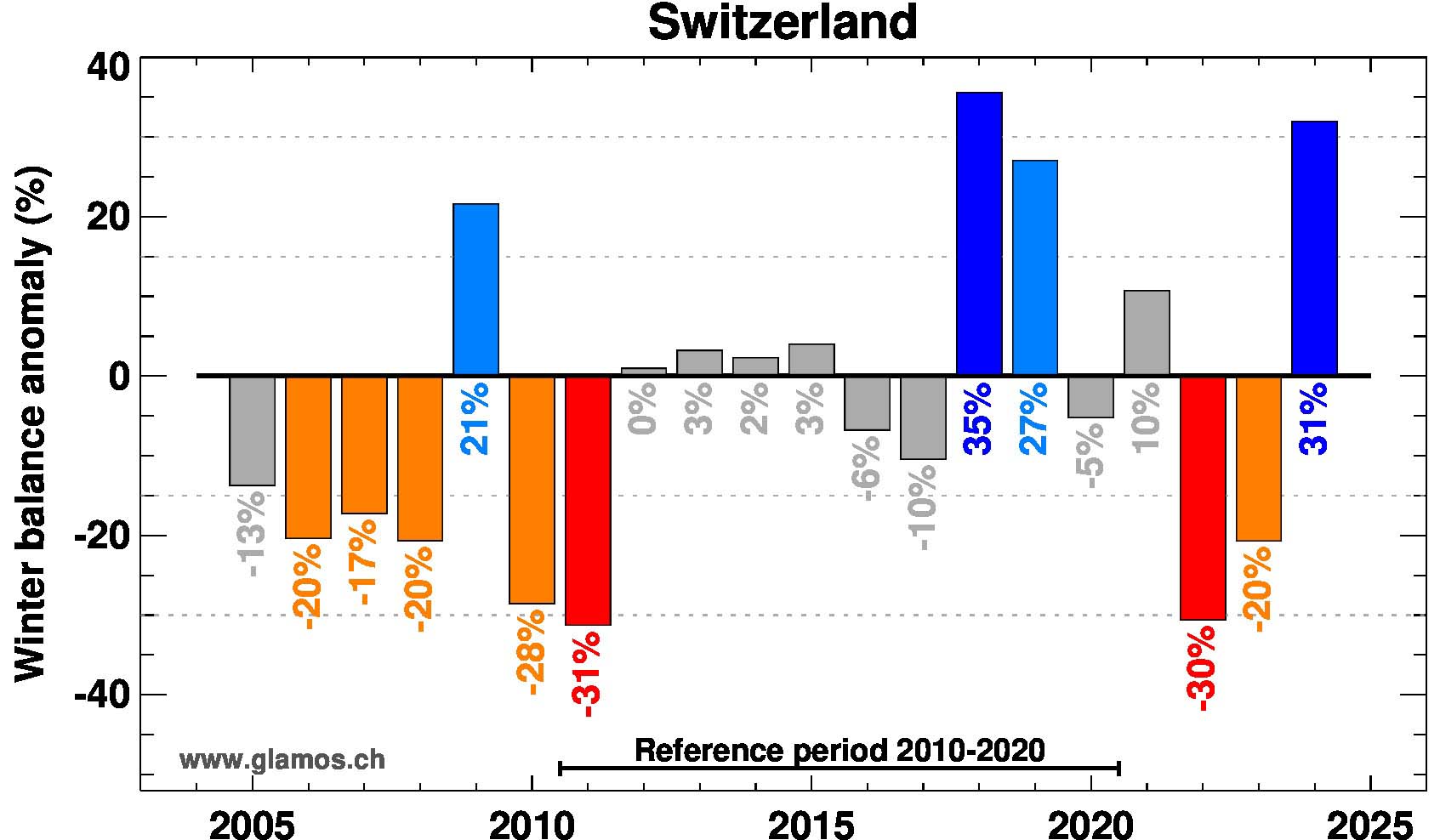

This winter was one of the best ever for Swiss glaciers in recent memory. Researchers at the Swiss Glacier Monitoring Network (Glamos) estimate that 31% more snow has fallen on average on the 1,400 glaciers dotted across the Swiss Alps than during the 2010-2020 reference period. In some places, a six-metre protective cover of snow has built up on the ice giants, situated above 3,000 metres.

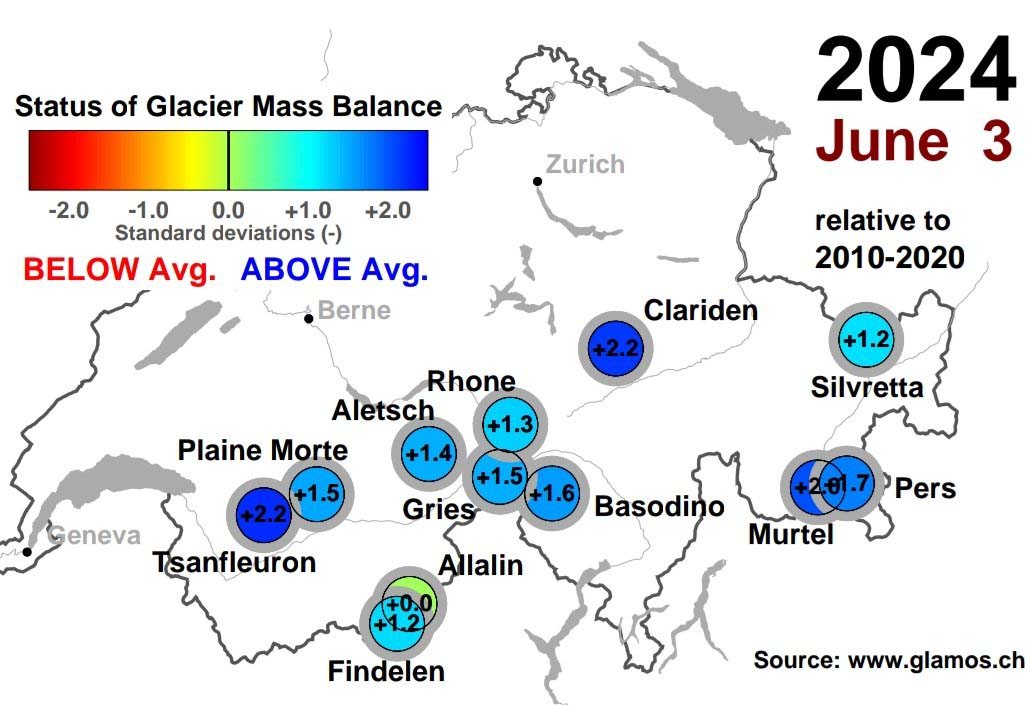

“This year’s weather is a blessing for Swiss glaciers so far,” says glaciologist Matthias Huss. The head of Glamos, who also teaches at the federal technology institute ETH Zurich, has spent 20 years in the field monitoring glaciers in Switzerland. In April and May 2024, he and his team visited 14 glaciers for end-of-winter measurements and extrapolated the data for their end-of-winter reportExternal link.

The situation up on the glaciers is very good, he says. All Swiss glaciers have seen an above-average surplus of snow, with roughly a third reporting record snow depths.

This winter’s dump represents the second-biggest accumulation of winter snow on Swiss glaciers over the past two decades. The biggest was 35% more snow in 2018.

Glaciers in Ticino, the Engadine region, in western Switzerland and on the northern side of the Alps benefited especially from heavy snowfall.

Very different to 2022-23

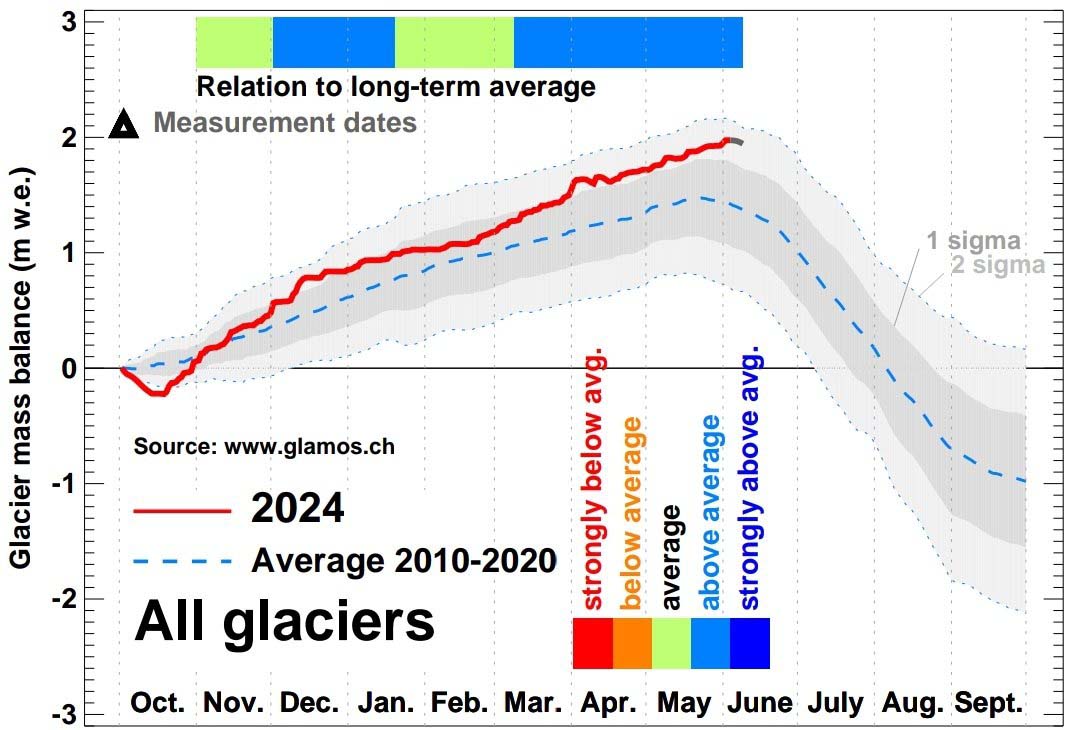

On Tuesday Huss announced on social media platform X that the peak of the snow accumulation had probably been reached the day before and that glacier melt in the Swiss Alps had begun.

“This is pretty late, but not exceptionally late,” he explains.

The situation is certainly very different to that of 2022 and 2023, when melting began in early May amid warm weather and thin snow cover. Ferocious summer heatwaves then caused Switzerland’s glaciers to lose 4% of their volume in 2023 – the second-biggest loss ever – after a record melt of 6% in 2022.

What does he forecast for 2024?

Despite the “double benefit” of a relatively late start to the melting and surplus snow cover, Huss says it’s difficult to predict what will happen, whether there will be a brief respite and recovery or slower melting.

“Everything is possible – but it obviously depends on the summer weather,” he says. “It’s not impossible that 2024 could be a balanced situation for Swiss glaciers with no losses.”

+ ‘It’s sad waving goodbye to a dying glacier’

The prediction is based on his modelling of estimated glacier shrinkage using the summer weather patterns observed in 2021, when it was fairly rainy and cool, and in 2022, when it was very hot.

+ Swiss glaciers melt faster than expected

“When looking at these two extremes, we see that at least for some glaciers it would be possible to have a moderate mass gain,” he notes. But even under the most positive scenario, some of the glaciers would still lose some ice mass.

But if the heatwave scenario is repeated, all glaciers would experience “strong losses”, but not as extreme as in 2022 or 2023, he adds.

Any hope for Swiss glaciers?

Since 1850, the volume of Alpine glaciers has decreased by about 60%. But in recent decades, Switzerland’s glaciers have been shrinking at unprecedented rates due to the climate crisis and shattering records. According to an international study published in 2023, Europe’s glaciers could practically disappear by 2100 under current climate conditions. A Franco-Swiss study from earlier this year predicts that the volume of ice in Europe’s glaciers will shrink by 34-50% by 2050.

From what we’ve seen this winter, is there any hope for Switzerland’s glaciers? “It depends on how you define ‘hope’,” Huss says. “There’s some hope for this year that the losses will not progress even more or that glaciers might record moderate losses or we even have a year with zero losses.”

But there is no way to compensate for the huge melting of the past 20 years, he says.

The formation of a glacier depends mainly on winter precipitation. This has to be great enough for some of the snow to last throughout the following summer. This sequence must be repeated for several successive years, until finally, under the pressure of its own weight the snow turns to ice.

If this ice layer is thick enough, it can flow under the influence of gravity. This transformation of snow to ice is often a long and complex process, both its nature and the time involved depend on ambient temperature and the depth of further, overlying snow. Changes take place fastest in temperate regions, like the Alps and slowest in the polar regions, like the Canadian Arctic.

In the transformation of snow to ice snowflakes change to grains which become rounded and granular, like coarse sugar. As the snow becomes compressed it becomes harder and denser. Over one to two years the snow turns into firn; this is an intermediate stage in its transformation to ice. The entire process to become glacier ice can take five years.

Source: AlpecoleExternal link, University of Zurich

“In that sense, there is no hope that the glaciers will return to a healthy state,” says the glaciologist. To do so would require heavy winter snowfalls and very cool, rainy summer weather for several decades.

“But this is very improbable given the current climate narrative,” he notes.

Edited by Virginie Mangin/ts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.