An ‘affront’: researchers react to the Bührle Collection in the Kunsthaus Zürich

“An affront to potential victims of looted goods”: the Bührle collection and Kunsthaus Zurich face mounting pressure from organisations and researchers.

Zurich and its Kunsthaus face mounting pressure over a controversial art collection on display in the museum after members of an independent panel of historians described the situation there as an insult to victims of Nazi looting.

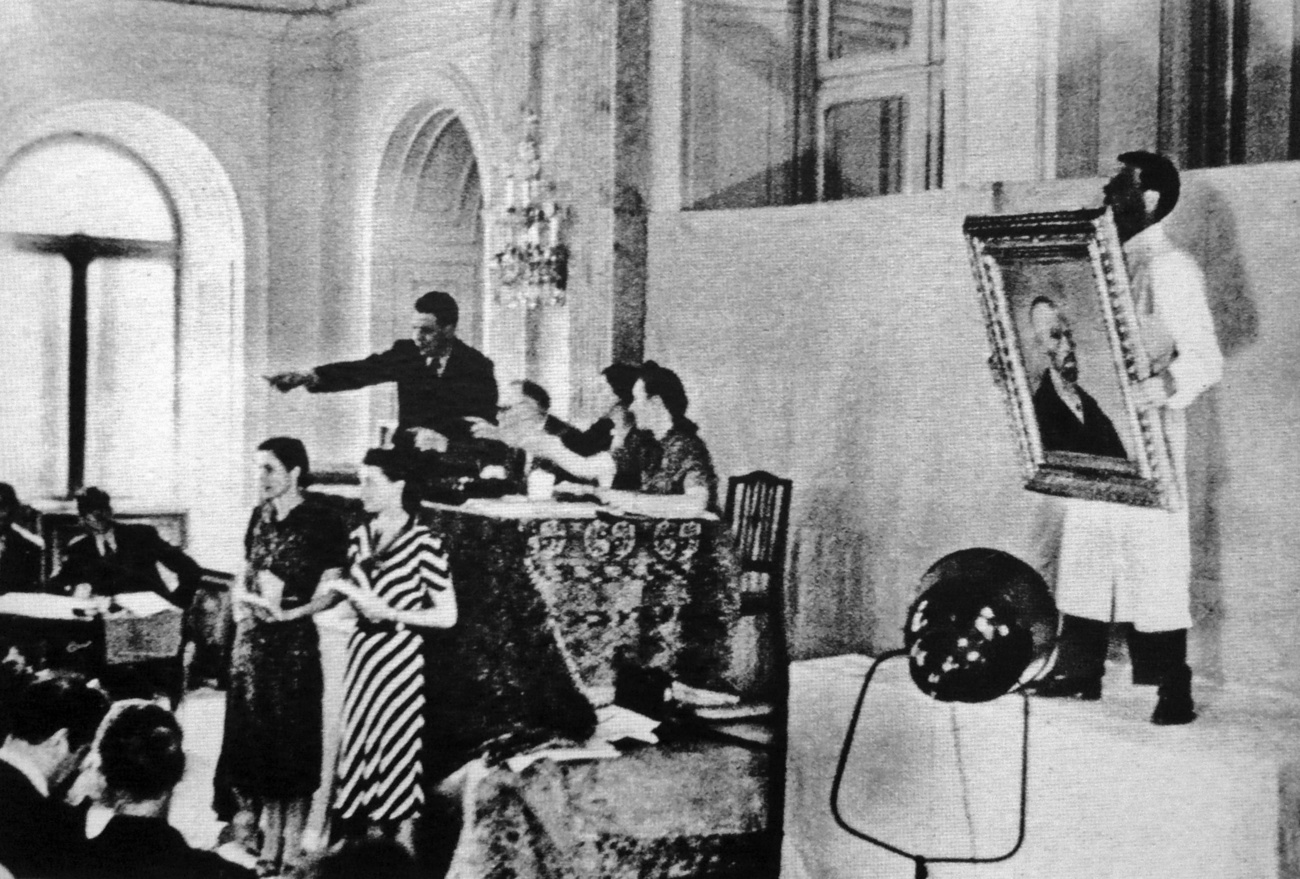

The Kunsthaus opened a new extension in October, in part to house about 200 artworks on loan from the collection of Emil Georg Bührle, who made his fortune by selling arms to Germany during World War II, bought art that was looted by the Nazis, and profited from slave labour.

The decision to show Bührle’s collection – including some paintings whose ownership is contested – has been widely attacked in the press and in a new book by Erich Keller, “Das kontaminierte Museum” (The Contaminated Museum).

Now, nearly 20 years after their investigation into Switzerland’s financial dealings during World War II was published, former members of the “Bergier commission” have added their voices to the chorus of condemnation, posing anew the question of whether Switzerland has done enough to address its complicity with Nazi crimes. The commission was set up by the government in 1996 in response to international outrage over Jewish assets hidden in bank vaults and accounts and the country’s unexamined role in bank-rolling Nazi Germany.

“The current situation in Zurich is an affront to potential victims,” said the November 7 statement from former panel members including UCLA professor emeritus Saul Friedländer and Princeton history professor Harold James.

The experts issued three demands: they called on the city and canton of Zurich to conduct an independent evaluation of the Bührle Foundation’s research into the origins of artworks in the collection; they urged the Kunsthaus to commission independent experts to revise its documentation of the Bührle collection on display in the museum, and they called on the federal government to establish an independent body to mediate between claimants and private collectors or museums on artworks that may have been lost due to Nazi persecution.

More

Zurich art museum succumbs to Bührle’s ambitions

“Why does Switzerland not have an independent entity, as many other countries do, that works to find a just and fair solution for all parties in disputed property issues?” the commission members asked.

Corine Mauch, the mayor of Zurich, welcomed the commission members’ statement as an “important contribution to an important debate.” She said the city is exploring ways to ensure an independent evaluation of the Bührle Foundation’s provenance research. The third demand, for the creation of a national panel to evaluate claims, requires “an important step on a federal level,” she noted.

Lacking institutions for problems with Nazi-looted Art

Along with more than 40 other countries, Switzerland endorsed the non-binding Washington Principles on Nazi-looted art in 1998. Under these principles, governments agreed to encourage museums to conduct provenance research, identify art seized by the Nazis, and seek “just and fair solutions” with the original Jewish collectors and their heirs on works lost due to persecution.

They also agreed to establish “alternative dispute resolution mechanisms for resolving ownership issues.” Five European countries have since set up independent panels to adjudicate claims: Germany, Austria, France, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. But Switzerland, which served as a hub for Nazi-looted art before and during World War II, has never done so.

“In Switzerland there have only been a few individual contentious cases in this area,” said Benno Widmer, the head of the museums and collections department of the Federal Office for Culture. “It is above all the responsibility of those involved to find a fair and just solution in line with the Washington Principles.” Widmer added that “if the need intensifies due to an increasing number of contentious cases, then the demand for an external commission could be re-examined.”

Some Swiss museums have reached settlements with the heirs of collectors whose art was looted by the Nazis or sold under duress. The Kunstmuseum Bern, which inherited the controversial collection of the reclusive hoarder Cornelius Gurlitt, has returned several works to descendants of the original owners.

The Basel Kunstmuseum agreed last year to pay compensation to the heirs of Curt Glaser, a renowned Jewish museum director and critic who sold his collection before fleeing Nazi Germany. This was a reversal of its position in 2008, when the museum had rejected the heirs’ claim, arguing that it had purchased the works in good faith and Glaser had received market prices.

But the Glaser claim and others may have been resolved more quickly by a neutral panel, says Thomas Buomberger, a historian and author of a book about the Bührle collection, “Schwarzbuch Bührle” (Bührle Black Book). “It’s a disgrace that a panel was never set up – a total failure,” Buomberger says. “But I don’t think it’s too late. Perhaps this discussion will give the necessary impetus.”

The absence of an independent body to assess claims “makes life much harder for the claimants,” said Thomas Sandkühler, a professor of history at the Humboldt University in Berlin and a former member of the Bergier Commission who signed the statement. “They have nowhere to turn.”

Juan Carlos Emden, for instance, first laid claim to Claude Monet’s 1880 “Poppy Field Near Vétheuil” in the Bührle collection about a decade ago. He says that his father, Hans Erich Emden, sold it as a result of persecution by the Nazis. Hans Erich Emden was the son of a German Jewish department-store mogul whose assets in Germany were seized by the Nazis after he emigrated to Switzerland.

But the Bührle Foundation rejects Emden’s claim, arguing that the sale was not made under duress. Filing suit in court is futile because of statutes of limitation and other technical hurdles to ownership disputes dating back decades. So Emden has no recourse to an independent judgment.

“It is a mystery to me how the people managing the estate of an arms dealer can presume to judge whether or not my family sold this painting under duress,” says Emden, who lives in Chile.

Disappeared Documents

The Bergier commission’s members appeared particularly irritated that the Bührle family told what they describe as an “untruth” about its files. The Swiss government accorded the commission sweeping powers to access private and corporate archives in its quest to trace gold, currency, and cultural property that may have been immorally acquired.

But when commission members approached the Bührle family for access to its archive, the response was that “there were no more files that could be made available,” the commission members said in their statement. Since then, comprehensive archives have emerged.

The Swiss historian Georg Kreis, a former member of the Bergier Commission, said he visited a Bührle family member who told him there were no records except for one small box of index cards. “I remember wondering whether to ask the police or prosecutor to conduct a house search, but I thought that if there were any files, they would have got rid of them,” Kreis said.

Lukas Gloor, the director of the Bührle Foundation, said these events occurred before he took office and declined to comment on them. He pointed out that the foundation has published the provenance research on its website and that the archives are now accessible to independent researchers at the Zurich Kunsthaus. “There is nothing standing in the way of deeper research from the point of view of the Emil Bührle collection,” he said.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.