Art detectives mull Gurlitt treasures

After the decision by Bern’s Museum of Fine Arts to accept the Gurlitt bequest, Germany’s task force of experts is busy examining the works in the hoard to see if they were stolen by the Nazis – no easy job.

Since May 2013, the team of international experts has been analysing the provenance of artworks left behind by the late Cornelius Gurlitt. This challenge requires art history expertise, a focus on detail and a willingness to stick with the task. Christoph Schäublin, chairman of the board of the Museum of Fine Arts in BernExternal link, has no illusions about the time this will take. “We are not at the end, but at the beginning of a long road,” he said in Berlin.

If Germany is to shoulder its responsibilities for the misdeeds of the past, the researchers have to find out whether Gurlitt’s collection contains artworks stolen or looted by the Nazis – and how the pictures came into the possession of the wealthy Munich recluse’s father, the art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt.

Long road ahead

Just how tough the researchers’ task will be is shown by the modest success of the committee: just 499 of the 1,258 art objects in the Gurlitt collection are now suspected of being stolen art. That means that they may have been confiscated from Jewish owners or bought for a token price during the Nazi period.

More

Inside the Gurlitt collection

It has been decided that these works will remain in Germany until their provenance has been fully investigated. They have been displayed on lostart.deExternal link, a digital database for stolen art. So far, only three works – a Liebermann, a Matisse and a Spitzweg – have been restored to their rightful owners. For as many as half of the pictures, the researchers have only made a preliminary evaluation.

It remains to be seen whether the task force will process the whole Gurlitt collection by the end of 2015 as expected. Only then will the museum in Bern know how many pictures are free of suspicion of being stolen and can be sent to Switzerland. It is also unclear what role a Swiss research group will have in the investigation.

Open questions

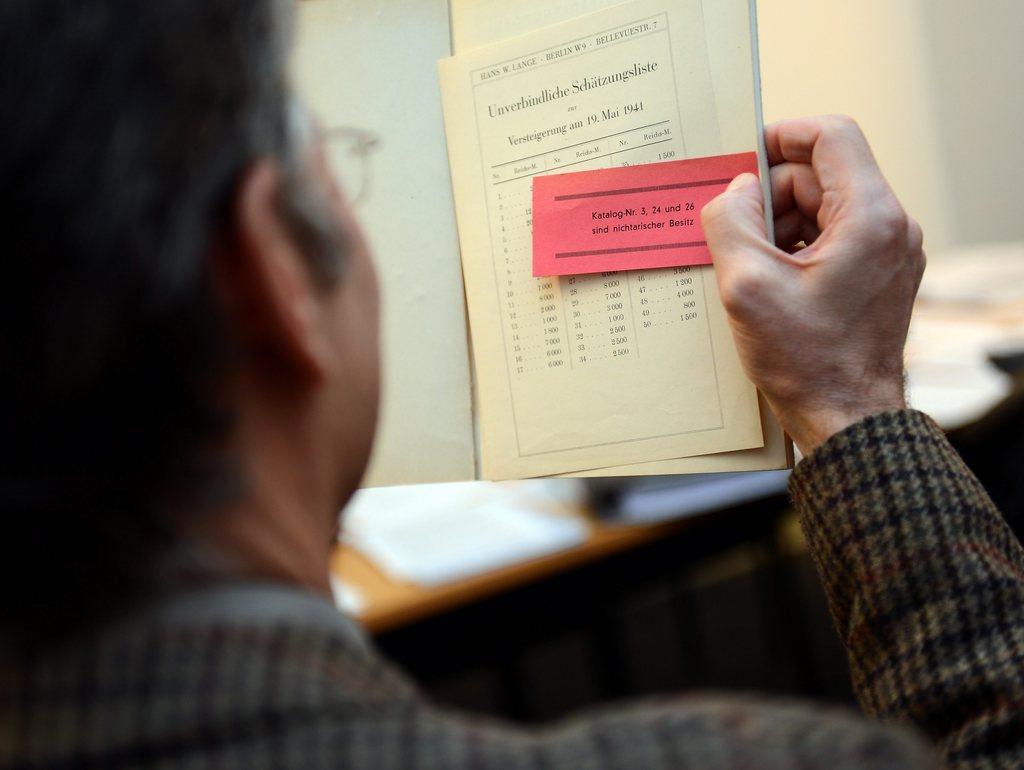

The field known as “provenance research” is a kind of detective work, as professor Gilbert Lupfer, head of provenance research at the State Art Collections in Dresden, explained to swissinfo.ch. The experts – mostly art and regular historians – first check out obvious information like the subject of the painting and the artist’s signature and date. That still says nothing about who has been in possession of the picture. When was the work sold, for what reason, and to whom? Important information can often be found on the back of the canvas.

“There we often find traces – labels or chalk inscriptions that indicate a previous owner, an auction or an exhibition. These are all important evidence,” says Lupfer.

At the same time Lupfer is playing down the expectation that the task force will be able find all cases of potential stolen art and establish their provenance unambiguously. “In my experience,” he cautions, “there are always going to be pictures where you just get no further.” In the case of prints, which are not unique but produced in fixed numbers, it can be especially difficult.

Archival research

If a picture has gone through an auction, the researchers look up the relevant auction catalogue, and also study the archives of the art galleries that sold the works. These galleries, which worked together with dealers like Cornelius Gurlitt’s father, were a major conduit for art in the 1930s and 1940s. So their archives contain important documents that can be used to identify the original owners.

Alarm bells ring with provenance researchers when they find references to German auctions between 1933 and 1945. Many of these were for the sale of Jewish property. A look in old municipal address registers can also provide information as to whether the sale of a work of art was due to anti-Semitic persecution, for example, if the owner gave up his residence just after the sale. And if what was known as a “tax on Jewish fortunes” was paid directly to the revenue authorities following the sale, the case is clear.

Researchers are also interested in the art dealers themselves. A lot of questions remain about Gurlitt’s father Hildebrand, who amassed this controversial collection and bequeathed it to his son Cornelius.

“I would like to see more research done on him,” says Lupfer. “How exactly did he operate?”

Challenge for researchers

In the coming months and years, German provenance research will have an opportunity to prove its new-found maturity. For decades the German art business showed little interest in getting into the quagmire of stolen and looted art and coming to terms with its own failings during the Nazi period. It was only in 1998, when it signed up to the Washington Principles, that Germany committed itself to returning looted and stolen art to the original owners or their heirs.

This put the spotlight on a field of research that had been neglected up until then. One of the pioneers of German provenance research is the State Art Collection in Dresden. With its holdings of 1.5 million works of art, this is the second largest group of museums in Germany. Since 2008 it has been building up a database named “Daphne” to analyse the provenance and history of all the holdings of the Dresden museums.

“A lot has happened in the last few years,” says Lupfer. “Around 2005 there were only a few museums which could carry on provenance research in an intensive and professional manner. In the meantime, even smaller museums have seen that they have to concern themselves with the issue. There has been an increase of awareness.”

Provenance research in Germany

Databases like “Daphne” in Dresden are now one of the main tools for provenance researchers. This is where they look for initial information sources if they are in doubt about a particular work of art.

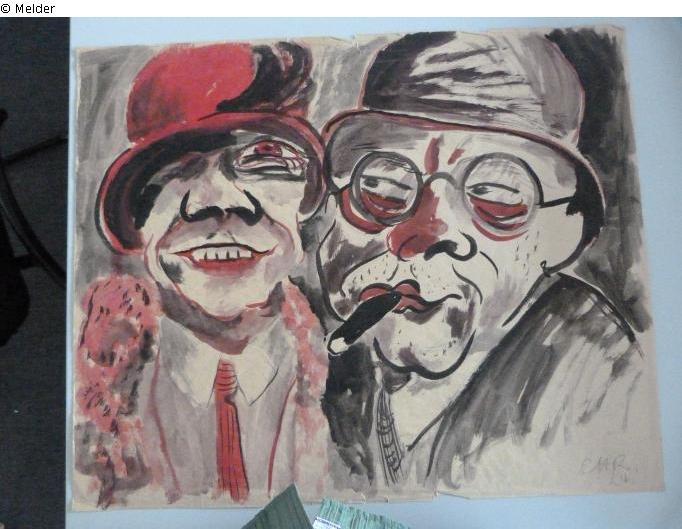

For researchers who concern themselves with “degenerate art” – as the Nazis called the work of the avant-garde artists they persecuted – a similar database of these works is being put together at the Free University of Berlin.

In Magdeburg there is a coordinating office for lost cultural treasures. It administers the “Lostart” database,External link in which internet users can see 29,000 suspected works in public collections. In 2015, also in Magdeburg, the long-planned German Lost Art Foundation is to be established, to carry on provenance research with the support of the federal and local authorities.

Established in 2008 at the Institute of Museum Research of the State Museums, the Centre for Provenance ResearchExternal link in Berlin has, in the space of a few years, become a major facility in the field. It encourages provenance research in 90 locations around Germany, not just in art museums.

(Translated from German by Terence MacNamee)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.