Balenciaga’s legacy: when Spanish art met Swiss silk

Fifty years after his death on March 23, 1972, Cristóbal Balenciaga’s contribution to the history of fashion is stronger than ever. It was in Switzerland that his designs were first elevated to an art form, a status that the brand carries still today.

Cristóbal Balenciaga, the Spanish fashion designer who died 50 years ago, was a contemporary of some of the most influential creators in the fashion business, such as Coco Chanel and Christian Dior. His peers called him “The Master” of couture.

His most important legacy is probably the interaction of fashion and art, and his work is exhibited like art in museums, including the Cristóbal Balenciaga Museoa in Getaria, a Basque village in Spain where he was born in 1895.

The Balenciaga fashion house, founded by the designer in 1917, had a rollercoaster existence. Because of the Spanish Civil War, it moved to Paris in 1937; in 1969 Cristóbal Balenciaga decided to close shop, shortly before his death in 1972. It was reopened in 1986, under a new direction, and today belongs to the luxury group Kering. The brand, which has been under the creative direction of the Georgian Demna Gvasalia since 2015, is still associated with bold designs.

Haute couture enters the museum

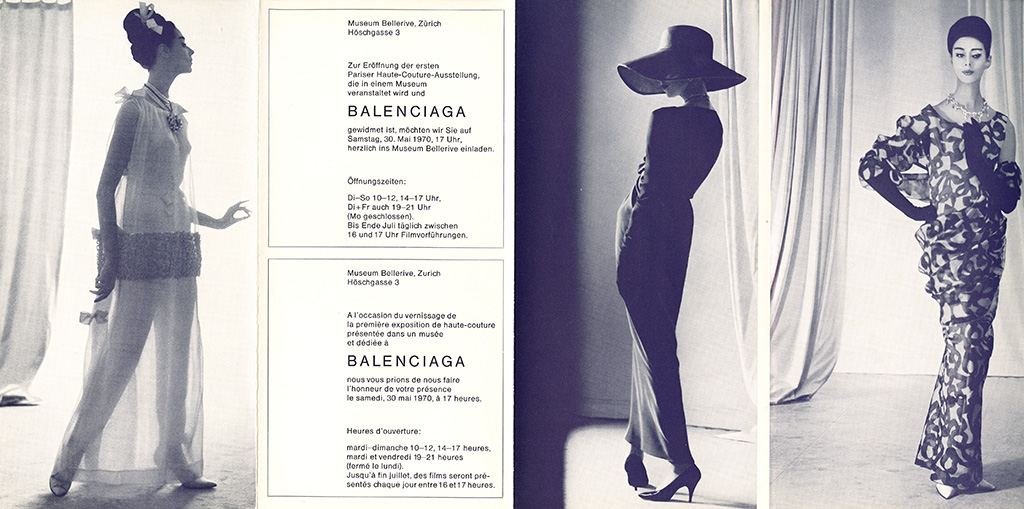

A lesser-known fact about the fashion house is its Swiss connection. It was in Switzerland that haute couture first became art, thanks to a show dedicated to the Spanish fashion designer in 1970 at the Bellerive Museum in Zurich. This was a world first and took place three years before the Metropolitan Museum’s ground-breaking exhibition The World of Balenciaga.

The Bellerive had just opened its doors in November 1968 and was looking for ways to make an impact in the cultural scene. Enter Verena Bischofberger, then director of the fashion design course at the school of applied arts in Zurich.

When news spread that Balenciaga wanted to close his shop and retire, Bischofberger decided to buy a series of garments from the Balenciaga fashion house and start a collection for the school.

She contacted Gustav Zumsteg, who is the owner of the Abraham textile company and an art collector and close friend of the couturier. A meeting was arranged in Zurich in September 1968, followed by a trip to Balenciaga’s headquarters in Paris, where Bischofberger made her selection of garments for the Bellerive exhibition.

In May 1970, the Bellerive Museum opened the show Balenciaga: Ein Meister der Haute Couture (Balenciaga: a master of haute couture), the only art exhibition of his works organised while he was still alive. The retrospective displayed the clothes that the school had bought alongside loans from Balenciaga and two of his clients.

The Zurich show, attended by over 10,000 people, was a milestone in fashion exhibitions, and many of its pieces were later requested by the Metropolitan.

Swiss silk

The textile industry is one of Switzerland’s oldest. In the second half of the 19th century, Zurich was the second largest silk producer in the world, most famous for its black taffeta.

Balenciaga used Swiss silks from the Abraham Company in his designs. Abraham AG (Abraham Ltd) was founded in 1878, and in 1943, Gustav Zumsteg joined as a partner.

Under his command, Abraham AG became a constant presence in the Paris haute couture scene. At its peak in the 1960s, the company supplied fabrics to couturiers like Dior, Givenchy and Ungaro, and above all Yves Saint Laurent and Balenciaga.

In Paris, as well as circulating in the world of haute couture, Zumsteg came into contact with artists such as Matisse, Braque, Chagall and Miró, and acquired a collection of Modernist masters. Some of these artworks still decorate the walls of the famous Kronenhalle restaurant in Zurich that belonged to his mother.

The relationship between Balenciaga and the Swiss firm Abraham AG began in the 1940s, based on the search for a material that would allow Balenciaga to develop increasingly pure and abstract forms.

“Balenciaga expressed his aesthetic ideals to Zumsteg, in which elegance, comfort, exquisiteness and abstraction were essential,” says Igor Uria, Director of Collections at the Balenciaga Museum. In 1957, the Abraham Company created for Balenciaga the gazar: a stiff silk material that the couturier used in his cocktail, evening and wedding dresses.

For the wedding of the future Queen of Belgium, he designed a dress in Abraham’s silk satin. According to Uria, the gazar “allowed him to capture the elegance and abstraction of the female body in a conceptual and aesthetic minimalism.”

The ‘triumph of simplicity’

The trained tailor quietly developed his ideas for almost two decades in the Basque region – away from the spotlights of Paris, but very close to the European bourgeoisie and nobility that spent their holidays in San Sebastián. Spanish royals were among his clients.

In 1937, he opened a shop in Paris, and the first collection he presented in the world’s fashion capital stunned the haute couture industry. His innovative style removed any hint of the superfluous, concentrating on simplicity and purity of line. His designs were also revolutionary in the way they reshaped the features of the female silhouette.

“While Christian Dior captivated with the New Look, Balenciaga opted for fluid lines, curved backs and volumes that defied all the conventions of the time,” Uria told SWI swissinfo.ch.

Balenciaga’s change in the portrayal of the female figure was feted by the specialised press. Carmel Snow, then editor of the American magazine Harper’s Bazaar, wrote in 1953 that Balenciaga represented “the triumph of simplicity”.

From 1937 to 1968 he was the benchmark of haute couture in Paris. He continually renewed proportions and shapes, inspired by classical Spanish paintings and his Basque origins. He sought new fabrics and continuously refined his minimalist silhouettes until by the end of the 1960s he achieved what he called the maximum level of simplification.

In 1962 he presented the one-seam sari dress, an invention that would lead to the creation of his 1967 wedding dress in silk gazar, also with only one seam. Still very modern today, it is considered the most ingenious wedding dress in the history of bridal fashion.

Balenciaga’s training as a tailor shaped his idea of couture, based on the perfection of the cut and the qualities of each fabric. Christian Dior once said that “we do what we can with fabrics. Balenciaga does what he wants”.

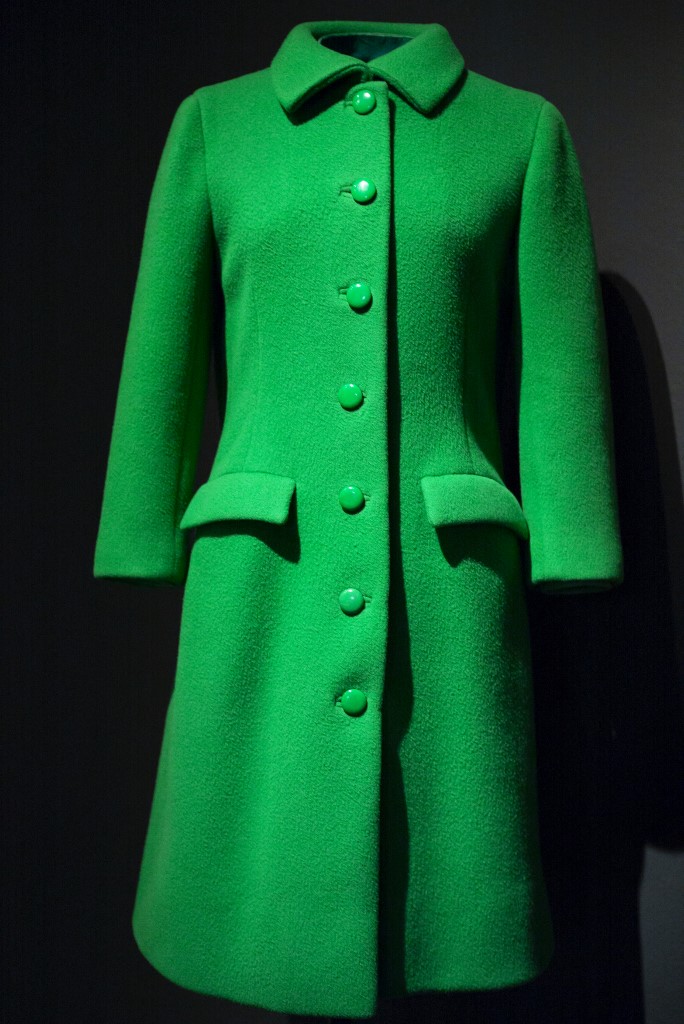

Balenciaga used a varied palette of bright colours, never seen before on the catwalks: yellow, green, fuchsia, violet and orange. He also combined something that seemed impossible before: brown and black. He said black allowed him to focus on the cut, the volumes and the fabrics, which he enriched with embroidery, sequins and beading.

Comfort first

Balenciaga laid the foundation for what was to come. He simplified clothes to the extent that dressing up became part of daily life – so much so that by the mid-1950s many garments could be put on and taken off over the head.

First came the dropped shoulders, then the ruffles. And then, the half-fitted suits, sailor suits, tunics, sack dresses, three-quarter sleeves, ever-smaller jacket collars and dresses without a waist (known as baby-doll dresses). All his contributions promoted comfort and are still fashionable today.

He presented his last collection shortly before May 1968. That same year, he created his only “industrial” work when Air France commissioned him to design the uniforms for its stewardesses. It was a challenge for someone who had never worked with mass production, but also a sign of the new times: the first steps of haute couture into the world of prêt-à-porter.

That was not Balenciaga’s world anymore. In 1968, he announced his retirement.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!