An artefact returns to Namibia from Switzerland

In the Nambian coastal town of Swakopmund, traces of the German colonial past are everywhere. But the only place dedicated to the genocide against the Herero is the Genocide Museum, on the outskirts of town. An artefact from Switzerland is also on display there.

The Swakopmund Genocide Museum covers an area of about 12 square metres. Laidlaw Peringanda, an artist and Herero activist, welcomes visitors from a small office table.

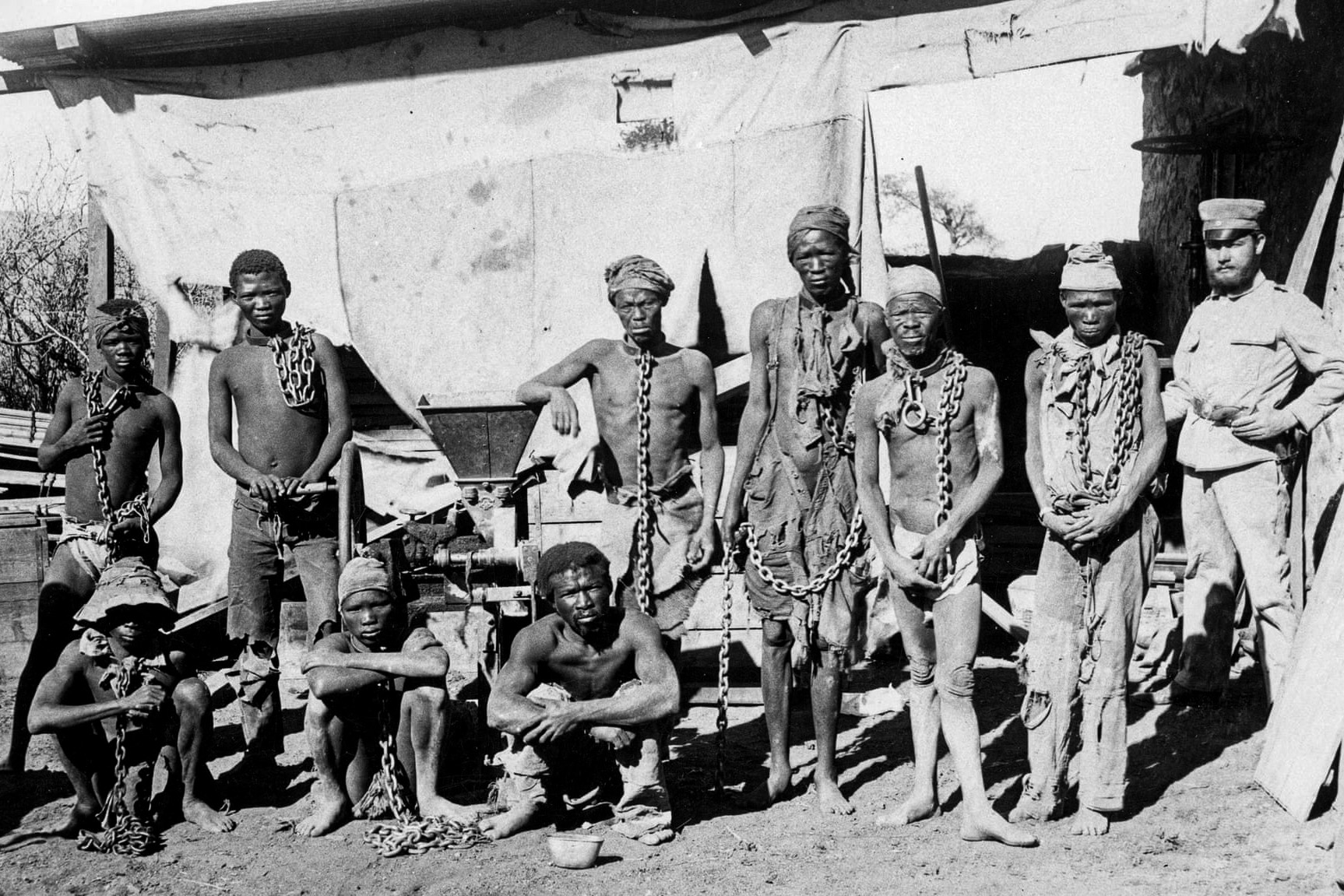

In front of him are a laptop and an array of books and magazines on the subject. The photos on the walls bear witness to the deeds of the German soldiers: severed heads, emaciated men in chains, skulls stacked in piles.

The first genocide of the 20th century

Between 1904 and 1908, the troops of the German Empire murdered up to 100,000 Herero and Nama people in the former colony of German South West Africa by putting them in concentration camps or driving them into the desert.

In Swakopmund, apart from the Genocide Museum, there is almost no discussion of these events. The city is still strongly influenced by the language and culture of the German colonial power.

For many years, Peringanda has been campaigning against repression and denial at his museum in a township on the outskirts of the city, where a large proportion of the black population lives in poverty.

One focus of his work is to trace and repatriate artefacts and human remains from his people, the Herero, a Bantu ethnic group inhabiting present-day Namibia.“They are scattered all over the world, in museums and private collections,” he says.

Human remains from Namibia can still be found in various Swiss institutions. In Zurich, for example, they were the focal point of research by a Swiss student of Namibian origin.

The woman from Zurich who inherited a Herero headdress

In rare cases, private individuals also approach Peringanda directly to return items. For example, Katharina Küng from canton Zurich had a headdress that she had received from her mother hanging on her wall for a long time. “We thought it was the padding of an old suit of armour,” Küng says.

It wasn’t until a trip to Namibia that she realised – in Peringanda’s museum – that it was a traditional Herero headdress. Before colonisation, married women wore it on special occasions. During German colonisation, missionaries forced the population into European dress.

Back in Switzerland, Küng decided that the headdress had to go back. However, as she had no documents and hardly any other information, she didn’t dare bring the artefact to Namibia herself: “I was afraid of doing something illegal – what if I was arrested while crossing the border?”

Küng contacted Peringanda via the internet and together they decided on the safest method for both parties: the headdress was sent by post. Today it hangs in Peringanda’s museum in Swakopmund.

But how did it end up on Küng’s wall in the first place? “My mother worked as a cleaner, she cleaned rich people’s houses,” says Küng. The headdress must have come from such a house, but she was unable to find out exactly to whom it belonged. Her mother has been dead for a long time and so have the people for whom she worked.

More

Artefacts held in Swiss private collection return to Latin America

During the colonial era, Swiss people also settled in Namibia. According to Dag Henrichsen, a Namibian researcher at the University of Basel, they worked as farmers, traders, craftsmen and engineers.

Legal disputes over restitution

Küng’s willingness to return cultural patrimony is an exception. Peringanda from the Genocide Museum in Swakopmund is embroiled in legal disputes with museums such as the American Museum of Natural History in New York. They refuse to hand over artefacts and human remains from Namibia. He receives death threats from some German-Namibians.

The Swakopmund town council also puts obstacles in Peringada’s way. It fears for the city’s image among tourists. Nevertheless, he continues his work – within and outside the small museum.

At the cemetery that morning, Peringanda welcomed a tour group from Germany. Together, they walked past the lovingly tended graves with European names to the back of the cemetery.

Hundreds of small mounds cover the sandy ground here. Some are decorated with piled stones, a few are marked with wooden crosses. Graves stretch as far as the eye can see.

More

Culture stories by SWI swissinfo.ch

‘Colonial amnesia’ in Swakopmund

The only inscription for miles around adorns the large black memorial stone that separates the European and African parts of the cemetery. Here, Peringanda tells the story of the unknown number of Nama and Herero who died during their captivity between 1904 and 1908: from hunger, slave labour, sexual violence, disease and exhaustion.

Henrichsen says that in addition to people who died in concentration camps, the Swakopmund graves contain the bodies of contract workers who died of cold, typhus and scurvy, including Ovambo people from the north of the country and Damara people from central Namibia, as well as men from the British colonies in West and South Africa. Several hundred victims of the Spanish flu were added in 1918 and1919. What they all had in common was that they were African forced labourers for the settler colony.

Bernd Heyl, a tour guide, is also committed to a critical approach to the past. For 16 years, he has been organising study trips to Namibia that are recognised by the ministry of culture in the German state of Hesse as professional training for teachers, and he has written a post-colonial travel guide on German colonial historyExternal link. However, most tourists in Namibia are unaware of this. Heyl says there is “colonial amnesia”.

He wrote the book “so that it would stand next to all the other books on the shelf”. Heyl mentions “reactionary books glorifying colonialism” in Swakopmund bookshops.

The town of 76,000 inhabitants presents an idyllic showcase of the colonial era – with Art Nouveau facades, Wilhelmine gables and German street names. The misery of the past remains hidden.

How did Namibia become a German colony?

In 1884, Germany proclaimed Namibia its first colony: German South West Africa. As the colony’s most important port city, Swakopmund was the gateway for German settlers and soldiers. While the Germans built farms, the locals were demoted to second-class citizens, dispossessed and disenfranchised.

When resistance increased in January 1904 and 100 German settlers were killed, the empire reacted with genocidal violence.

The much larger local museum in Swakopmund offers a stark contrast to the Genocide Museum. The shop sells the books to which Heyl alluded: Heisse Tage – Meine Erlebnisse im Kampf gegen die Hereros (Hot Days – My Experiences in the Battle Against the Hereros) or Soldatenleben…Erlebnisse als hessischer Kanonier in Lotheringen und Deutsch Südwestafrika (The Life of a Soldier… Experiences of a Gunner from Hesse in Lotheringen and German South West Africa”). Abundant uniforms of the imperial army, military insignia, and weapons of all kinds are on display in this local history museum.

Years of tough negotiations between the German and Namibian governments led to a highly controversial joint declarationExternal link in June 2021, which has not yet been ratified and has met with considerable resistance in Namibia. In it, the German government recognises that the events of that time “can be described as genocide from today’s perspective”. It sees a “moral, historical and political obligation” to apologise for the genocide. Legal responsibility is deliberately excludedExternal link. Instead of reparations, Germany wants to pay €1.1 billion (CHF 1.03 billion) in reconstruction aid over a period of 30 years.

UN special rapporteurs have criticisedExternal link the failure to directly include Herero and Nama communities in the negotiations and have urged the German government to pay reparationsExternal link.

But anyone who wants to find out more about the genocide has to look hard. In an abandoned conference room at the back of the local history museum, a few panels with information about what is described as the “dark period” between 1904 and 1908 have been on show since an exhibition in 2022.

Times are changing in Swakopmund

Time has not left Swakopmund untouched. The naval memorial in the town centre, which commemorates the German soldiers who died in the fight against the “rebellious Herero”, is smeared with red paint.

Kaiser-Wilhelm-Strasse is now called Sam Nujoma Avenue, after the first president of the young republic.

But the young people who help Peringanda restore the graves in the cemetery four times a year represent the changing times. According to him, they include many young German-Namibians. They declined to comment on their activities to SWI swissinfo.ch.

To this day, collections from Namibia can still be found in Swiss museums.

The Bern Historical Museum houses the 1906 collection of Victor and Marie Solioz, a couple from Bern and the Jura. As chief engineer of the Otavi Railway, Victor Solioz was involved in building the German Empire’s colonial infrastructure in what is now Namibia. How the couple managed to acquire hundreds of objects in the middle of the war and ship them to Europe is still unclear today.

The collection is the subject of a museum partnership, Usakos – Making of Common HistoryExternal link, between the museum and descendants of the community of origin. The objects are to be returned to their place of origin by 2026.

The most extensive ethnographic collection from pre-colonial Namibia can be found in the Ethnographic Museum of the University of Zurich. It was accumulated by the Zurich botanist Hans Schinz on his travels between 1884 and 1886. In a press releaseExternal link, the museum wrote that it faces the challenge of finding “an appropriate and ethically justifiable way” to handle the objects in the collection.

Edited by Benjamin von Wyl; translated by Catherine Hickley/ds

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.