Big Bang machine passes first test

Cheers echoed around the Cern control room near Geneva on Wednesday as scientists celebrated the first test of the world's most powerful particle accelerator.

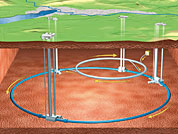

It took less than one hour for the inaugural beam of protons to be successfully guided around the 27-kilometre ring housing the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). Scientists hope to recreate conditions just after the so-called Big Bang, 13.7 billion years ago.

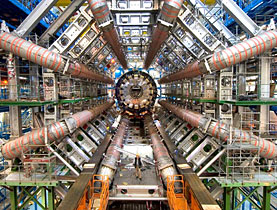

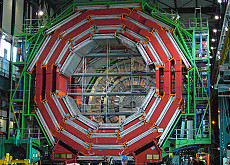

Experts say it is the largest scientific experiment in human history and could unlock many secrets of modern physics and answer questions about the universe and its origins. The LHC is also the biggest and most complex machine ever made.

After a series of trial runs, two white dots flashed on a computer screen at 10.36am local time, indicating that the particle beam the size of a human hair had travelled clockwise the full length of the tightly sealed chamber 100 metres beneath the Swiss-French border.

Scientists from the European Organization for Nuclear Research, known by its French acronym as Cern, later sent another beam around the chamber in the opposite direction.

“My first thought was one of relief,” Lyn Evans, LHC project leader, told journalists after the beam finished its first lap. “It is a machine of enormous complexity and can go wrong at any time, but this morning has been a great start.”

Evans didn’t want to set a date but said he expected scientists could conduct collisions for their experiments “within a few months”.

“Baby”

“The atmosphere here was absolutely electric,” British PhD student Tom Whyntie told swissinfo. “It’s unbelievable to think that we’re finally here and the beam has gone all the way around.”

The collider is designed to push the proton beam close to the speed of light, whizzing 11,000 times a second around the tunnel. If everything goes to plan, two beams will be fired in opposing directions and smashed together in four bus-sized detector chambers, creating showers of new particles that can be analysed by powerful computers.

The Cern laboratory will start stepping up the power with the hope of reaching a new threshold of energy by the end of the year. Further increases are planned until the equipment runs at full power, probably by 2010.

This is just the beginning of a long experiment, physicist Daniel Denegri, told swissinfo.

“The baby has just been born, or I should say twins as there are two beams, but they have to grow up,” he said. “Our main concern now is to increase the number of protons step by step and ensure we don’t damage the machine. But it’s like a new car, you don’t step in it and start driving at 160km/h.”

Black hole fears

Physicists around the world will be watching whether the collisions recreate on a miniature scale the heat and energy of the Big Bang, a theory of the origin of the universe that dominates scientific thinking.

The organisation has repeatedly refuted suggestions by some critics that the experiment could create tiny black holes of intense gravity that could suck in the whole planet.

“It’s nonsense,” said James Gillies, chief spokesman for Cern.

The organisation is backed by leading scientists such as Britain’s Stephen Hawking in dismissing the fears and declaring the experiments to be absolutely safe.

Once the particle-smashing experiment gets to full speed, data measuring the location of particles to a few millionths of a metre, and the passage of time to billionths of a second, will show how the particles come together, fly apart or dissolve.

Higgs boson

It is in these conditions that scientists hope to find fairly quickly a theoretical particle known as the Higgs boson, named after Scottish scientist Peter Higgs who first proposed it in 1964. The particle is sometimes called the “God particle” because it is believed to give mass to all other particles and thus to matter that makes up the universe.

According to Denegri, there is a high chance that Cern will find the elusive particle.

“If we are lucky, it might take a year-and-a-half – or it could be up to five years. If nature chose to create the Higgs boson, we will find it,” he said.

The Cern experiments could also reveal more about dark matter – the invisible mass of energy that is believed to form 96 per cent of the universe – antimatter and possibly hidden dimensions of space and time.

The SFr6billion ($5.95billion) project, first conceived in the early 1980s and organised by the 20 European member nations of Cern, has attracted researchers from 80 nations. Some 1,260 are from the United States, an observer country that contributed $531 million (SFr600 million).

But the high costs and years of hard work are definitely worth it, say the experts.

“Mankind has always been about exploration,” Whyntie said. “With particle physics we are not reaching out but looking in to the fundamental building blocks of matter. We’re exploring as far and tiny as we can go to understand how our universe works. What is beautiful about the LHC experiment is that it’s an attempt to answer some of these fundamental questions that everyone asks themselves”.

swissinfo, Simon Bradley in Geneva

Cern was founded in 1954 by 12 states, including Switzerland, and now has 20 member states.

The LHC tunnel is 27km long and runs between Lake Geneva and the Jura mountain range. When it was excavated, its two ends met up within 1cm.

Cables for the LHC contain 6,300 “superconducting filaments of niobium-titanium” that are 0.006mm thick. In total, they stretch more than 10 times the Earth’s distance to the sun.

The LHC contains the world’s largest fridge. Its temperature is colder than deep space.

The LHC’s two proton beams will use as much energy as a 400-metric ton train travelling at 200 km/h.

The system’s magnet contains more iron than the Eiffel Tower.

Data recorded by the LRC will be enough to fill 100,000 DVDs each year.

Heads of state will attend the LHC’s official inauguration on October 21.

In the LHC, high-energy protons in two counter-rotating beams will be smashed together to search for exotic particles.

The beams contain billions of protons. Travelling just under the speed of light, they are guided by thousands of superconducting magnets.

The beams usually move through two vacuum pipes, but at four points they collide in the hearts of the main experiments, known by their acronyms: ALICE, ATLAS, CMS, and LHCb.

The detectors could see up to 600 million collision events per second, with the experiments scouring the data for signs of extremely rare events such as the creation of the so-called God particle, the yet-to-be-discovered Higgs boson.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.