Anti-Semitism in the Swiss left – still a taboo?

Anti-Semitism is widespread in Swiss society, even within the political left. How do Jewish people, historians and activists perceive the way anti-Semitism manifests itself in leftist circles?

When Amir Malcus takes his baby out for a stroll in the pram, he walks past a leftist bar. A sign in front of it says: we don’t tolerate racism, sexism, homophobia and any other kind of discrimination. Anti-Semitism is not on the list.

“This is typical left!” the 37-year-old social worker thinks to himself.

Malcus was politically active. No longer. “It was very disillusioning to experience how rampant anti-Semitism was in the part of society I had the highest hopes in,” he explains.

To find out how anti-Semitism is perceived in left-wing political circles, SWI swissinfo.ch spoke to Swiss Jewish people, historians and activists who consider themselves to be on the left of the political spectrum.

In Switzerland, anti-Semitic prejudices repeatedly rise to the surface. An example is the discussions 25 years ago about the dormant assets of Jewish Holocaust victims, Nazi gold in Swiss banks and Swiss refugee policy during the Second World War, which was characterised by a fear of “Judaisation”.

While the government of the day reluctantly agreed to pay compensation for the lost assets, almost half of the Swiss population wanted to reject all claims, according to a poll by the public broadcaster, SRF. Anti-Semitic stereotypes were regularly used as arguments in letters to newspapers. The Federal Commission on Racism noted a total lack of inhibition when it came to making anti-Semitic statements.

Where did these ideas come from? In a four-part series, SWI swissinfo.ch explores the role anti-Semitism played in Switzerland before, during and after the Second World War.

Although anti-Semitism was part of everyday life in the conservative valley of German-speaking Switzerland where Malcus grew up, he says he succeeded in educating a small group of his friends that not all Jewish people were rich. This helped dispel some of the other stereotypical, anti-Semitic notions held by his peers, with whom he used to squat houses. When he ventured out of the valley and addressed global issues as inequality and exploitation, he realised that anti-Semitism was not only rife in his community. At political gatherings, he regularly witnessed hostilities being expressed towards Israel.

“Slogans like ‘We will burn down your country’ were not directed at me, but I heard them,” says Malcus.

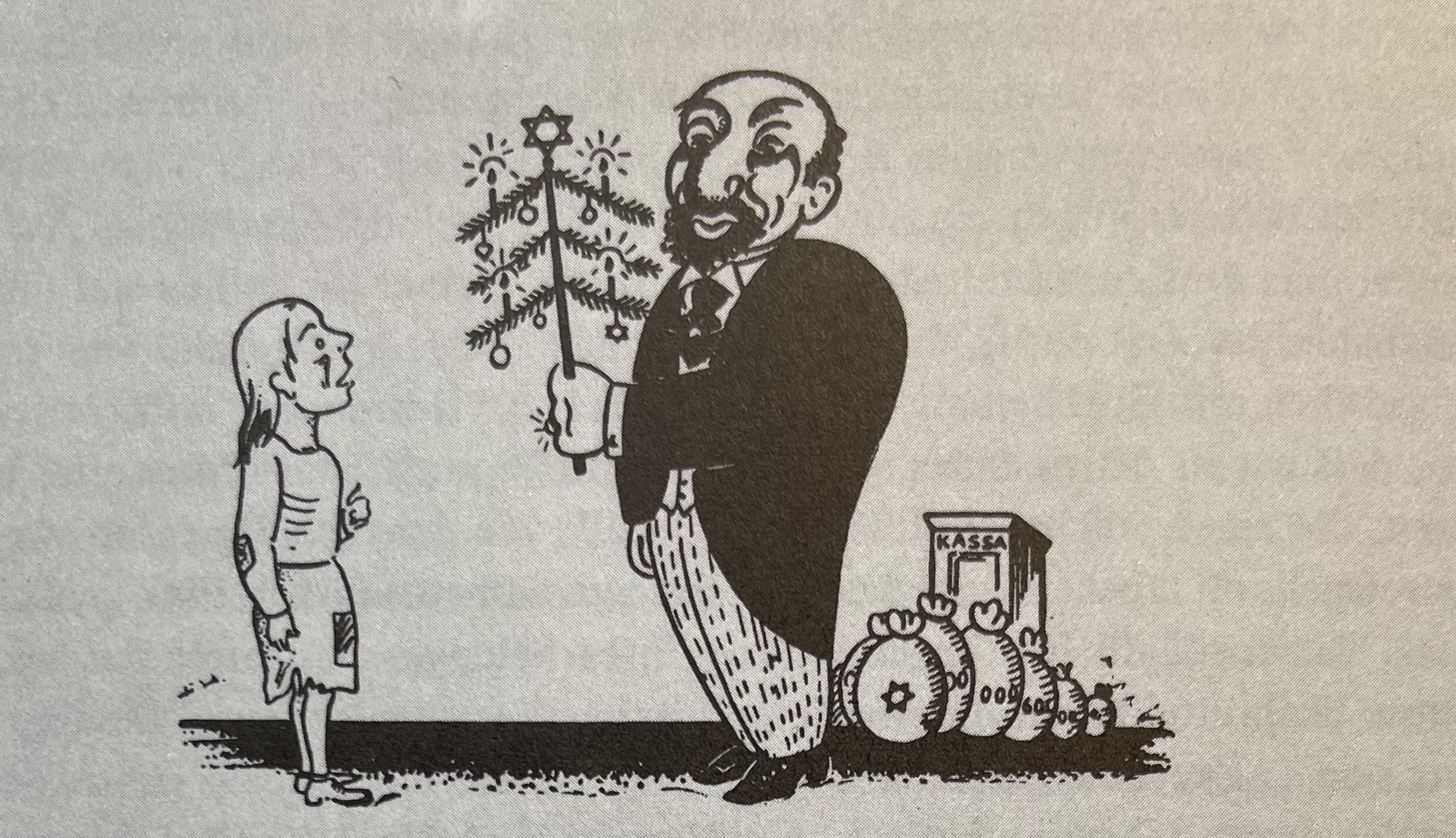

At demonstrations against the war in Iraq or the World Economic Forum in Davos, Malcus was perturbed by the demeaning cartoons of capitalists that were used on banners as they reminded him of how anti-Semitic caricatures were used against Jews in the past: puppet-masters pulling the strings from behind the scenes. A good example of this occurred 2016 when the youth section of the Social Democratic Party published a cartoon of a lobbyist for the financial market with a big nose, a cylinder hat and side curls to protest against food speculation.

“Anti-Semitism is a master of metamorphosis,” says Dina Wyler, managing director of the Foundation against Racism and Anti-Semitism. “It adapts to the current narrative and often comes to the surface by way of images or buzzwords. In this way it remains ‘socially acceptable’”

Demonising Israel

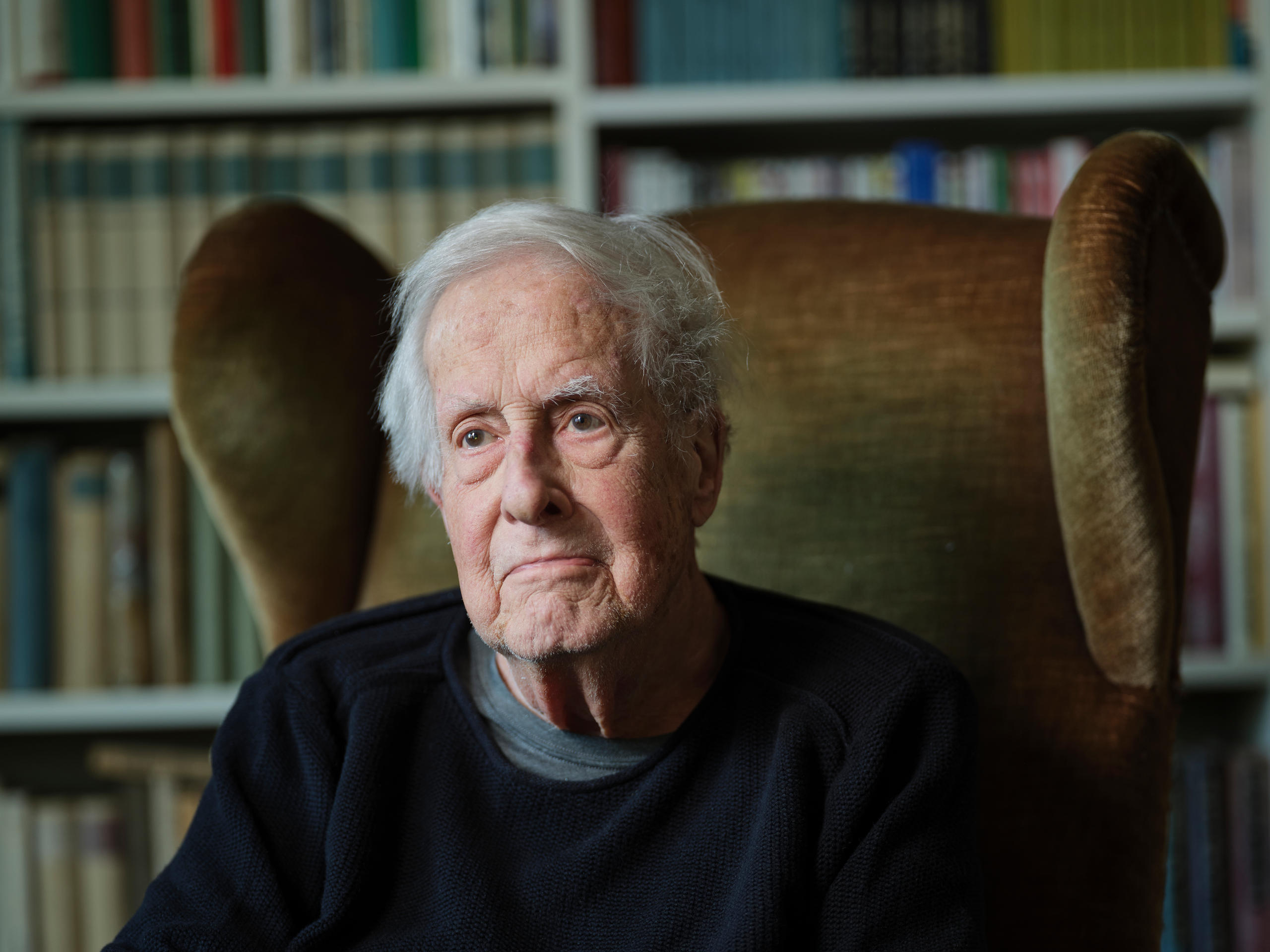

The antagonism against Israel Malcus experienced among the left in the 2000s is not new. It has been around for decades. During his childhood in Zurich during the Second World War, Swiss psychoanalyst and politician Emanuel Hurwitz was pelted with stones by other children who yelled anti-Semitic insults at him.

“I never experienced such open anti-Semitism later on among left-wing circles,” Hurwitz told SWI in an interview before he passed away aged 86 in February. After he graduated from university, Hurwitz got involved with the Social Democratic Party. He was elected to Zurich’s cantonal parliament and became a left-wing politician. Hurwitz felt that his party’s stance on the Middle East conflict in the 1970s was in line with his views.

However, this changed with the start of the Lebanon war during which Israel was the aggressor. “From 1982 onwards, the Social Democratic Party was in turmoil,” Hurwitz remembered. He said he joined countless panel discussions as a Jewish left-wing representative. “Many of these debates turned out to be propaganda events for the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO),” he said. Hurwitz noticed a certain pattern in the arguments: Israel was portrayed as evil while the PLO was hailed as the hero.

Hurwitz said he was surprised by the hate and fanatism that erupted during these discussions and his only explanation for the demonising allegations against the Jews was anti-Semitism. As a psychiatrist, he tried to explain to his peers how an ancient tradition of anti-Semitic prejudices could resurface in a politically charged situation, but to no avail.

On May 1, 1984, Hurwitz was so disillusioned with his party’s policies that he resigned from parliament and the party. After his resignation, the Zurich-wing of the Social Democrats promised to talk things over with him. This discussion never happened, he said. But when in 2019 the Social Democratic Party adopted the working definition for anti-Semitism used by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA), which also included anti-Israel hostilities, it meant a lot to Hurwitz. Finally, his peers had showed some understanding.

Anti-Semitic tropes

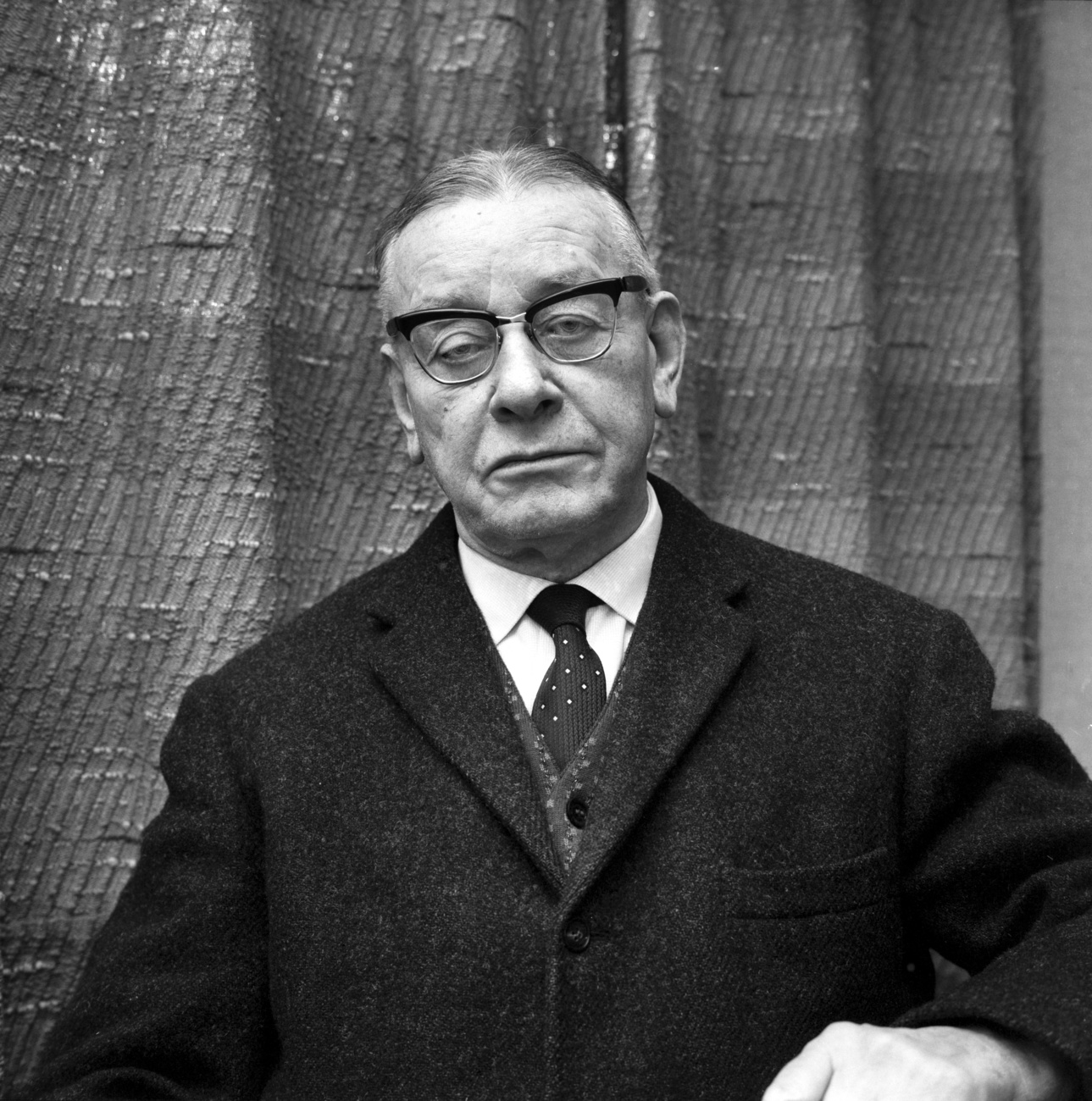

Hurwitz’s long-time friend Berthold Rothschild, who was a member of the Swiss Workers Party (PdA) in the 1980s, explained that the communists considered Israel as a “heroic nation in its infancy” for a long time.

“But suddenly, this attitude changed,” Rothschild said. When more and more communists started to make stereotypical allegations against Jewish people, such as accusing them of betraying the left, he walked away from his party. This was around the same time when Hurwitz left the Social Democrats.

Rothschild also talked about the emotional rollercoaster he experienced when it came to Israel-Palestine relations. “Some very good friends of mine turned a blind eye to the fact that Hezbollah and Hamas simply hated the Jews,” he says. “I always wanted to maintain these friendships but there have been times when I had to get up and leave… At the same time, I understand that Israel’s politics and the way the government treats the Palestinians upsets many left-wingers, which is often justified.”

One of Rothschild’s friends advocates for the Palestinian cause in Gaza. “I understand that people become pro-Palestinian and anti-Israeli when they experience first-hand what is happening on the ground,” he says. Being against Israel’s policies towards the Palestinians is not the same as being anti-Semitic, but Rothschild thinks it is not far off.

“Anti-Semitism among the left is unresolved, denied and repressed,” he says. “I hope that people are aware of their anti-Semitic traits as much as I am aware of the racism I adopted from society.”

Pro-Palestinian activists must be extremely careful to avoid coded anti-Semitic language, he adds. And indeed, some of his leftist friends are very careful about the language they use. They give him flyers or political texts to make sure they don’t contain unintentional anti-Semitic stereotypes. But this is the exception rather than the rule.

But “a toxic mix can emerge” if you don’t objectively criticize Israel’s policies and hypothesise that immoral behaviour has a direct link with Jewishness”, says Erik Petry, the deputy head of the Centre for Jewish Studies at Basel University. He has often seen some examples of this venomous mix among people on the left.

‘A slap in the face’

Swiss right-wing politicians often point out that anti-Semitism exists among the left. According to historian Christina Späti, they do this to whitewash their own flaws on that front.

“But this does not mean that there is no anti-Semitism amongst the left,” says Späti, an associate professor of contemporary history at the University of Fribourg. Her thesis focused on The Swiss left and Israel. Enthusiasm for Israel, anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism between 1967 and 1991. Späti uses sober language to analyse newspaper reports and incidents that reveal anti-Semitic sentiment in left-wing circles.

In 1970, for example, the socialist press published an opinion piece which rebuked Israel’s capture of the high-ranking Nazi official Adolf Eichmann in Buenos Aires as a “slap in the face” of Argentina. In the 1980s, Switzerland’s largest left-wing newspaper compared Israel’s policies towards Palestinians to the Nazi’s “final solution of the Jewish question” – the code name for the genocide of Jews in Europe.

Späti says the opinion piece about Eichmann’s capture stands out as one that caused outrage among the population. “The anti-Semitism in the article was simply too grotesque to go unnoticed,” she says. “There were other, more subtle incidents that did not cause such a stir. There is a certain continuity of the left’s indifference to anti-Semitism. While in the 1990s the Germans started to reflect on the events during WWII, it remained a taboo in Switzerland.”

Over the past few years, Späti has noticed a growing need among the left to address anti-Semitism within their ranks. A left-wing activist against anti-Semitism told SWI how in the 1990s men from left circles threatened to shoot her in the knee during an awareness-raising event on anti-Semitism in Zurich.

At the beginning of the 2000s, an anti-Semitic blog and cartoon on the Indymedia website was so offensive that it triggered a debate among leftists and led to a criminal charge. Even though Indymedia’s administrators found the blog anti-Semitic, they refused to take it off their website.

At the same time, the left-wing German-speaking newspaper Wochenzeitung ran an article on the blog saying that friendships became toxic in this “psychodynamics of escalation”. The article also quoted someone who oversaw the Indymedia website at the time, expressing skepticism towards “government tools to combat racism as the law against racism.”

Today, 20 years later, hardly anyone on the Swiss left would express such an opinion publicly. The feminist and anti-racist movements of recent years have raised broad awareness of discrimination issues.

Today, 20 years later, hardly anyone on the Swiss left would express such an opinion publicly. The feminist and anti-racist movements of recent years have raised broad awareness of discrimination issues.

Nevertheless, young left-wingers of Jewish origin feel how anti-Semitic patterns have come to the surface within their ranks. Anna Rosenwasser in Zurich jokes she is only half as Jewish as her name sounds. “But when it comes to anti-Semitism, I am more than half affected,” the 32-year-old journalist and LGBTQi activist says. She has 25,000 followers on Instagram, where she gives her opinion on the latest voting issues and on queer and feminist topics.

Rosenwasser perceives anti-Semitism outside left-wing circles as more menacing. The left, she believes, has set higher standards for themselves.

“It’s obvious that leftists must be careful how they address anti-Semitism,” adds Rosenwasser. “Anti-Semitic thinking patterns are deeply engrained and easily spread in our society. I think it is an important anti-fascist duty to detect them and reflect on them.”

Wyler of the Foundation against Racism and Anti-Semitism thinks many people are convinced that Jews are privileged and hence cannot be discriminated against. “The left often denies that Jewish people experience discrimination.”

Translated from German by Billi Bierling/ds

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.