Documenting the last of Malaysia’s Penan nomads

Swiss photographer Tomas Wüthrich offers insight into the way of life of the Penan, a threatened indigenous group from the Sarawak rainforest in Malaysia.

Whether his pictures show hunting with blowpipes or the progress of deforestation, they tell the story of an everyday existence that is vanishing. “But I am not the new Bruno Manser,” he says.

“Hello Tomas, do you want to come with me to visit the Penan in Borneo?”

“You mean the place where Bruno Manser disappeared?”

“Yes there, exactly.”

That is how the story of a farmer’s son from Canton Fribourg who went to the jungle of Sarawak, a Malaysian territory on the island of Borneo, begins. It was a summer’s day in 2014 when Tomas WüthrichExternal link took the phone call from a journalist friend.

“I didn’t know if it would be dangerous. But I said yes before I had even spoken to my wife about it,” he tells us in his sitting room at home in Liebistorf, a small village between Bern and Fribourg.

The death of a farm

After an apprenticeship as a carpenter and a job working with the disabled, Wüthrich stumbled into photography “almost by chance”. When his parents decided to sell the family business in Kerzers, he picked up his camera to tell the story of the last days of this rural life that had been his childhood. “The farmer’s life fascinated me,” he says. “I wanted to document the death of a farm.”

After completing his training as a press photographer at the Swiss Journalism School MAZ in Lucerne, he worked as a photo journalist for the Berner Zeitung and since 2007, he has been freelance. His work for Swiss newspapers and international magazines, which commission him for reportage and portraits, allows him to make a living. “But it’s not always a rewarding job,” says Wüthrich, who is 47. “I always wanted to do something of my own.”

Meeting the Penan

In November 2014, Wüthrich visited Sarawak for the first time. He accompanied a Swiss emergency doctor who travelled from village to villageExternal link for three months to provide healthcare to the Penan people.

The Penan, who number around 10,000, are traditionally a nomadic group who live in the rainforest. They were originally hunters and gatherers but today they mostly live settled in villages, although they still rely on the forest to survive.

Wüthrich remembers well the powerful first impression the lives of the indigenous people made on him. “It was discouraging to see how static the lives of the Penan had become in huts in the bright sunshine, away from their roots.”

The photographer was fascinated to meet a group of Penan who had lived in the jungle until the previous year. “They showed us the trees from which they obtained poison for their arrows, how to make blowpipes, and how to hunt. It was fantastic.”

He travelled to Borneo again in 2015 with one clear goal: to document the daily lives of the Penan still leading a nomadic or semi-nomadic existence in the jungle.

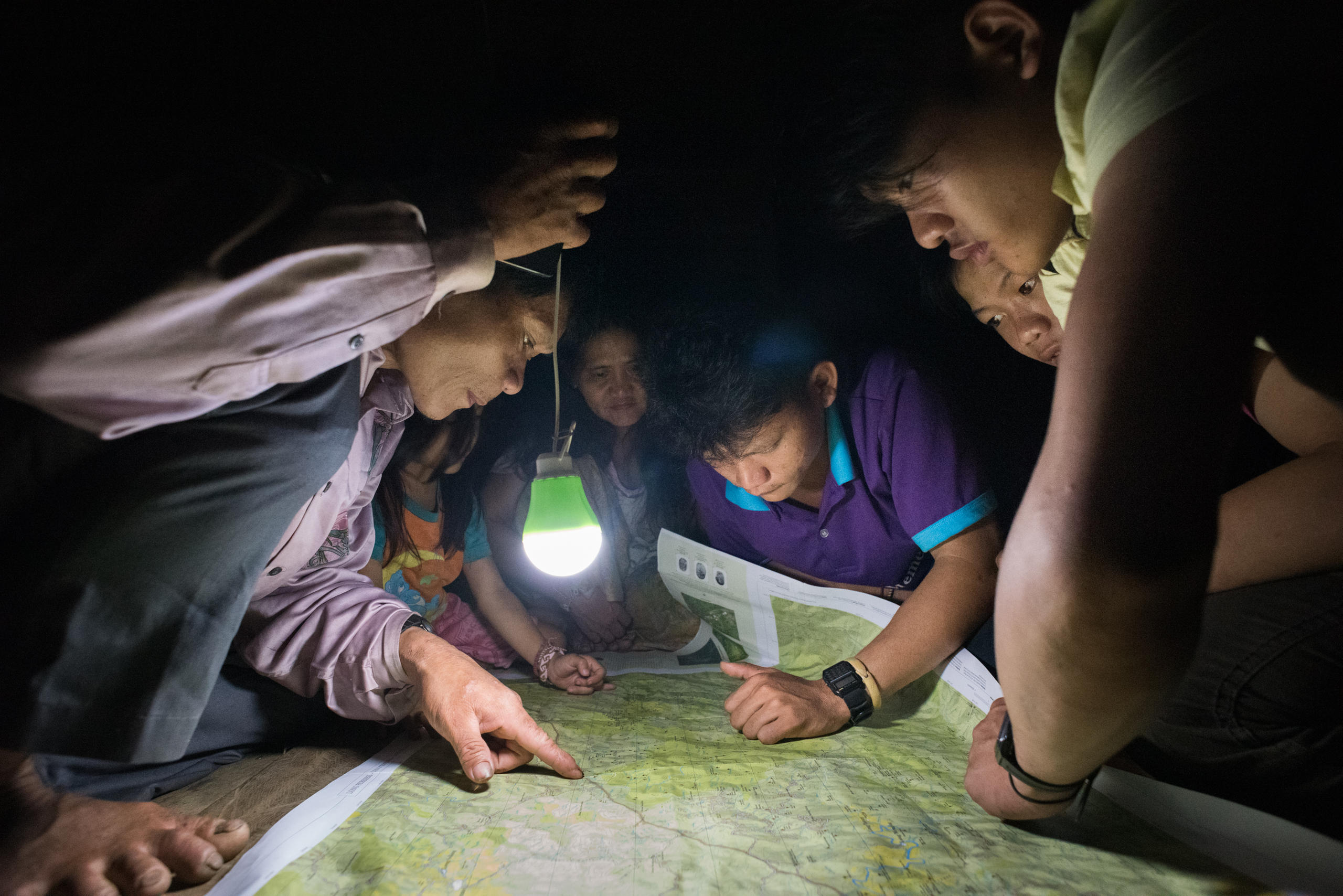

He immediately noticed the “incredible charisma” of Peng Megut, a village tribal chief. This man, who grew up in the jungle, is aware of progress and values some aspects of modern life. However, he remains connected to the old way of life of the Penan. “In spirit, he is still a nomad,” Wüthrich says in wonder.

20 centimes for a tonne of wood

Between 2014 and 2019, Wüthrich spent about six months with the Penan. He has learned the language and values their hospitality. “They are a reserved people, but extremely warm and hospitable, without prejudice,” he says. “I was impressed by the deep culture of sharing.”

Among his most treasured memories is finding himself back in untouched jungle after days of walking. “We built a hut and gathered around the fire to eat sago and meat, surrounded by the chirping cicadas and the sounds of other forest creatures. These were unforgettable moments.”

On his travels, the photographer noticed another aspect – the destruction of the jungle. In many areas, trees are being chopped down for timber by the authorities and private companies. Penan who need money also sell timber. “Sometimes as cheaply as 20 centimes for a tonne of wood,” Wüthrich says with sadness.

The endless palm-oil plantations, cultivated where there was once rainforest, are among the “saddest” aspects of life in Sarawak, the photographer says. “It is shocking to see the speed at which a bulldozer operates. It can dig a path through the forest in just a few minutes.”

The battle between the indigenous jungle people and the logging companies is an unequal one. But the hunters with blowpipes achieved one success: in 2018, when the lumberjacks appeared with a police escort at the barricade erected by the Penan, the engines of the bulldozers were turned off.

Without the permission of Peng Megut, who has accurate maps produced with Swiss supportExternal link, no timber could be extracted here, the police said. “The lumberjacks went away empty-handed,” Wüthrich says.

The mysterious disappearance of Bruno Manser

The Fribourg photographer’s commitment to the region recalls that of another Swiss man; Bruno Manser of Basel. Manser lived on the island of Borneo from 1984 to 1990 and studied and documented the language, customs and traditions of the Penan. He gave many lectures in Switzerland about saving the tropical forest in Sarawak.

Manser disappeared in the year 2000 after he returned illegally to the island of Borneo. He was officially declared dead by a Basel court in 2005. The court said it was clear that “the Malaysian government and the multi-national logging companies had a major interest in silencing Bruno Manser”.

The Bruno Manser Fund (BMF)External link continues his work in environmental protection. The organisation fights for the protection of the tropical forest and defends the rights of indigenous people threatened by deforestation.

Despite their common interests, Wüthrich doesn’t see himself as the new Bruno Manser. “I am not trying to flee our society and I don’t want to hide away in the forest as Manser did,” he says. “My family and my life are in Switzerland.”

Wüthrich praises the amazing work of the BMF, particularly their forest mappingExternal link project, and finds it regrettable that Manser is sometimes wrongly portrayed. The activist didn’t stand at the barricades, as he is shown doing in a new film about himExternal link to be premiered at the Zurich Film FestivalExternal link on September 26.

“Manser’s achievement was that he managed to unite the different Penan tribes and organise a joint resistance,” Wüthrich says. “But he consciously stayed in the background.”

Paradise Lost

For Wüthrich, his experience with the Penan is more than a memory. A selection of the photographs that he took in the jungle and the villages are published in a book, “Doomed ParadiseExternal link,” that he presented in early September at an exhibition of his photographsExternal link at the Kornhausforum in Bern.

“Peng Megut became a friend to me,” Wüthrich says. “He asked me to tell the world about the lives of the Penan. I wanted to do that without giving a romanticised image of life in the jungle. I wanted to show the influence of modernity, too.”

The photographer is under no illusions. The forest and lifestyle in close contact with nature are under pressure and his photos won’t change the world. “But I want to show people that everything is connected: Our use of palm oil has consequences for the Penan, and logging has consequences for the climate.”

Like the nomadic people of Borneo, Wüthrich has changed too. He says he has less fear of the future after his experiences in the jungle. “I live more peacefully,” he says. “I share what I have. And I have opened my house to strangers and taken in an asylum-seeker.”

The Penan tribe

The Penan are one of 24 tribes in Sarawak, Malaysia’s biggest state, located on the island of Borneo. Around 50 years ago an estimated 100,000 Penan were nomadic or semi-nomadic, hunting and gathering food in the forest. Now only around 200 people still live this way.

Logging is seen as the biggest threat to the Penan way of life. It also leads to contaminated drinking water and soil erosion.

Less than 10% of Sarawak’s original primeval forests are intact, according to the Bruno Manser Fund. The Penan and other indigenous groups are still waiting for the recognition of their rights to the land in the forest areas that they have traditionally inhabited.

Translated from German

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.