Concrete: the building material of the 20th century

Architecture fans wax nostalgic about concrete, while others see it as the epitome of coldness and ugliness. A brief history of Switzerland’s love-hate relationship with concrete.

Switzerland is a land of concrete. During the postwar years, it used more concrete per inhabitant than other European countries, which were rebuilding their bombed-out cities. Even today, over half a tonne of concrete is used annually for every Swiss resident, and the small Alpine nation regularly figures among the world’s top five consumers of concrete.

The Swiss appetite for concrete was, and is, mostly due to large-scale infrastructure projects – like the Grande Dixence dam in canton Valais. Between 1953-1961, up to 1,500 workers at a time worked on the structure, which is higher than the Eiffel Tower.

Among them was a young man named Jean-Luc Godard, who worked there as a telephone operator – and who devoted his first short film to the building project. The French-Swiss film director’s early work describes the site as a giant “organism of iron and steel”, which tears rock out of the mountain, and pumps it into its “metallic heart” to grind it up and mix it with cement.

Young Godard was able to sell his film to the dam operators – it is really an advertisement for concrete. The film’s underlying message is that concrete is nothing but transformed rock. To this day, the concrete industry in Switzerland advertises the material as a local product, as natural as cheese and milk.

An exhibition at the Swiss Architecture Museum presents original drawings, models and photographs from the three major architecture archives in Switzerland to illustrate the role of concrete as a cultural and architectural phenomenon. The exhibition runs until April 24, 2022.

Otherwise poor in natural resources, Switzerland has an endless supply of rubble, gravel and most of all limestone, which is a key material for making cement. Numerous cement factories sprang up in the second half of the 19th century in the areas around quarries in Switzerland.

While in the United States the antitrust battle was led against the oil and steel cartels, Social Democrats in Switzerland struggled to break the “cement trust” – the concrete industry was that powerful. In the 1990s large parts of it were absorbed into the multinational Holcim-Lafarge, which today dominates the global concrete market.

Yet concrete is not just a building material. It is also a symbol of the modern world. “Concrete jungle” has become a powerful political term used to rally the troops on both left and right. For some people, buildings mostly made of concrete convey a sense of style. For others the material is still the epitome of coldness and ugliness.

Let us take a closer look at the history of this well-known building material, which triggered both dreams and nightmares in the 20th century.

Concrete rises to the surface

Back in the middle of the 19th century, it was discovered that concrete reinforced with steel could be formed into stable shapes. During the subsequent period of industrial expansion, concrete followed steel in becoming a traditional modern building material. Concrete as the material of the future had at last “completely overcome the inertia and unreliability of natural materials like marble, sandstone and wood”, trumpeted the “Cement Bulletin”, a PR publication of the Swiss concrete industry in the 1920s.

- Salvatore Aprea/Nicola Navone/Laurent Stalder (eds.): Concrete in Switzerland. Histories from the recent past. 2021

- Nadine Zberg/Tobias Scheidegger. Grau. Beton als Chiffre.External link In: Gegen|Wissen, 2020 (cache 01).

- Sarah Nichols: Pollux’s spears. In: Grey Room 1.2018.

- Georges Spicher/Hugo Marfurt/Nicolas Stoll: Ohne Zement geht nichts: Geschichte der schweizerischen Zementindustrie. 2013.

- Adrian Forty: Concrete in the Cold War. In: David Eugster/Sibylle Marti: Das Imaginäre des Kalten Krieges. 2015.

- Interview with Sarah Nichols, curator, Exhibition on concreteExternal link

- Interview with Nadine Zberg, University of ZürichExternal link

- Interview with Evan Panagopoulos, ExplorabiliaExternal link

Initially there were fears that the combination of cement, stone and a steel framework might not be stable enough. So concrete manufacturers created spectacular demonstrations to try to convince the public. At the National Exhibition of 1883, the Vigier company demonstrated how much weight a concrete bridge could take – it collapsed after 38 tonnes of timber had been dumped on it. Scientific proof of load capacity was later provided by the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology (EMPA), founded in 1880 as part of the federal technology institute ETH Zurich. It proved again and again just how much punishment concrete structures could take. Concrete became not just a byword for design flexibility, but for sturdiness and stability.

But during this period concrete was not considered very aesthetic, and it remained hidden away for many years, generally reserved for foundations, supporting columns or sewage systems. When it appeared in the light of day, it was used to cover over foundations, but made to look like natural stone.

Around 1900, early conservationists who were preoccupied with preserving as much of the Swiss natural landscape as possible, shared their concerns about the “dead layer of concrete” on retaining walls in the Alps. They recommended roughening concrete so that the natural stone in it is visible. Concrete should look to the passing eye like natural conglomerate, or highly compressed puddingstone rock.

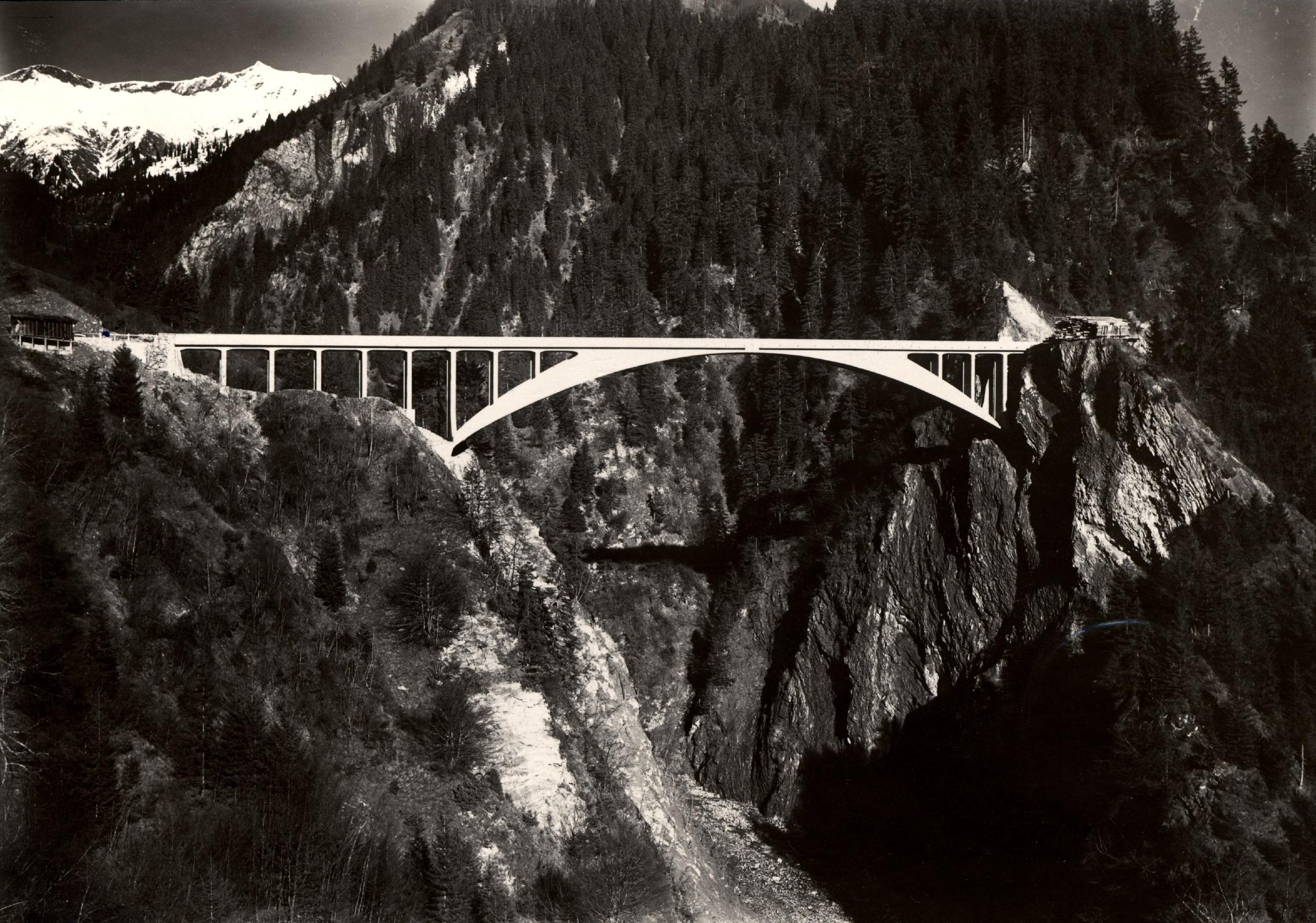

Maillart’s concrete bridges make their mark

In the postwar years more and more people got excited about concrete’s aesthetic qualities. In 1947, the Museum of Modern Art in New York held a retrospective of the work of Swiss engineer Robert Maillart. In its press release the museum described how Maillart’s concrete bridges sprang over rivers and gorges with the elegance of greyhounds. Only stupidity could account for the fact that the work of this genius had been relegated to remote valleys, the curators said. They mocked Zurich’s Stauffacher Bridge, where Maillart’s original concrete core was covered with granite and sandstone. Narrow-minded city officials had hidden away what Maillart had raised to the level of famous sculptors like Brancusi.

Le Corbusier-style raw concrete

The central figure using concrete in the postwar years was the Swiss architect Le Corbusier, who deployed it, not polished or whitened, in its raw state. The style, known as “Brutalism”, includes various experiments with concrete.

The architecture style known as “Brutalism“, based on Le Corbusier’s “raw concrete”, has little to do with the idea of brutality, but is more about architectural production. The buildings should have an iconic recognition factor, materials should be unrefined – “as found” – and the construction aspect should be plain to the eye – nothing whitewashed, painted over or decorated.

Concrete was only one of the building materials used, although the label “Brutalism” is today often used as a label for any building where a great deal of concrete surface is visible.

One of the most impressive “Brutalist” buildings was designed by the Zurich sculptor and architect Walter Maria Förderer. It is the St. Nicolas church in Hérémence in canton Valais, built between 1967-1971. The design, which plays with bold projecting elements and windows, as in many of the Brutalist churches designed around that time, evokes radical change and openness. Located just a few kilometres from the Grande Dixence dam, Förderer based his design on the idea of a cliff that has toppled down into the valley. Here, concrete becomes a second crust of the Earth, a new nature. The architecture is seen as part of the landscape, in which the boundary between nature and artistry disappears.

The influential Atelier 5 architect group in Bern used concrete in a gentler fashion. They frequently utilised concrete in their buildings, as they had committed to the construction concept of concrete with its superficial roughness and imperfections. Atelier 5 architect Jacques Blumer described concrete as a material that “facilitates both simplicity in expression and simplicity in detail”.

This belief in simplicity became their agenda. Atelier 5 was organised cooperatively – no masters or star architects – and their aim was to build accommodation for workers. Although the buildings ended up being lived in mostly by the educated middle-classes, the architects succeeded in creating high-density housing projects that were extremely liveable, more like medieval towns than the wide open spaces of modernity.

Yet their landscaped planning would not have been possible without concrete. The Halen Estate, a housing complex in Bern, includes spacious underground parking; the city could only be reached by car.

The major energy infrastructure projects of the 1950s were followed in the 1960s by the extension of the motorway network, which also used huge quantities of concrete. It is here that Swiss concrete architecture proudly demonstrated the progress it made possible, for example in Rino Tami’s design for the entrance portals to the Gotthard Tunnel in the 1960s.

From bunkers to prefab housing

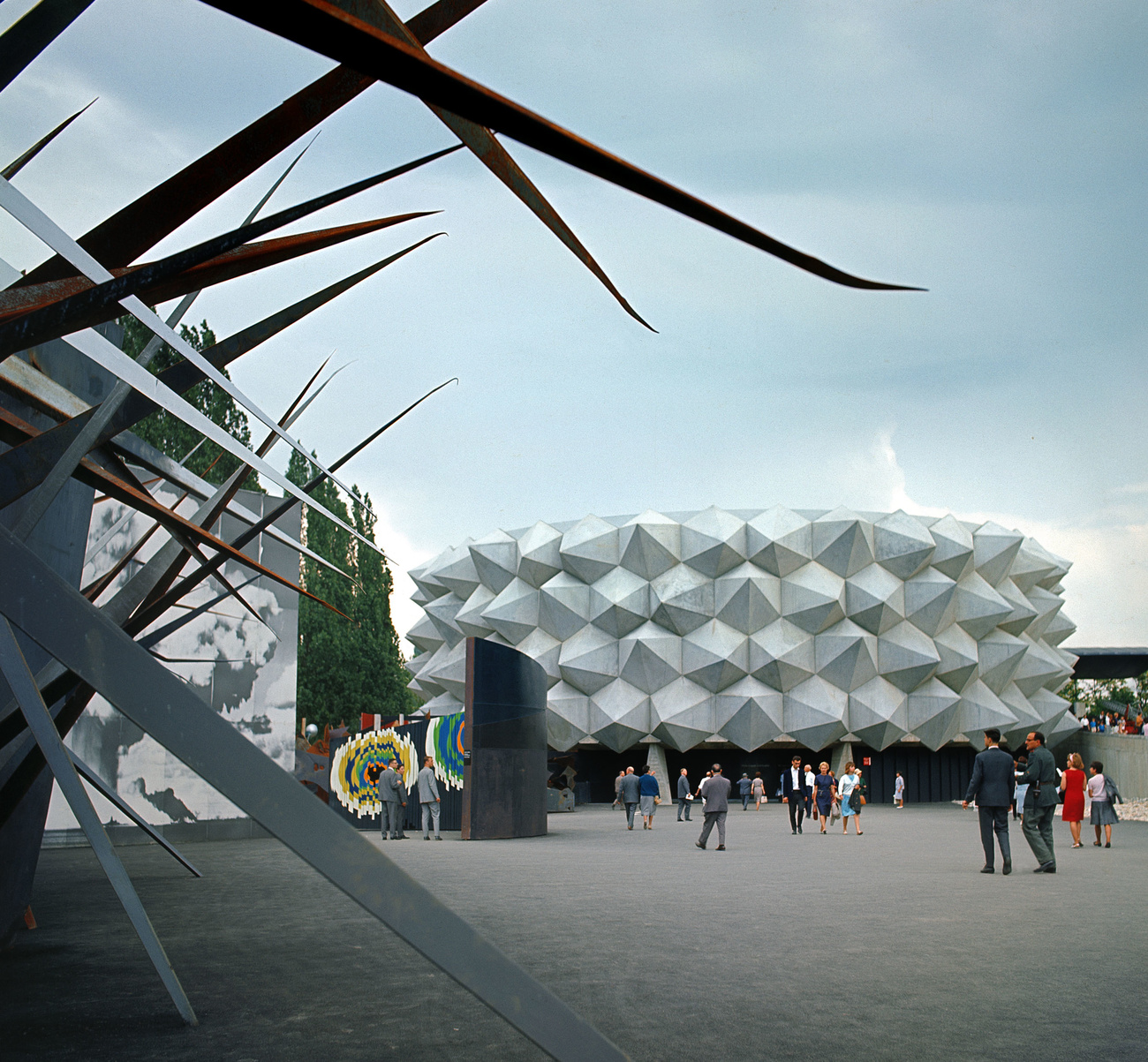

Concrete had no clear political allegiance during the march of modernity. Even the Swiss army pavilion at the National Exhibition in 1964 recalled the monumentalism of Brutalist buildings. In this structure, Switzerland appears as a defensive hedgehog bristling with 141 concrete quills, each one weighing 3.5 tonnes.

According to historian Adrien Forty, concrete symbolised both the promise of a better world and the fear of mass destruction. Bare concrete could be associated with progressive architecture, but also with the walls of the underground bunkers that were built in Switzerland during the Cold War to protect citizens against Russian nuclear bombs.

Amid the ongoing arms race and competition between political systems, concrete was widely used in eastern and western European countries in an attempt to quickly resolve the housing shortage in the postwar era. The grey eastern “prefab” look so stigmatised in the West was not that different from what the capitalists were putting up. Their housing projects were based on the same idea: readymade elements were mass-produced and then assembled to make apartment buildings that were affordable or at least profitable for investors. This was the third great stimulus to the use of concrete in Switzerland: in the central Plateau region apartment blocks started sprouting up everywhere. The pace of construction was fast. Sometimes it was about keeping costs down, sometimes it was more about profit than aesthetics.

In the early 1970s, the economic boom collapsed and so did enthusiasm for progress. The Club of Rome group declared that there were limits to growth, and the 1973 oil crisis showed this for all to see – economic and cultural decline now went hand in hand.

The fast-paced building of recent times was now branded as “environmental degradation” (from the title of a book by the architect Rolf Keller), and living in large housing projects became regarded as soul-destroying and inhuman. Beautiful architecture, said one prominent member of the Federation of Swiss Architects, had become so rare that you had to search for it like “raisins in rising dough, in a crust of concrete spreading over the earth”.

Concrete became a byword for dystopian progress. It was not by chance, therefore, that the concrete industry began in 1977 to award a prize for the most beautiful buildings in Switzerland – to make up for all the bad press they were getting.

Concrete jungles

In the 1970s “concrete jungles” blighting the landscape started to appear in political manifestos. The earliest of these was from the National Action party, which sought to justify their initiative against “too many foreigners in Switzerland” not only with racist stereotypes but also with environmental concerns. Immigration meant more people, more people meant more urban sprawl, and urban sprawl meant concrete. As recently as 2020, the Swiss People’s Party opposed the concreting over of Switzerland – somewhat unfortunately with an image of the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin.

In the late 1970s Social Democrats got in on the act. Concrete is synonymous with profit-driven growth and real estate speculation, they declared. When youth movements rebelled in Swiss cities in the early 1980s, they called for the eradication of concrete. “What a pity that concrete doesn’t burn,” said the flyers.

Even today, concrete gives rise to sharp divisions in society. Whenever tabloids ask their readers to vote for the ugliest building in Switzerland, the dubious distinction tends to go to buildings with a lot of concrete. At the same time, architecture awards are often given to buildings that show a healthy respect for concrete. Houses made with carefully poured raw concrete are found in wealthy residential areas. Concrete may have lost its aura of stark simplicity, but architects still appreciate it as an “authentic” material.

For many years, the debate about concrete has extended beyond aesthetic concerns to the environmental damage it causes. Behind China and the United States, the cement industry is regularly cited as one of biggest producers of greenhouse gases. And the production process for concrete is extremely energy intensive, generating massive CO2 emissions.

In that respect too, concrete is a typical material of the century gone by.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!