Art Basel: Where have all the Russians gone?

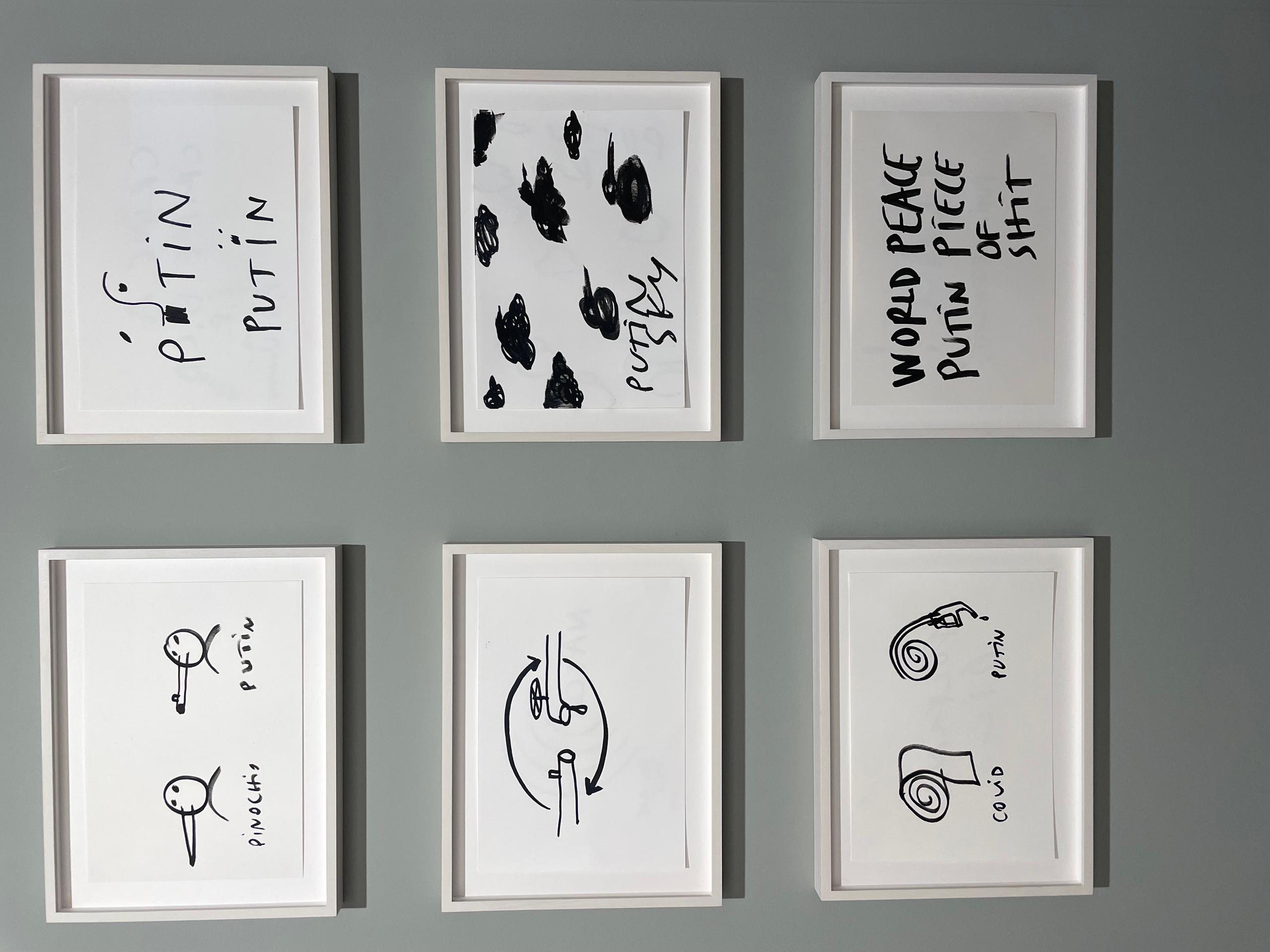

After a hiatus of three years, Art Basel returned in (almost) full form. Attendance from galleries and the public was high. But the war in Ukraine also left its mark on the fair.

The absence of Russian galleries in Art Basel, the world’s biggest art fair that finished on June 19, was quite conspicuous – although not surprising. Faced with international sanctions and the virtual impossibility of moving freely around Europe, Russian art dealers and their artwares were limited to an alternative art fair in Saint Petersburg that opened on the same days as Art Basel.

Named 1703 Contemporary Art FairExternal link, alluding to the year of foundation of the Russian imperial capital, it was sponsored by the Kremlin-linked energy giant Gazprom and counted a total of 17 galleries.

This is little compared with the 289 galleries present in Art Basel, a number which marked an almost back-to-normal atmosphere. As a comparison, last year’s pandemic-stricken Art Basel had 272 participants, and the 2019 edition counted 290. In 2020 the event was cancelled.

Russian galleries were in no way banned from attending the fair. Many were able to participate in online viewings, an also popular way of displaying artworks for sale.

At the opening of this year’s edition, Marc Spiegler, Art Basel’s global director, stressed how the fair had become more open to galleries beyond its traditional sphere of influence (the United States, Europe and Japan), notably with galleries from Africa and the Middle East. However, he did not mention Russian participation nor guidelines sanctioning Russian participants.

Gold from Moscow

While Russian galleries were never a particular highlight of the fair, Russian buyers and collectors and their hefty wallets were more of an attraction. These were still visible in the booths and corridors, whether in person or through consultants, mainly from the United States and the United Kingdom, who serve as intermediaries for biddings and acquisitions.

All through the preview days, before Art Basel opens to the public and when big sales are inked, the Russian language could still be heard inside the fair. Two prominent Russian journalists, Andrey Malakhov (presenter on the main Russian television channel, Russia-1) and the TV anchor, socialite and actress Xenia Sobchak were rumoured to have been spotted. SWI swissinfo.ch could not verify these claims.

With travel sanctions in place, most of the Russian buyers circulating in Basel this year live abroad. SWI met one by chance, who identified himself as Denis Sel, an arts trader.

He has been living and operating in Cologne, Germany, for 16 years. “There is no surprise in this [authoritarian] turn of events in Russia, we all saw it coming for quite a long time,” he says. According to him, the Russian elite who work in the arts and have decided to stay in Putin’s Russia knew exactly what was going on and accommodated themselves with those in power.

Sel, on his part, says he has nothing to do with the Russian art scene. “There are many more interesting artworks in Cologne to deal with, we have Joseph Beuys, Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke, for example. Why should I care about the Russians?” he says.

Enter the Ukrainians

Some of the empty spots left by Russian galleries were filled with those from Ukraine. A few weeks before the start of Art Basel, news spreadExternal link that Fragment and Osnova, two Russian galleries at the parallel Liste fair, had generously ceded their spaces for two Ukrainian galleries. “This is not exactly what was communicated to us,” Maria Lanko, co-owner, with Lizaveta German, of The Naked RoomExternal link gallery in Kyiv tells us. “We were directly invited by Liste. We wouldn’t want to be invited by Russian galleries anyway,” she adds.

The more realistic scenario is that the Liste organisers, probably facing a last-minute cancellation from the Russian galleries due to the Ukraine war, offered a booth to Lanko and to another Ukrainian gallery, VoloshynExternal link, for free. The booth price for a newcomer at Liste is $7,600 (CHF7,300).

Both Voloshyn and The Naked Room galleries have applied to Art Basel for years for a booth at Liste but were rejected. This year, they are some of the lucky ones able to travel despite the war.

ListeExternal link, like the other parallel Basel fair, VoltaExternal link, started as an independent space for younger gallerists, and for many years served as a fresher counterpoint to the established art traders dealing their millions of dollars in the exclusive halls of the official Art Basel. Both parallel fairs have already become intrinsic to the main event, as “alternative institutions” that serve as a springboard for galleries aiming to enter the elitist Art Basel club.

Art under siege

The situation of the Ukrainian gallerists is dire, they tell us. Maxim and Julia Voloshyn have been on the road since last Autumn. “We left for an exhibition in Mexico,” says Julia Voloshyna, “afterwards we had another one in Dallas, and when the war broke up, we were left stranded in Miami.” Meanwhile, their gallery in Kyiv has become a shelter for their friends and family.

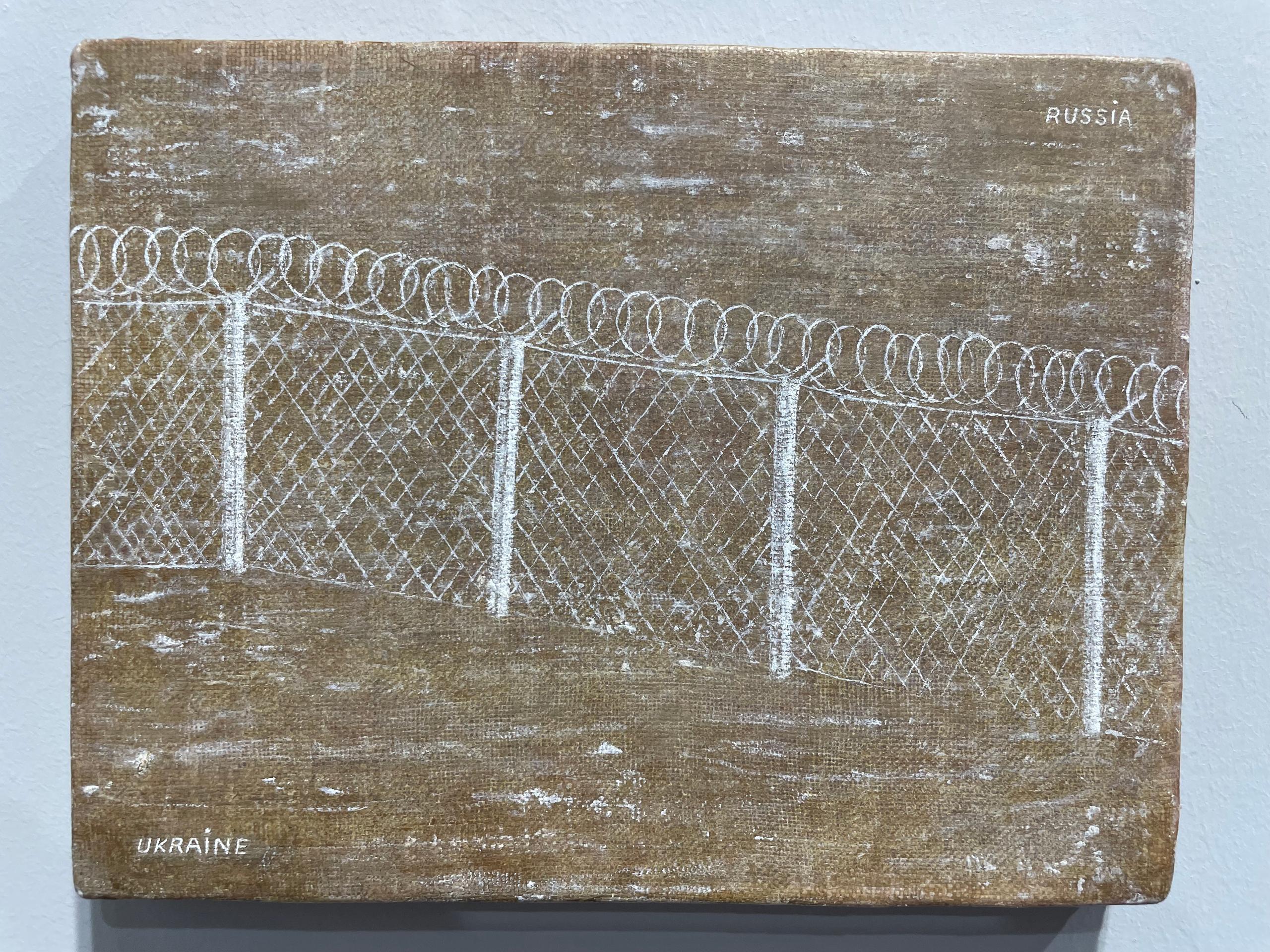

“It is sadly ironic that the building where our gallery is located was already used as a bomb shelter during the Second World War,” says Maxim. When the Russian bombs started falling in Kyiv in the freezing days of late February, Voloshyn’s artists, their families and pets, plus a few neighbours, all took cover in the gallery, which still had the heating pumps working.

The nomadic life of the Voloshyns, moving around with their 2-year-old daughter, is in no way an escape from the war. “We have to do as many art fairs as we can,” says Maxim, “because that’s how we may support our artists, our gallery, and our families in Ukraine.”

For the Ukrainian artists, the reality is much more dramatic. “They are not doing any art right now,” says Maria Lanko. “They are all helping with the war effort as soldiers, volunteers, etc.,” she adds.

But one of the main artists in the Voloshyn’s catalogue, Lesia Khomenko, did manage to complete a series in time to send it to the ongoing Venice Biennale, called Max is in the Army. Drawing on images of her husband Max, also an artist, donning a military salute, it depicts ordinary men taken away from their ordinary lives to become soldiers. Lesia has no idea where her husband is right now.

We don’t talk about Russians

The Ukrainians in Basel refused any kind of association with their Russian peers. And this estrangement didn’t start with the February war still going on – it is a long-running issue.

Maxim and Julia Voloshyn say that the Ukrainian art scene developed with completely different dynamics to the Russian one after the end of the Soviet Union. Maria Lanko’s stance is more nuanced. For her the real split happened with the Donbas conflict and the annexation of Crimea, in 2014.

“Before 2014 it was maybe not the same scene, but both were very interconnected. We were part of the same kind of cultural mind-space. Since then, we have moved so far apart. I don’t even know what’s happening in the Russian art scene anymore, I don’t know even who the new artists are there,” she says.

Some friendships endured, of course, but on an institutional level all ties were cut. Still, Russians bought her artists’ books in Basel. “They were very shy and started speaking with me in English. I think they are ashamed. They definitely should be,” she says.

Whatever the circumstances that brought the Voloshyns and Lanko to Basel, PR stunts notwithstanding, it was worth their effort. Lanko says that she made her first substantial sale ten minutes into the preview. When the fair opened to the public, most of her artworks were already sold or reserved.

Moving their artworks, though, is still tricky. In the first weeks of the war, Lanko managed to move her wares from Kyiv to a storage in a museum in Lviv, closer to Ukraine’s European borders. The Voloshyns still have most of their works in Kyiv, but to operate from the Ukrainian capital is virtually impossible.

“You have to imagine that travelling to any European city from there takes at least three days – there are no flights out of Kyiv. Artworks not only need special packaging but also permits, customs forms and a whole lot of bureaucracy,” says Maxim Voloshyn.

The war so far shows no signs of abating, but Lanko and the Voloshyns say they are prepared to brace this nomadic way of life for an indefinite time.

Edited by Virginie Mangin

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.