What it takes to preserve groundwater across borders in Geneva

The Genevese aquifer between Switzerland and France has served as a global model for dividing precious groundwater between countries. But amid increasing droughts and population growth, even this exemplary water reserve is reaching its limits.

When the most important underground source of drinking water in canton Geneva reached an all-time low in the mid-1970s, there were two options: build a new plant to capture water from Lake Geneva or artificially replenish the aquifer.

The first would have cost about CHF150 million ($165 million) and was feasible. The second cost just CHF20 million but posed a significant technical challenge.

More

Newsletters

Authorities went for the second option, and it paid off; the water level stabilised, and the population of Geneva and neighbouring French municipalities had enough drinking water.

But nearly 50 years later, population growth and extreme droughts due to climate change are again putting the water supply under pressure. “The drought in the summer of 2003 was an early wake-up call,” says Gabriel de los Cobos, a hydrogeologist who was involved in the management of the aquifer for the Canton of Geneva from 1998 to 2023.

Then came droughts in 2022 and 2023. “If what happened in the last two summers occurs at other times of the year and in a prolonged way, we will have a problem in the future,” he warns.

Authorities in Switzerland and France, who signed a historic agreement about sharing groundwater resources that served as a model in other regions of the world, must now re-negotiate a sustainable solution.

‘Risky’ decision

Ten wells in Switzerland and four in France bring the groundwater to the surface, which mainly originates from the Arve, an Alpine river that rises in the Mont Blanc massif.

The Genevese aquifer provides about 20% of the drinking water consumed in canton Geneva. Together with Lake Geneva, it ensures the drinking water supply for about 700,000 people in the cross-border region.

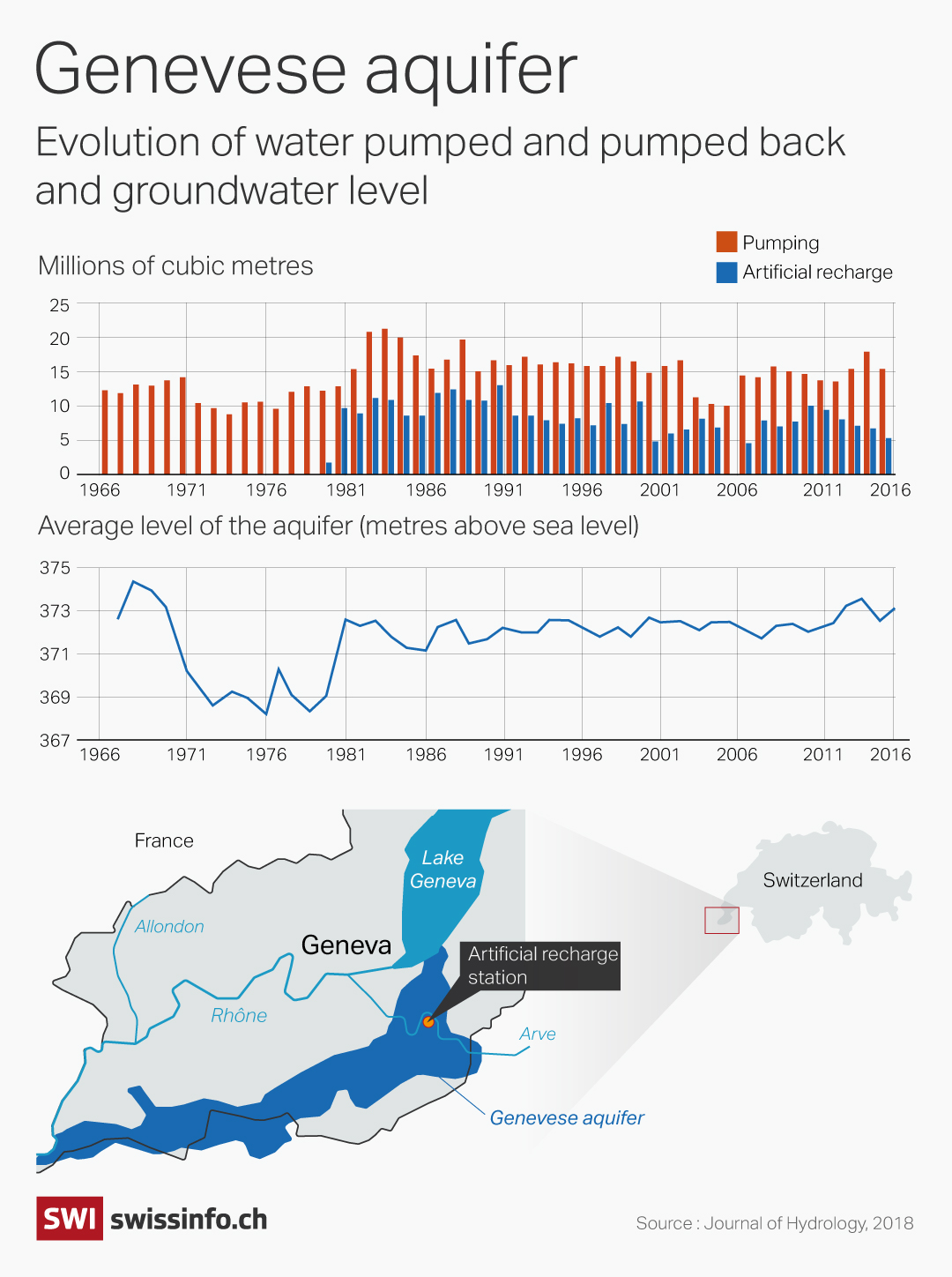

In the 1960s and 1970s, the level of the aquifer dropped dramatically as a result of excessive and uncoordinated exploitation on both sides of the borderExternal link. Some wells dried up and were closed.

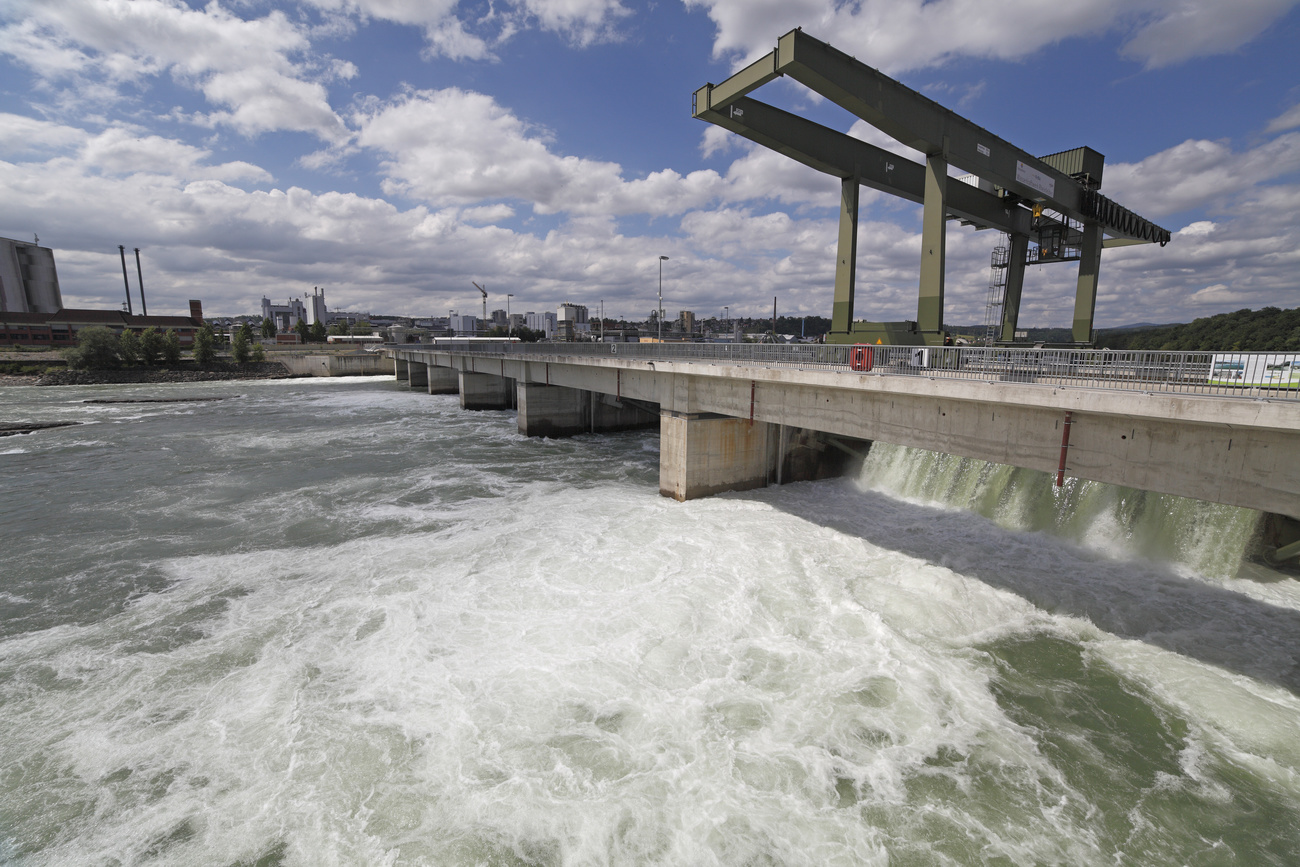

The decision to restore the aquifer with water from the River Arve was “risky”, says Gabriel de los Cobos. “You needed the right hydrogeological conditions and, above all, good-quality water to put into the aquifer,” he says. Authorities feared that an artificial recharge could pollute groundwater reserves.

So managers built a recharge station that filters the water from the Arve. The water then seeps into a five-kilometre underground drainage network. The aquifer is replenished in autumn and winter, when the river water is clearer with less sediment. Shortly after it was commissioned in 1980, the station managed to rebalance the groundwater level. On average, the plant in Vessy allows 8-10 million cubic metres of water to be artificially injected every year – a process that has since become common practice worldwideExternal link.

Neither Swiss nor French

The Genevese aquifer is also a success for other reasons.

The conventionExternal link signed by canton Geneva and the French Prefecture of Haute-Savoie in 1978 was the first to involve local authorities of two countries in the management of a cross-border aquifer.

Local municipalities have better knowledge of their water supply issues and can act more effectively than national authorities, explains Gabriel de los Cobos.

“The agreement worked because no one talked about Swiss or French water. It’s simply drinking water that everyone needs and that’s what matters,” he stresses.

Canton Geneva financed the construction of the recharge station. French municipalities close to the border were granted the right to pump up to two million cubic metres of water per year free of charge. They have to pay for up to a further five million.

Consuming water ‘like there’s no tomorrow’

But elsewhere, water shortages are looming. Since 1980, groundwater resources have declined almost everywhere in the world, and the decline has accelerated since 2000, according to a recent studyExternal link involving the federal technology institute ETH Zurich.

From the United States to the Mediterranean region to Australia, the world “is squandering groundwater like there’s no tomorrow”, Hansjörg Seybold, professor of physics and environmental systems and co-author of the study, said in a press releaseExternal link. This is especially true for agriculture and crop irrigation.

Excessive groundwater pumping has an impact on humans and ecosystems, notes co-author Debra Perrone, an associate professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “Wells can run dry, leaving people without access to water for drinking, cooking and cleaning,” she writes in an email.

It also has an impact on river flows and can cause land to sink, affecting homes and infrastructure. In coastal regions, when groundwater levels fall, seawater can infiltrate and salinate wells, which makes groundwater unusable for human consumption and irrigation.

Climate change is also exacerbating groundwater scarcity. The climate is becoming hotter and drier, and agriculture requires even more water. Due to reduced rainfall in some regions, groundwater supply recovers more slowly, if at all, according to the study.

But Seybold says the trend can be reversed. The Genevese aquifer shows that groundwater levels do not always have to go down, he points out.

Inspiring cross-border agreements

The Franco-Swiss agreement on the Genevese aquifer has inspired other regions of the world, according to Laurence Boisson de Chazournes, a professor of international law at the University of Geneva.

This is the case in Sudan, Chad, Libya and Egypt, which share the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer, located deep in the Eastern Sahara. It is one of the largest underground water reserves in the world.

Jordan and Saudi Arabia also have a cross-border water deal. In Latin America, an agreement on the Guarani AquiferExternal link, bringing together Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay, came into force in 2020.

The key to peaceful management of a climate-disrupted water cycle is to “give up ‘water nationalism’ and focus on dialogue”, says Jean Willemin of the Geneva Water Hub, a research and policy institute.

More

How are you? What is on your mind? Take part in our big survey

Time for a new agreement

But the Genevese aquifer is under increasing pressure, and the current agreement has reached its limits. The surrounding population is growing rapidly and could reach 1.3 million by 2040, compared to about one million in 2020.

If there is an autumn or winter drought, as has been the case in recent years, it will become more difficult to replenish the aquifer with water from the Arve, Gabriel de los Cobos points out.

Public authorities in Switzerland and France are currently negotiating a new agreement. According to the proposal currently on the table, France would have to pay for every cubic metre of water it uses. Gabriel de los Cobos, who continues to follow the work of the responsible committee, says this aims to encourage more economical water use.

The price would come with more decision-making power, and the French municipalities would receive the right to pump more water from the Genevese aquifer. In turn, they would have to limit pumping into other smaller aquifers in the region, particularly in those that feed rivers flowing into canton Geneva which ran dry last summer. They would also be required to carry out more studies on the Genevese aquifer on their territory.

The new agreement is expected to come into force in November. “If no sustainable solution is found, only one alternative remains: reduce water consumption,” says Gabriel de los Cobos.

This article was corrected on 3 June to specify that Gabriel de los Cobos was involved in the management of the Genevese aquifer as hydrogeologist for the Canton of Geneva from 1998 to 2023.

Edited by Sabrina Weiss/ts

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.