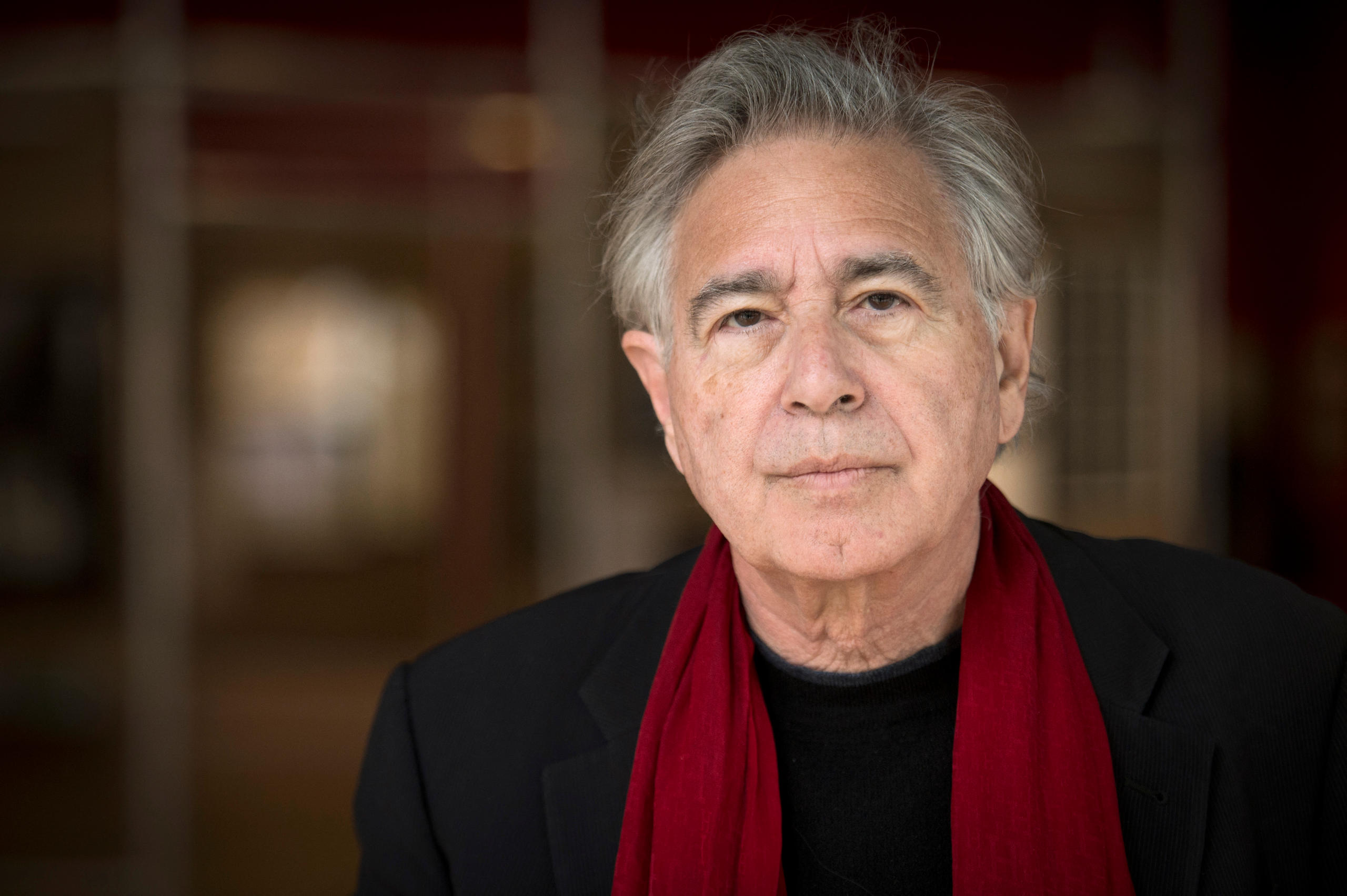

Bernard Tschumi: unbuild to rebuild

From theorist to star architect, Bernard Tschumi was almost 40 years old when he realised his first project. His designs for Paris’s Parc de la VilletteExternal link launched his international career and is considered a masterpiece of deconstructivism.

The Paris Parc de la Villette is dotted with 26 staircase-like forms in fire-engine red. Visitors are treated to half-finished bridges, walk-in structures like cafés or kiosks, and climbing towers for children. They look like creative installations, taken apart and then put back together defying any normal sense of scale or familiarity, arranged in a grid across the site.

The project is the first built work by the Swiss architect Bernhard Tschumi. It came to life in 1983, and the commission for the park came just at the right moment, TschumiExternal link told the Amsterdam-based online magazine FRAME.

The former industrial site in northern Paris finally gave him the opportunity to realise his own idea. His follies – the name for ornamental garden buildings, but also for his architectural flights of fancy – were designed to orientate the visitors, but without guiding them.

There are connections marked out in blue, but the visitor can choose any number of paths – none of them are fixed. Tschumi’s plan convinced the jury, winning out against 470 other teams from 70 countries. In an interview with the London-based online magazine Dezeen, he characterised the whole park as “the largest deconstructed building in the world”External link.

Disassemble and then reassemble

Prior to the Paris commission for Parc de la Villette, Tschumi’s visions had only appeared on paper as drawings. The project made him a household name – launching him beyond the narrow confines of the architectural cognoscenti who knew him from his theoretical writings. Moreover, the project cemented his reputation as a cofounder of deconstructivist architecture, a movement that was making waves in the architectural scene of the day.

It was a protest cry. The 1980s were “the most conservative architectural period in the 20th century”, recalled Tschumi in a 2004 interviewExternal link with the New York-based Curatorial Project, a non-profit promoting the role of architecture in cultural life. Following the sobriety of modernism, architects began rummaging around amongst the building blocks of the past and post-modernism suddenly made columns and ornamentation aesthetically respectable again.

Tschumi and his kindred spirits recoiled in horror, each of them setting out to draw up alternative concepts. In 1988 the New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMAExternal link) dedicated a high-profile exhibition to seven of them: Zaha Hadid, Frank Gehry, Rem Koolhaas, Daniel Libeskind, Peter Eisenman and Coop Himmelb(l)au, as well Bernard Tschumi himself.

The title, Deconstructivist Architecture, became a programme, or for that matter a sort of label for the work of the architects showcased in New York. They shared an interest in philosopher Jacques Derrida’s idea of deconstructivism and they wanted to blow the old apart, or dismantle and reshape it, instead of hiding behind historical forms.

However, Tschumi was never happy with the term.“We wanted to be contemporary. We didn’t want to be another movement, because movements come and go,” he said in the same 2004 interviewExternal link. The purpose was “placing architecture back in the realm of ideas and invention”.

This is what they then did, each in his or her own way. The fundamental idea of fragmentation and combination is the distinguishing feature, for example, in Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim MuseumExternal link in Bilbao, Spain, or Daniel Libeskind’s extension to the Jewish MuseumExternal link in Berlin, Germany.

As a group, they distanced themselves from familiar design idioms. Instead their buildings were sometimes flowingly round, sometimes zigzagged, as if broken and then pieced together again, simultaneously confusing and fascinating the viewers while launching them on strange trajectories inside.

A paper architect

In the eighties, when the MoMA exhibition took place, Tschumi was living primarily in New York. Born in 1944, the United States had always fascinated him. In his interviews he repeatedly describes a decisive moment his life, looking down from Chicago’s highest building as a 17-year-old exchange student and being transfixed.

As Tschumi told the Architectural ReviewExternal link, “visiting Chicago, I suddenly discovered what a city could be”, and it “just changed my view of the world”. It was there he decided to become an architect.

Tschumi was primarily educated in Switzerland. The son of a French mother and a Swiss father, he grew up between Lausanne and Paris. His father was the famous Swiss architect Jean Tschumi, who for instance designed the headquarters of food multinational Nestlé in the town of Vevey on Lake Geneva. Like many renowned Swiss architects, Bernard Tschumi studied at the federal technology institute ETH Zurich.

But at some point, his home country felt too much of a backwater to him. In the 1960s the avant-garde discussions were taking place elsewhere, and Tschumi craved to join them. His first port of call was Paris, then London and then New York, always in search of ways to break down the rigid boundaries between architecture and art. He discussed with intellectuals like Jacques Derrida, lectured, drew, wrote papers. From the eighties on, he commuted between New York and Paris and kept offices in both cities. Tschumi built projectsExternal link in the United States, Europe and Asia.

The structuring element at the heart of his ideas and his work has always been people in motion, the users of his buildings – a leitmotif that was already set out in his Manhattan TranscriptsExternal link. They were developed between 1976 and 1981 in New York, and today enjoy a reputation as classic texts. Tschumi’s drawings for the series have the look of choreographic dance instructions, depicting people moving in spaces. Based on tracing these vectors of directional movements, concepts then emerge.

Architecture provides scope for these movements, without rigidly controlling them. Nevertheless, the key thing about the Manhattan Transcripts, like Tschumi’s other early designs, is that they didn’t have to prove themselves in reality, keep to a budget or compromise with the whims of a client. They exist only as theory, which is why the theorists of the time like Tschumi got stuck with the label ‘paper architects’.

A distinctive non-style

When Tschumi was finally given the opportunity to actually build, his revolution against the mainstream of the eighties didn’t culminate in a signature design language. There is no such thing as typical Tschumi style unlike, for instance, Canadian-American architect Frank Gehry, whose predominantly gleaming metal-covered, twisting sculptural structures became his trademark.

The new Acropolis Museum in AthensExternal link, completed in 2009, counts as one of his internationally most famous buildings. Situated across from the Pantheon, the museum is a real tour de force. It ingratiates itself with the uniqueness of the historical location, echoing the Acropolis without overshadowing it. This is the opposite of the glazed blue apartment block BLUEExternal link, rising up in the midst of the brown-brick buildings of Manhattan’s Lower East Side Manhattan, which attracts maximum attention.

What both buildings nonetheless share is the architect’s philosophy. Always begin with a questionExternal link, he advises. And never think you already know the answer. Above and beyond existing ideas and what is physically realisable, what can architecture actually be? Where do we end up if we leave the feasible and the familiar aside and make room for imagination? These confrontations, this play of possibilities, the links to film, literature and philosophy are all part of the basis of Tschumi’s designs and projects.

Tschumi defines architecture as an interaction between space, happenings and movement. In Parc de la Villette this results in the layout of the creative red structures mentioned above. The same applies to buildings. The concept and the movements are more important than the form; they stand in the foreground. “Concepts differentiate architecture from mere building… a bicycle shed with a concept is architecture; a cathedral without one is just a building,External link” explains Tschumi in remarks quoted by Rethinking The Future – RTF, an online platform focused on architecture.

Successful urban architecture is like a board game, such as Monopoly or chess, according to Tschumi. The architect designs the board and a couple of rules, and then people elaborate it, use it in their own way in a process of endless interaction. Tschumi often works with hanging, open-air walkways that cross at an upper level of the building, also providing space to relax. A good example of this is the Lerner Center at Columbia University in the US, where Tschumi also taught between 1988 and 2003.

For a long time Switzerland obviously found Tschumi’s designs to be not down-to-earth enough. The Swiss German-language newspaper NZZ once lamented the ignorance of his home country with regards to his work. But Switzerland eventually plucked up the courage to commission him. In 2005, he built the headquarters for the Swiss watch manufacturer VacheronExternal link in Geneva, and in 2014 the UFO-like Carnal HallExternal link on the campus of the elite Le Rosey boarding school. The two structures symbolise Tschumi’s triumphant return to Switzerland.

More than Le Corbusier

Our series portrays influential and quirky Swiss architects of the last hundred years. How did they shape the way we think about space? Where in the world have they left their mark? And which buildings still impress us today?

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.