Basel faces pressure to return art once owned by Jewish historian

Nine years ago, Basel rejected a claim for more than 100 artworks – including pieces by Edvard Munch, Henri Matisse and Marc Chagall – that had once belonged to the renowned Jewish museum director and art critic Curt Glaser and were purchased by the city’s Kunstmuseum (Museum of Fine Arts). Basel today faces mounting pressure to rethink its decision, both from within Switzerland and abroad.

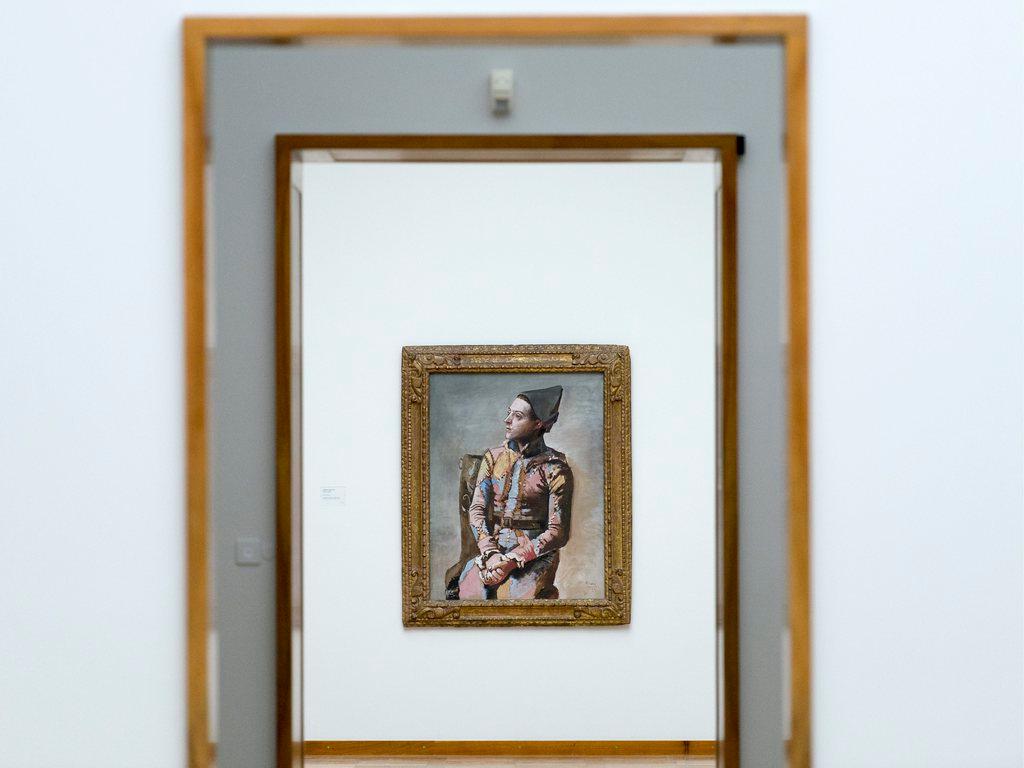

A lithograph of a nude in black, red and blue by Edvard Munch with the title “Madonna,” a watercolour showing two laughing blond girls by Max Pechstein, and a Chagall etching of a musician playing the cello are among the treasures in Basel’s Fine Arts MuseumExternal link. They once belonged to the Jewish art historian and critic Curt Glaser who was the director of Berlin’s Art Library and counted Munch and Max Beckmann among his friends.

But months after the Nazis came to power in 1933, they introduced a law designed to rid the civil service of Jews and political opponents. Glaser was ousted from his post and his apartment. The Gestapo established its headquarters in the building that housed his residence. “He lost everything,” says Valerie Sattler, Glaser’s great-niece and one of his heirs. “He lost his apartment, he lost his job and he lost his employment opportunities.”

He sold his art collection, home furnishings and personal library in two auctions in Berlin and fled the country, finally settling in New York.

Christie’s auction

Museums in Hanover, Berlin, Cologne, Nuremberg, Munich and Amsterdam have restituted items or reached settlements with Glaser’s heirs in recent years, accepting that he sold the art under duress to finance his escape from Nazi Germany.

Two private individuals have also agreed settlements – on December 7, Christie’s will sell a painting by the Mannerist artist Bartholomäus Spranger in London. The proceeds are to be shared between Glaser’s heirs and the private north German collector who hung it over his bed without knowing its history.

Yet Basel has so far stood by its 2008 decision to reject the claim. Back then, the city argued that the museum paid market prices at the 1933 auction and had no way of knowing the art belonged to Glaser. But since 2008, information has surfaced that shows both these arguments to be false.

The minutes of a meeting of the Basel Art Commission from June 1933, discovered in 2010, refer to a curator’s report on the “Glaser auction in Berlin.” The commission, the curator told the meeting, was able “to buy a large number of modern works at cheap prices.”

This new information, revealed recently in a report by the public SRF television channel, has prompted a shift of position in Basel. “We will study the documents to acquire an overview and discuss how to proceed with the museum and the art commission,” said Melanie Imhof, a spokeswoman for the canton Basel City government. “At the moment, everything is still open.”

Felix Uhlmann, the president of the Basel Art Commission, said the panel plans to “examine again the question of the purchase of drawings belonging to Curt Glaser very carefully in the coming months”. Though he conceded that the prices were low, “these were in line with the market during the world economic crisis. That doesn’t mean that we do not recognise the difficult position in which Curt Glaser found himself”.

Gurlitt inheritance

This shift is also a sign of how Swiss attitudes towards Jewish claims for art looted or sold in the Nazi era are changing in the wake of the Bern Fine Arts Museum’s decision to accept Cornelius Gurlitt’s inheritance. The reclusive art hoarder left the museum more than 1,500 artworks, some of them known to have been looted by the Nazis and some of them sold by Jews desperate to leave Germany.

The Bern museum hesitated before accepting the bequest because of the responsibility it entailed.

Marcel Brülhart, vice president of the foundation that runs the Bern museum, told SRF that in his view, Basel’s decision of 2008 “is no longer justifiable from today’s perspective.”

“The Gurlitt case has brought some movement into the discussion,” says Thomas Buomberger, a Swiss historian who has written two books about Nazi-looted art. When the Bern Fine Arts Museum signed a contract with the German government, it agreed to apply the same criteria as Germany in determining what art should be returned from the Gurlitt collection, Buomberger points out.

The German government refers to “art lost due to Nazi persecution,” which encompasses sales under duress.

“This term is broader than the criteria that have until now been applied,” Buomberger says. “There will be discussion about this in Switzerland in the years to come.”

Gradual shift

Swiss museums have in the past rejected claims from Jewish heirs for art that was sold in forced sales or under duress.

Yet Switzerland endorsed the non-binding international Washington Principles on Nazi-looted art. In 2009, these were updated by the Terezin Declaration – also endorsed by Switzerland – which specifically urged that “every effort be made to rectify the consequences of wrongful property seizures, such as confiscations, forced sales and sales under duress of property.”

Glaser’s great-niece Sattler, a cellist in the Nuremberg Symphony Orchestra, also sees a gradual shift in how institutions view her family’s claim – and in how Glaser himself is remembered.

A commemorative plaque to Glaser was unveiled last year at the State Art Library in Berlin, more than 80 years after he fled the city. Hermann Parzinger, president of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, described him as “one of the first victims of the Nazi purges” in an essay.

“It must not be that a man who contributed so much to the museums is only honoured in specialised publications,” Parzinger wrote. “It would be tantamount to a triumph for the Nazis in their attempt to annihilate people and ideas.”

Sattler is cautiously optimistic about Basel’s review. “Very slowly things are changing,” she says. “So, who knows what will happen?”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.