Lady with torch leads American invasion of Locarno Film Festival

Ehsan Khoshbakht, a London-based Iranian film critic, is curating one of Locarno’s highlights: a retrospective of Columbia Pictures classics from the 1930s to the late 1950s. In an interview, Khoshbakht explains the challenges and joys of this cross-cultural tour de force.

The Locarno Film Festival is one of the most fertile platforms for discovering new talents, but it’s also consistently been one of the top venues for exploring the history of cinema. Each year, Locarno’s “Retrospective” section concentrates on a specific theme, such as national cinemas, genres or auteurs.

Mexican Popular Cinema of the 1940s and 1950s; Douglas Sirk, the master of melodrama; milestone Black films across continents – these are just a few of the most recent retrospectives screened in Locarno, and which later toured several countries.

This year’s attendees are in for a treat with a 40-film retrospectiveExternal link of Columbia Pictures, “The Lady with the Torch”, organised in partnership with the Cinémathèque Suisse.

Born in 1981 in Iran, Khoshbakht grew up during the Islamic Republic’s most trenchant period of censorship of the arts. As a burgeoning cinephile before the era of the internet, computers and pirating sites, the only way to feed his hunger for films was through an underground network who kept the art of light alive in dark times. This story is explored in Khoshbakht’s latest documentary film, Celluloid UndergroundExternal link, which premiered at the London Film Festival last year.

Khoshbakht is one of the directors and main programmers of Bologna’s Il Cinema Ritrovato, a unique festival exclusively focused on the history of cinema. For this year’s edition of Ritrovato, he put together an eye-opening retrospective of the Kyiv-born director Anatole Litvak, who made films in France, Germany and Hollywood between the 1930s and 1970s.

In 2023, Khoshbakht curated the most comprehensive programme of pre-revolutionary Iranian cinema for the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York.

In addition to his programming work, he is the author of several Persian language books on topics including Western films, classical Hollywood cinema, and film and architecture.

SWI swissinfo.ch: Do you have any notable memories of Columbia films from your childhood?

Ehsan Khoshbakht: Columbia was one of the first studios to enter the television business. In the 1950s, a generation of people who had not seen the films of the 1930s and 1940s started watching the Three Stooges on television, which suddenly became a cult phenomenon. Their films were always short, around 15 minutes.

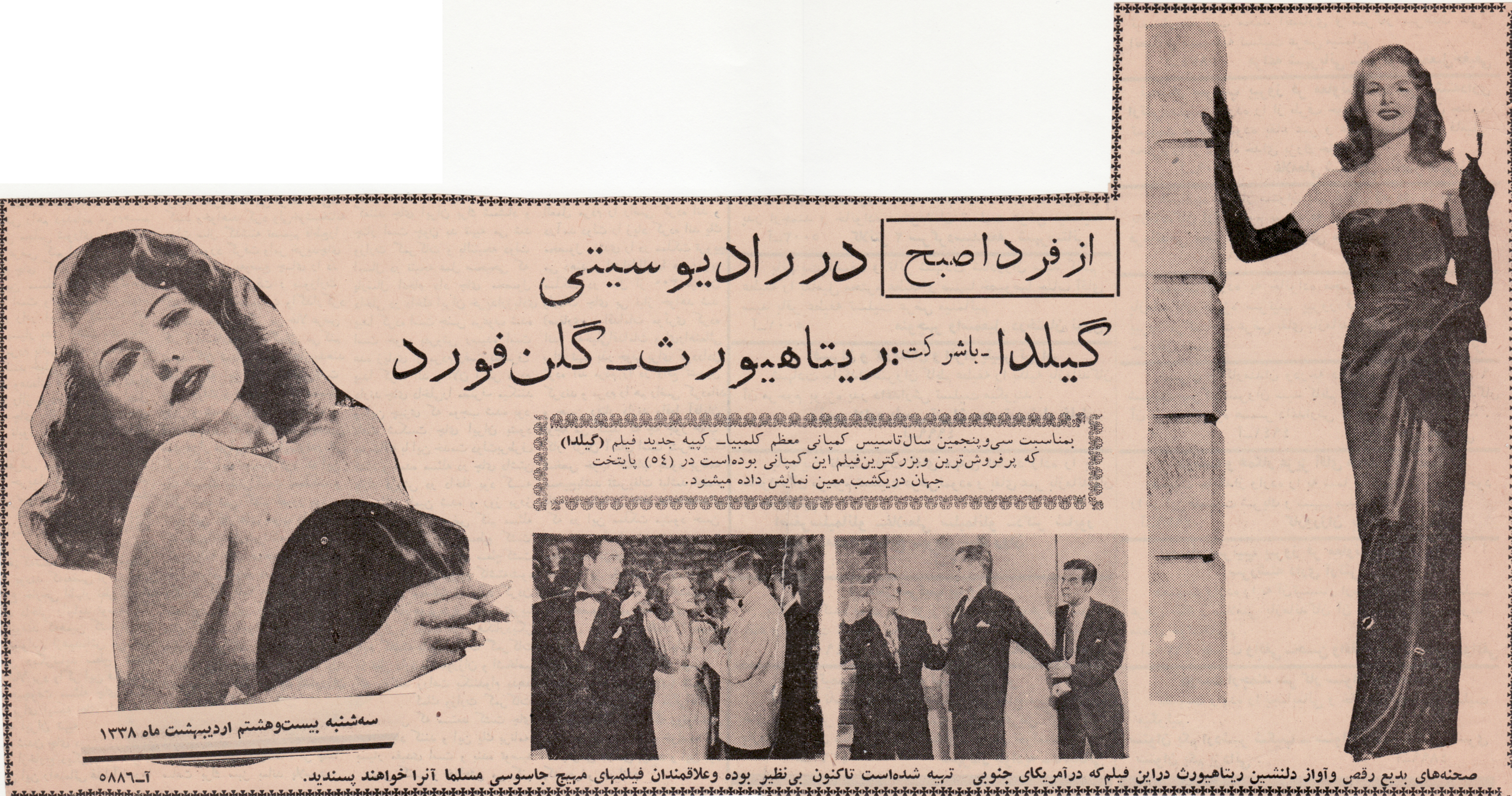

In the 1950s they started making features with them to bank on this new-found success. And the first Columbia Pictures film I saw was one of these Three Stooges films, Have Rocket, Will Travel, on Iranian television. It is a sci-fi film with a scene with a giant spider chasing the Stooges on the moon. It left its mark on me! I had been an enormous Glenn Ford fan since I was a teenager, and later on, I realised he’s heavily associated with Columbia.

SWI: What factors set Columbia Pictures apart from the other Hollywood studios?

E.K.: The studio system was based on lengthy contracts, usually around seven years, through which various workers, especially stars treated like workhorses, would be tied down and exploited.

However, Columbia didn’t have these long contracts since they didn’t want to take any risks by hiring someone for a long period who may fall out of favour with the public. Instead, they essentially became a studio of “freelancers”. This meant they had different voices, talents, and visions, constantly dropping in and out.

Perhaps the downside of this was a sense of eclecticism, as the studio didn’t develop a signature style like bigger rivals such as Warner Brothers or MGM. While Columbia is not categorised among the five “major” Hollywood studios, it wasn’t exactly a poor B-movie studio either, but it stood somewhere in between and did things in a way completely different from other studios, rich or poor.

Columbia had fascinating variations that both correspond to the broader definitions of the studio system and, at the same time, divert from them.

SWI: Can you talk about Columbia’s humble beginnings in the late 1910s and the 1920s?

E.K.: The studio started with very little means, and it grew in a very cautious and discreet manner. From the late 1920s up to the late 1930s the success and prestige of Columbia is associated with just one name: Frank CapraExternal link.

This was very unusual for Hollywood studios because each had many directors they could rely on. However, with Columbia it was about finding the right stars or directors and banking on them without risking having too many names and faces simultaneously.

After they discovered Rita Hayworth, there was little attempt to find other talents besides her. Other stars were born organically or cultivated after Hayworth started to do poorly at the box office.

Also, the budgeting at Columbia was very different from other studios. The budget of a so-called “A” picture at Columbia was closer to that of a “B” movie at major studios like MGM. They deliberately avoided certain types of films that needed higher budgets, like musicals, of which they did very few, and when they did, they had to see internal talents such as composers, choreographers and dancers.

In dodging these production challenges, their focus became the story: any story that could be told in three rooms was Columbia’s cup of tea. They were the masters of “three-room films”. Gradually, they became more ambitious with the success of earlier films, especially after Capra won the Oscars in the 1930s.

This growth in confidence continued until the final year included for this programme, 1959. But they went on making major box office hits even after that year.

SWI: What was your process for selecting the films for this programme?

E.K.: I printed the entire release schedule of Columbia Pictures from 1929 to 1959 and started watching as many films as possible. I watched at least one title per release month because patterns emerge there. I also made sure all the major stars and genres were covered in this process.

After creating my list of what could be representative of Columbia, I had to decide which ones to leave out. I had to create categories and make sure I’d seen enough films from each: films by directors who made more than a certain number of films in the studio (like Roy William Neill), absolute classics, and underseen films by great directors, great obscure films and finally, films with or about women.

The latter was one of the greatest things about Columbia. Ironically, the studio that had the misogynist Harry Cohen at the top was, at the same time, fertile ground for many female talents as producers, writers, and at least one director, Dorothy Arzner. Virginia Van Upp, the first female executive producer in Hollywood’s history, was appointed in Columbia. And she produced Gilda!

SWI: What makes Locarno the ideal festival to host this retrospective?

E.K.: First of all, it’s a question of resources. Not many festivals are capable of or willing to host major retrospectives. In a way, Locarno is the only major festival in the world that can still host large-scale events like this: showing films through the best available element (including many 35mm prints), publishing a book of original essays, and maintaining a certain quality throughout.

I was reading a book of interviews with the late Michel Ciment, one of the editors of [cinema magazine] PositifExternal link, who was telling a story about when he was on the Locarno jury with [Iranian director] Abbas Kiarostami: they used to watch films by Yasujirō OzuExternal link in the morning, which I guess was the subject of that year’s retrospective, and watch the films they had to judge in the afternoon. This combination, which simultaneously makes cinema’s past and present available for audiences to move between, is the key to the success of any film festival, even though most of them completely ignore it.

SWI: Your new film, the documentary Celluloid Underground, was just released. What’s the dynamic between your work as a curator and a filmmaker?

E.K.: I make films about films and subjects that I can’t screen; either the films have been made about them, or they are not accessible. So, my filmmaking is an extension of my work as a curator – to fill in the gaps. My first film, Filmfarsi (see trailer below), was about Iranian pre-revolutionary popular cinema whose films are now banned. Same with Celluloid Underground. It’s the story of how the ban on foreign films after the revolution affected my way of cinephilia.

Edited by Eduardo Simantob/ts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.