Covid-19: Switzerland can smile again. But for how long?

While many countries, including Switzerland, are returning to normal, China is struggling to contain a new coronavirus wave and many of the world’s population have still not received their first Covid jab.

As of today, April 1, Switzerland is back to “normal”. On Wednesday, the Swiss government decided to lift the last remaining restrictions: no more compulsory masks on public transport and in health facilities, and no more isolation for people who test Covid positive. People are “smiling again”, newspapers report, and optimism is soaring, according to a surveyExternal link conducted by the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation (SRG), SWI swissinfo.ch’s parent company. However, half of the people surveyed expect the worst this winter, and mask and Covid certificate requirements continue to divide opinion.

I myself am somewhat hesitant about the decision to do away with mask requirements altogether: since I stopped wearing a mask in shops and supermarkets, my immune system has rebelled and become less responsive. As a result, I got bad flu.

Epidemiologist Marcel Salathé was certainly not happy with the government’s decision. In an interview, he said he was “worried” about the rapid increase in cases and urged the Swiss government to wait before lifting all restrictions – an invitation that went unheeded. Even the words of the Director General of the World Health Organization (WHO), Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, who calledExternal link the current increase in cases “the tip of the iceberg”, do not seem to have prompted caution.

More

Coronavirus: the situation in Switzerland

What do you think about the abolishing of Covid-19 measures? Are you relieved or worried? Let me know what you think!

Too early to celebrate

My colleague Simon Bradley recently spoke to Antoine Flahault, director of the Institute of Global Health at the University of Geneva about the recent global increase in cases. Flahault speculates on a few reasons for the resurgence – citing air pollution among them – and says that Covid-19 should continue to worry us: it is not a flu and not a cold, but it is a disease that can have severe consequences, including Long Covid, he says. Simon Bradley tells us more about his conversation with Flahault:

Flahault was very clear that the pandemic is far from over and he is concerned about the high mortality rates, especially in Europe. Governments loosening restrictions and Omicron’s new BA.2 subvariant – around 30% more contagious – could be responsible for the recent surge in cases. But Flahault also supports the theory that winter air pollution and fine particles could be linked to the recent peaks in Covid-19 infections in Europe.

And what about Switzerland? Simon Bradley also explored with Flahault the measures taken and the risks the country faces:

Switzerland has handled the pandemic well from the start, says Flahault. But Swiss vaccination coverage is fragile (69%), and the expert warns that if immunity begins to wane, the country could find itself in the same situation as South Korea, which recently experienced a wave of admissions to intensive care units and still records 300 deaths on average every day. It also leads in the average daily number of new reported cases. Flahault says we shouldn’t jump too quickly to declare the new Omicron BA.2 subvariant as mild.

More

What’s behind the latest surge in Covid-19 cases?

Immunity still a challenge

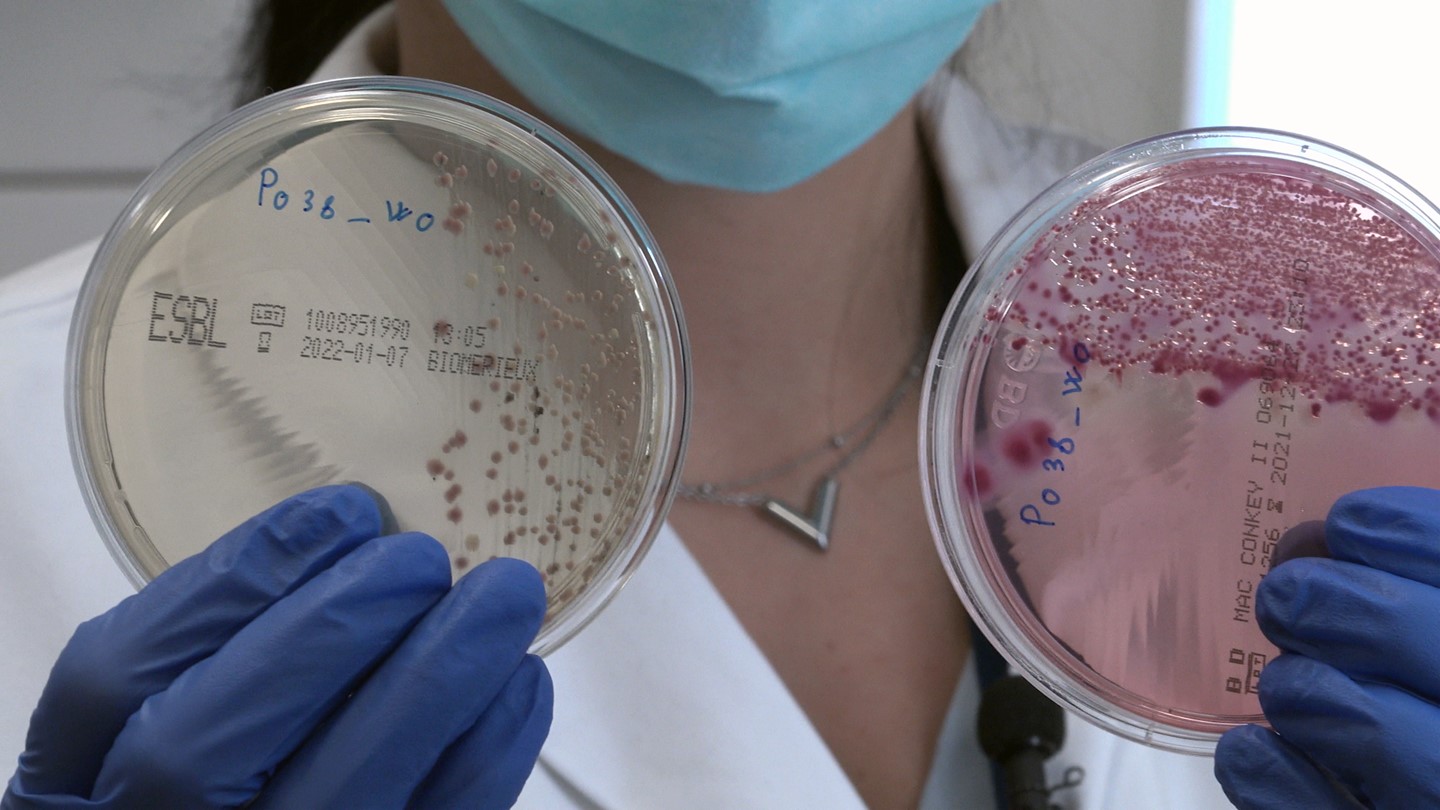

Another reason why experts and pundits are urging caution is that two years into the pandemic, measuring the population’s immunity is still a challenge, writes my colleague Jessica Davis Plüss. “Statistically, we still don’t know what levels of antibodies are needed to determine whether a person is resistant to the infection, whether they can transmit it to others, or how protected they are from the disease,” virologist Didier Trono said in an interview.

The wave caused by the Omicron variant has indeed shown that current diagnostic measurements do not provide reliable information on immunological protection, as the Covid-19 National Task Force has also pointed out in a reportExternal link. However, being able to determine the immunity of individuals would help predict a serious course of the disease.

More

Why we still can’t test for Covid-19 immunity

And it would help prepare for possible vaccination in the autumn. “It is important to monitor the severe courses, mutations and immunity of the population against the different variants of the virus” saidExternal link University of Zurich immunologist Christian Münz. For this reason, it is crucial to continue investing in research to monitor the evolution of Covid-19. The current geopolitical situation, however, is not conducive to collaboration on SARS-CoV-2.

China’s fist of fury

Another issue is troubling the scientific community at the moment: the increase in cases in China due to the Omicron variant. Until a few weeks ago, the country’s ‘zero tolerance’ strategy, although rather extreme, seemed to be working. The economy also benefited, growing by 10.5%, compared with 2.4% in the United States and 0.4% in the rest of the developed world.

Now the new wave is testing the Beijing government and proving that this model is not sustainable in the long term. The natural immunity of the Chinese population, which is put under lock and key at the first sneeze, is in fact very low, and vaccination immunity is not among the best, due to the low effectiveness of national vaccines, as Beijing itself has admittedExternal link.

In addition, the rate of people over 80 years old vaccinated with two doses is very low in China (51%). This situation is not good news for everyone else either: China has a population of more than a billion people and too high a circulation of the virus among non-immunised individuals could cause new mutations and many deaths.

Vaccine equity still far away

This brings us to another, no less important issue: the fair distribution of vaccines. At present, 34% of the world’s populationExternal link are still waiting to receive their first Covid jab and only 59% are double-vaccinated. Switzerland is helping to bridge this gap by donating 15 million doses of coronavirus vaccine to the COVAX initiative. But the “generosity” of individual countries is not enough.

More

Covid vaccines: how to end the wait for billions of people

To really change the situation, the vaccine production plan would have to be changed, creating a network of low-population countries – such as Switzerland (which already produces Moderna‘s jabs), Rwanda, New Zealand and Singapore – which could manufacture doses quickly, both for their own populations and for the rest of the world.

“I think this is the only way around the inevitable nationalism of giving vaccines to your own citizens first,” said Britain’s Jeremy Farrar, director of the Wellcome Trust, one of the world’s largest medical research foundations, in a podcast. Let’s hope these words don’t go unheeded as well.

Do you have any comments, remarks or questions about the latest news from the world of science? Let’s talk about it over a (virtual) coffee.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.