The international consequences of a glacier-free Switzerland

Switzerland’s glaciers could almost disappear due to global warming. Melting ice in the Alps will have an impact on large rivers in Western Europe – but it won’t stop there.

On the Jungfraujoch pass, nearly 3,500 metres above sea level in the Bernese Alps, Andreas Linsbauer takes a long metal rod and jams it into the fresh snowpack. After four metres, he can’t push any further. He’s hit the hard layer of snow that covers the glacier.

“At first glance I would say the conditions are not so good,” Linsbauer, a glaciologist at the University of Zurich, says. There is usually six to seven metres of fresh snow here at the end of winter.

Linsbauer is on the Aletsch, the longest glacier in Europe, to demonstrate how to measure the amount of snow that accumulates on the glacier in a year, a critical sign of how the glacier may fare in the warmer months to come. “The measurement method has been pretty much the same for more than a century,” he says.

With our SWIplus app, you receive a summary of the most important news from Switzerland every day, plus the main news programmes from Swiss public television and personalised monitoring of developments in the canton of your choice. Find out more about the app here.

Recently, this and other measurements have been cause for concern: 2022 and 2023 were the worst years for glaciers on record.

“The last few years have been extreme,” says Matthias Huss, director of the Swiss Glacier Monitoring Network (GLAMOSExternal link), during a conference organised at the scientific research station on Jungfraujoch on World Glacier Day (March 21). Since the 1970s, the average temperature in the Swiss Alps has increased by 3°C, twice the world average.

It is still too early to know how the Aletsch and the other Alpine glaciers evolved during the winter (official measurements by GLAMOS begun at end of March). However, early observations suggest that the amount of snow on the glaciers is quite a bit below the average, particularly in the eastern regions of the country.

The continued melting of glaciers caused by global warming will have many wide-ranging consequences, Huss warns. The Alpine landscape will change significantly, and new lakes will form. Landslides and floods will become more frequent. In hot, dry periods, water shortages will become more pronounced. He says the retreat of Swiss glaciers will be felt beyond the country’s borders, all the way to the ocean.

The end of glaciers in Switzerland in 2100?

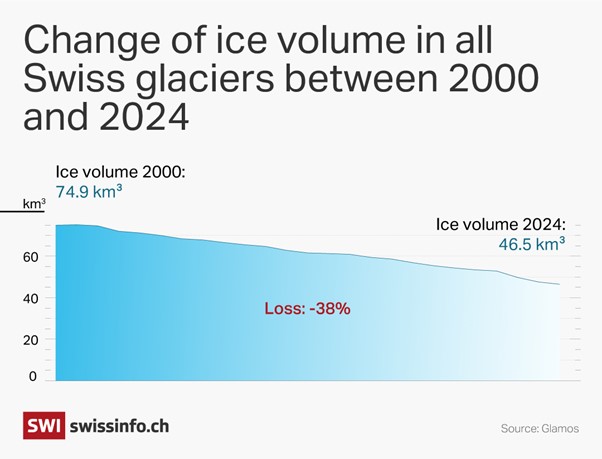

Swiss glaciers have lost an area of ice the size of canton Uri – 1,000km2 – since 1850. More than 1,000 small glaciers have disappearedExternal link. The volume of Switzerland’s current 1,340 glaciers has shrunk by nearly 40% since 2000. The average loss corresponds to more than one metre of ice thickness per year.

Looking at the immense river of ice and snow coming down from the Jungfraujoch, it is hard to imagine that the Aletsch could be gone in the next 75 years. On Konkordiaplatz, the area where the four glaciers that eventually go on to form the Aletsch meet, the ice mass is 1.5km wide and 800 metres thick.

Yet according to new model predictions, which for the first time also consider the scorching summers of 2022 and 2023, even Switzerland’s largest and highest elevation glaciers will disappear by 2100 if greenhouse gas emissions don’t drop significantly.

“If, however, we were to meet the target set by the Paris Climate Agreement and stabilise global warming between 1.5°C and 2°C, our grandchildren could still see at least a quarter of Switzerland’s glaciers,” saysExternal link Daniel Farinotti, a glaciologist at ETH Zurich.

Less water in major European rivers in summer

Glaciers store water from snowfall in winter and release it in summer. The meltwater is used to produce energy, irrigate fields and as drinking water for the Swiss population.

Alpine ice water feeds major Western European rivers such as the Rhine, Danube and Po. Meltwater from the Aletsch goes into the Rhone, the river that flows through canton Valais, Geneva and southern France before reaching the Mediterranean Sea. Almost 30% of the Rhone’s flow in Geneva comes from glaciers, and this can be even higher in times of droughtExternal link.

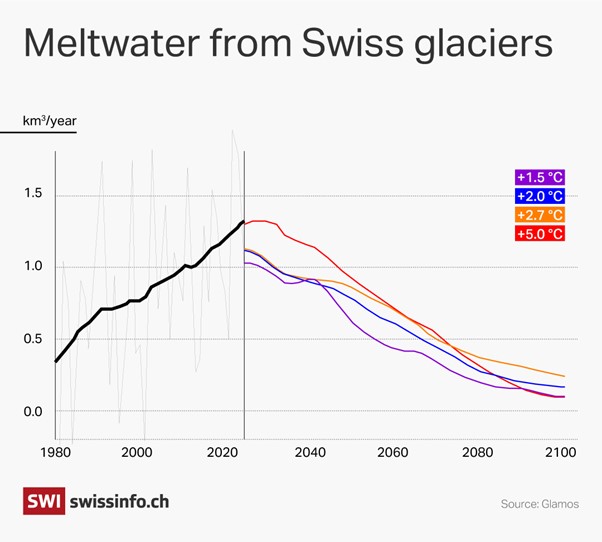

From 1980 to the present there has been an increase in the amount of water melting from glaciers. This is good for Europe’s large rivers, Huss says. However, glaciers have melted to such an extent that they will soon release less water. “Peak water”, that is, the time when meltwater runoff reaches its maximum level, has either already been reached in the Alps or it will be in the next few years, he adds.

“We have already squeezed the glaciers like lemons.”

Matthias Huss, glaciologist

This means there will be less water in Alpine valleys and major European rivers. It is possible that this will affect navigation, agriculture, ecosystems, drinking water resources and energy production. In France, Rhone water is used by some 20 hydroelectric plants and cools the reactors of four nuclear power plants.

In the future, even with warmer summers and a high melt rate, the flow of meltwater will drop. Glaciers will no longer be able to mitigate the effects of increasingly frequent and prolonged droughts. “So far the water shortage has been masked by the additional water coming from the melting [of glaciers], but now the phenomenon is slowly diminishing,” Huss says. “We have already squeezed the glaciers like lemons.”

Peak water has already been reachedExternal link in most other basins dominated by many small glaciers, for example in western Canada and South America. In Central Asia and the Himalayas, annual glacier runoff is expected to peak around mid-century.

>> The graph below shows that the peak water of Swiss glaciers has been reached, regardless of the climate warming scenario considered:

Sea levels could rise one metre by 2010

The global melting of mountain glaciers and ice caps in Greenland and Antarctica is a significant contributor to sea level rise, explains Daniel Farinotti. Melting glaciers caused up to 21% of the sea level rise recorded between 2015 and 2019, according to a studyExternal link published in Nature in 2021.

The melting of Swiss glaciers and the Alps in general contributes only in a small way to rising sea levelsExternal link. However, glaciers are melting all over the world and will release huge amounts of water in the coming decades. Depending on the climate scenario, sea levels could rise between 50cm and one metre by 2100.

Tourism in a glacier-free Switzerland

Alpine glaciers are not only a valuable water reservoir. They also attract visitors from all over the world every year. In 2024, more than one million peopleExternal link climbed the Jungfraujoch, where Europe’s highest train station is located.

If there are no more glaciers, destinations such as Zermatt, at the foot of the Matterhorn, or the Jungfraujoch, which are known all over the world, would need to present themselves in a different light, writes the Swiss Academy of Natural Sciences in a recent fact sheetExternal link.

The Swiss tourism industry is closely monitoring the consequences of climate change, André Aschwanden, spokesman for Switzerland Tourism, writes in an email to SWI swissinfo.ch. Mountains and glaciers have always been and remain very important tourist attractions in Switzerland, but it is difficult to predict to what extent the melting of glaciers could affect tourist numbers, he says.

“We feel that a Switzerland without glaciers would be less appealing to UK visitors than a Switzerland with,” says Els van Veelen of Walkers’ Britain, a British tour operator offering hiking holidays in Switzerland and Europe. At present, the melting of the Alpine glaciers has no negative effects in terms of bookings. It has, however, led to an increase in rockfalls in some places. “In the future, we may be forced to alter some of our routes or itineraries,” she says.

Matthias Huss says he’s sure there will still be some glaciers in Switzerland when he retires, but he thinks his children or grandchildren could grow up in the Alps without glaciers. “It’s hard to accept that this could be the reality in the future.”

Edited by Gabe Bullard. Translated from Italian by DeepL/vdv/ts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.