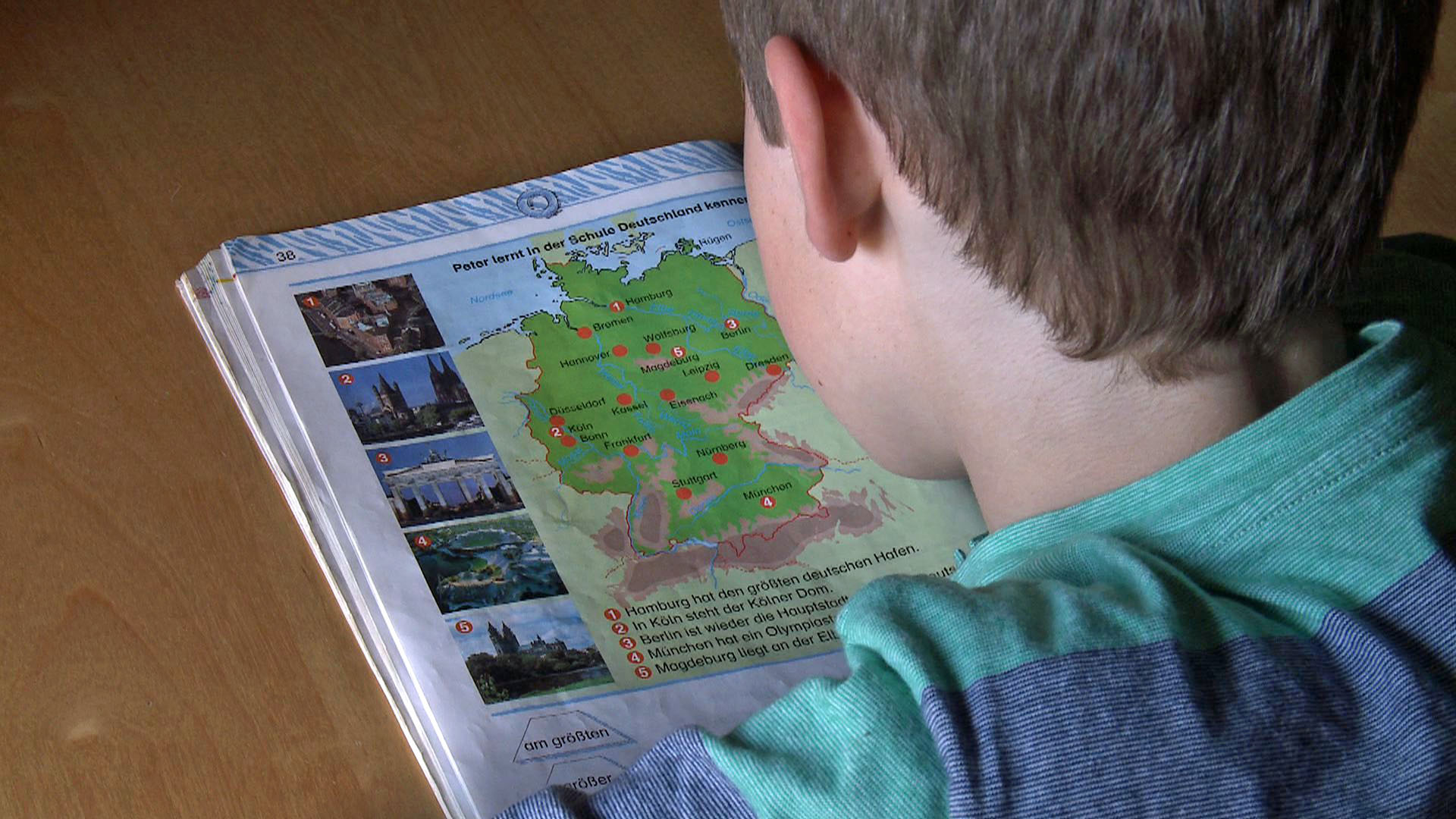

Children take two extra languages in their stride

Supporters of the initiatives for only one non-native language to be taught in Swiss primary schools say two are too much for youngsters to handle. Some educational researchers are much more optimistic about children’s learning abilities.

In a growing number of German-speaking cantons there are increasing calls to teach only one and to postpone the other until secondary level.

The demand for only one other language comes from teachers, who allege the burden on pupils is too heavy. It is also getting political traction through votes in cantonal parliaments or people’s initiatives. This may be surprising, given that brain research has come out very much in favour of early language learning.

More

Why children under 12 learn faster

A matter of good teaching

However, to claim that “the earlier you start, the better the results” would be too simplistic, says Lars SchmelterExternal link, a professor of foreign language teaching at the University of Wuppertal in Germany.

“Successful learning of a foreign language in primary school depends a great deal on teaching being pitched at the cognitive skills of the pupils and the resources available,” he says.

“It is vital that teaching be done appropriate to the age involved,” agrees Andrea Haenni HotiExternal link, another educationalist at a teacher training college in Lucerne.

The researchers add that children also learn how to learn languages. This leads to the development of what they call metacognitive skills: the ability to reflect on one’s own learning, find the best strategies and then decide when and how to use them. This effect is longlasting, on into the teens and adulthood.

Advantage of bilingualism

For the study of early learning of languages coauthored by Andrea Haenni Hoti, researchers compared 30 primary classes in cantons Obwalden, Zug and Schwyz, in which English was taught beginning in the third year (age nine) and French in the fifth year, with 20 classes in canton Lucerne, where at the time only French was taught in primary school.

“We found that bilingual children who may speak Albanian, Turkish or Portuguese at home are more motivated to learn French than monolingual children,” Haenni says.

“Already existing knowledge of a different mother tongue aids learning foreign languages. However, their prior knowledge needs to be recognised in teaching foreign languages and used as a resource.”

Abolish the problem?

In a study for the Swiss National Science Foundation in four cantons of central Switzerland, Haenni found that most primary school pupils had reached the learning objectives set and that they got along fine with two extra languages.

“Of course there are pupils who feel overburdened, just like there are others who don’t feel they are getting enough of a challenge, as happens with all subjects,” she explains.

“But that does not mean that all primary pupils should stop learning a second non-native language or that it should be made optional. In mathematics, for example, there are pupils who do not reach the learning targets, but no one suggests that maths should be abolished or made optional.”

If teaching a second non-native language were to be postponed until secondary school, pupils “would have only three years to learn French, which is a national language. Even if we were able to increase the number of teaching hours, one might wonder if this time is sufficient to acquire the language skills being aimed at,” says Haenni, emphasising that school-leavers who do not have the expected French skills will find themselves at a disadvantage in many work areas.

French before English

On the basis of studies in other European countries – and particularly on the teaching of languages in Luxembourg – Schmelter thinks learning two non-native languages in primary school “is quite doable, without any risk of overload” for most children. However, he wants the languages to be learnt in a particular order.

More

Should schools teach all mother tongues?

“This is because English is morphologically much simpler – there are fewer conjugations. This makes learning English easier in the early years. If they then start French afterwards, they get the feeling they are not making progress, they don’t reach as high a level as in English,” he says.

“If they do it the other way around, they don’t get that feeling. Also, someone who learns French first and then English is more likely to learn a third optional foreign language than someone who learns English and then French.”

Language wars

These findings seem to bolster the case of French and bilingual cantons which object to the fact that French is no longer the first non-native language taught in all German-speaking cantons.

But those who have given precedence to English show no sign of reversing their position. Opponents of the abolition of the second non-native language at primary level are mounting a counterattack in parliament.

The Swiss government has indicated that it will intervene if cantons adopt arrangements “likely to put the second national language at a disadvantage”, for example teaching only English at primary level and thus “putting at risk national cohesion and the needed mutual comprehension among the language communities of this country”.

The “language wars” in Switzerland, as some media now call them, may be only just beginning.

National languages under fire

In canton Graubünden, Switzerland’s only trilingual canton, a people’s initiative is calling for English to be taught as a non-native language – and for no other languages to be taught – in German-speaking primary schools. That would mean a setback for Italian and Romansh, the canton’s two other languages. The initiative will be put to a vote in 2015.

French is the language at stake in other cantons where there have been calls for only one extra language in primary school. In canton Lucerne, the collection of signatures for an initiative is nearing completion, while another initiative was launched in Nidwalden last May. Similar steps may be coming in other cantons where this view has been advocated by local parliamentarians. Before making a decision on the matter, cantonal governments would like to have an evaluation of the teaching of two non-native languages at primary level, expected by 2015.

In only three out of 17 German-speaking cantons (Basel City, Basel Country and Solothurn) is French now taught before English. In all French-speaking cantons, on the other hand, German remains the first non-native language. In the bilingual (French-German) cantons, English is taught as a second non-native language. In Italian-speaking Ticino, three extra languages are compulsory: first French, then German, then English.

(Translated from Italian by Terence MacNamee)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.