How René Gardi shaped Swiss views of Africa

In “African Mirror”, director Mischa Hedinger recounts the career of photographer and film-maker René Gardi in colonial Cameroon in the 1950s. The documentary suggests that Gardi’s paternalistic, even racist approach says more about his native Switzerland at the time than about the Africa he thought he saw.

“I have always tried not to present a biased vision of reality in my pictures.” René Gardi never doubted the documentary value of his own work, as the Bern film-maker explained in a letterExternal link to an African studies institute in California in 1985, near the end of his life.

This belief system is deconstructed by Mischa Hedinger, himself a young film-maker from Bern, in his documentary African MirrorExternal link, which is now showing in German-speaking parts Switzerland and will be seen in French-speaking Switzerland next Spring.

Why bring a forgotten film-maker out of the shadows? “When the baby-boomer generation think of Africa, the films of René Gardi start to appear”, writes a journalist in the Bern daily newspaper Der BundExternal link in an article on “African Mirror”. Gardi’s reputation, however, was pretty much confined to German-speaking Switzerland, where he was a well-known public figure thanks to his books, lectures and appearances in the media. He did reach a wider audience with “Mandara”, a film made in Cameroon which won a special commendation at the 10th Berlin international film festival in 1960 in the category “best documentary film aimed at young viewers.”

Sex and the colonies

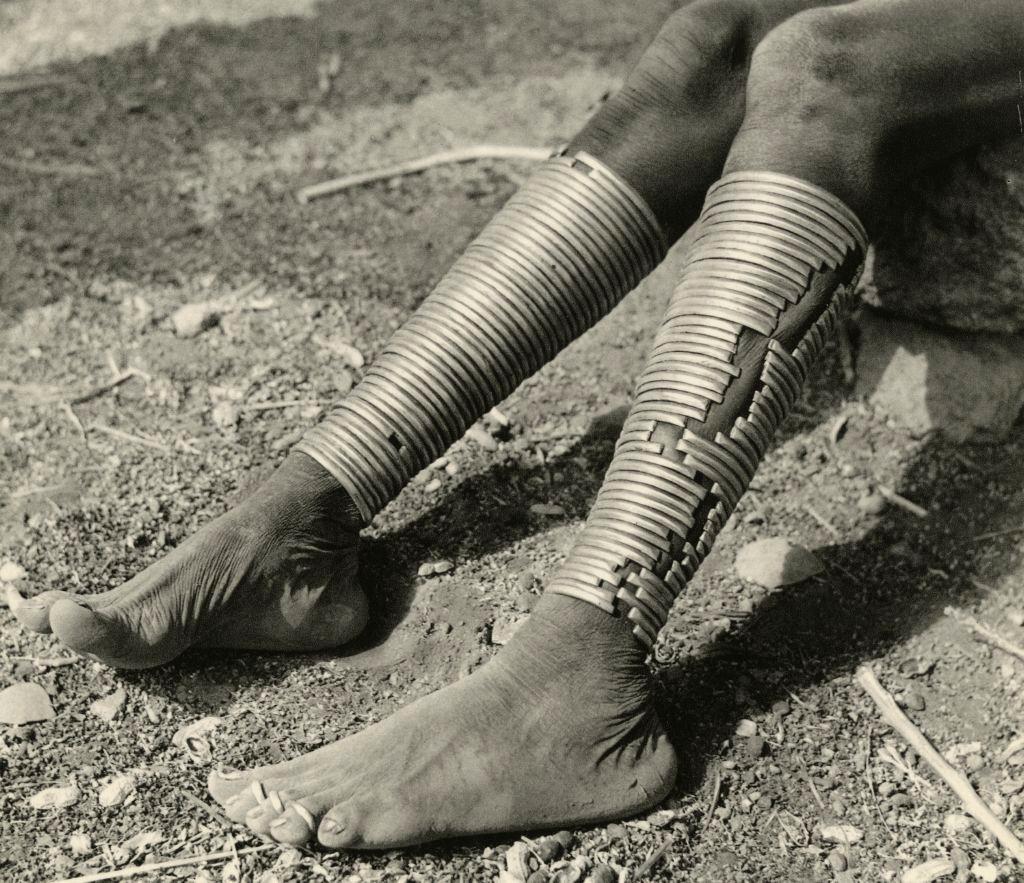

Regarding young people, it could be said that Gardi “appreciated” them in his own particular way. In 1944 he was convicted of sexual abuse of some of his pupils when he was working as a teacher in Switzerland. His paedophilia has not been spoken about until now, but Mischa Hedinger has made it a part of his documentary, linking it to the nude shots of young Cameroonians filmed by Gardi.

“African Mirror” is not really an attack on Gardi, but it does question the representations of Africa that Gardi had a hand in forming. Predatory sexuality is often a key element of the colonial imagination, Mischa Hedinger told swissinfo.ch. He mentions “Sexe, race et colonies”, a monumental study that appeared last year in Paris to considerable publicity. This dark side of this colonial heritage lives on in the form of sex tourism, which continues to be a lucrative business.

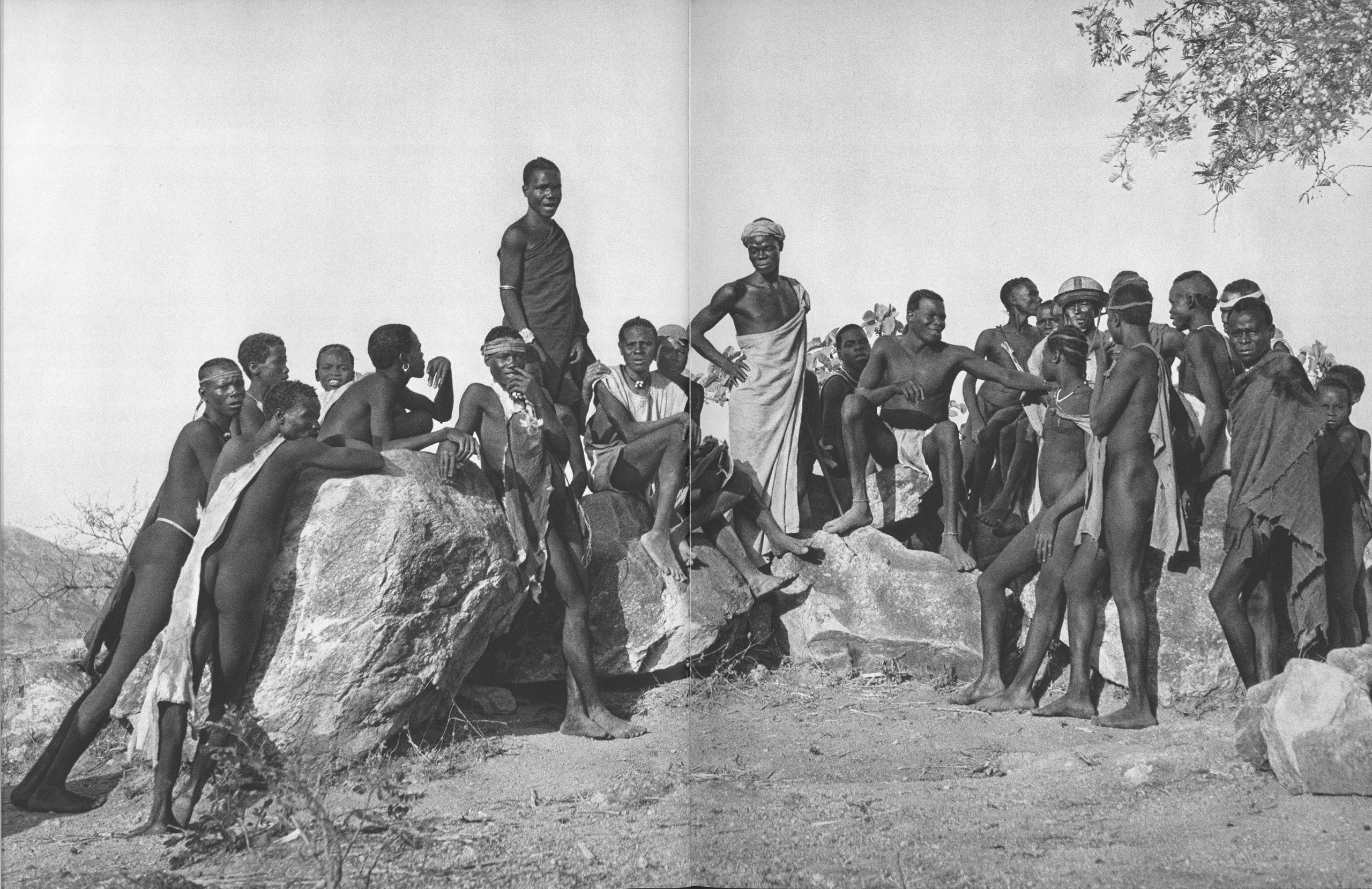

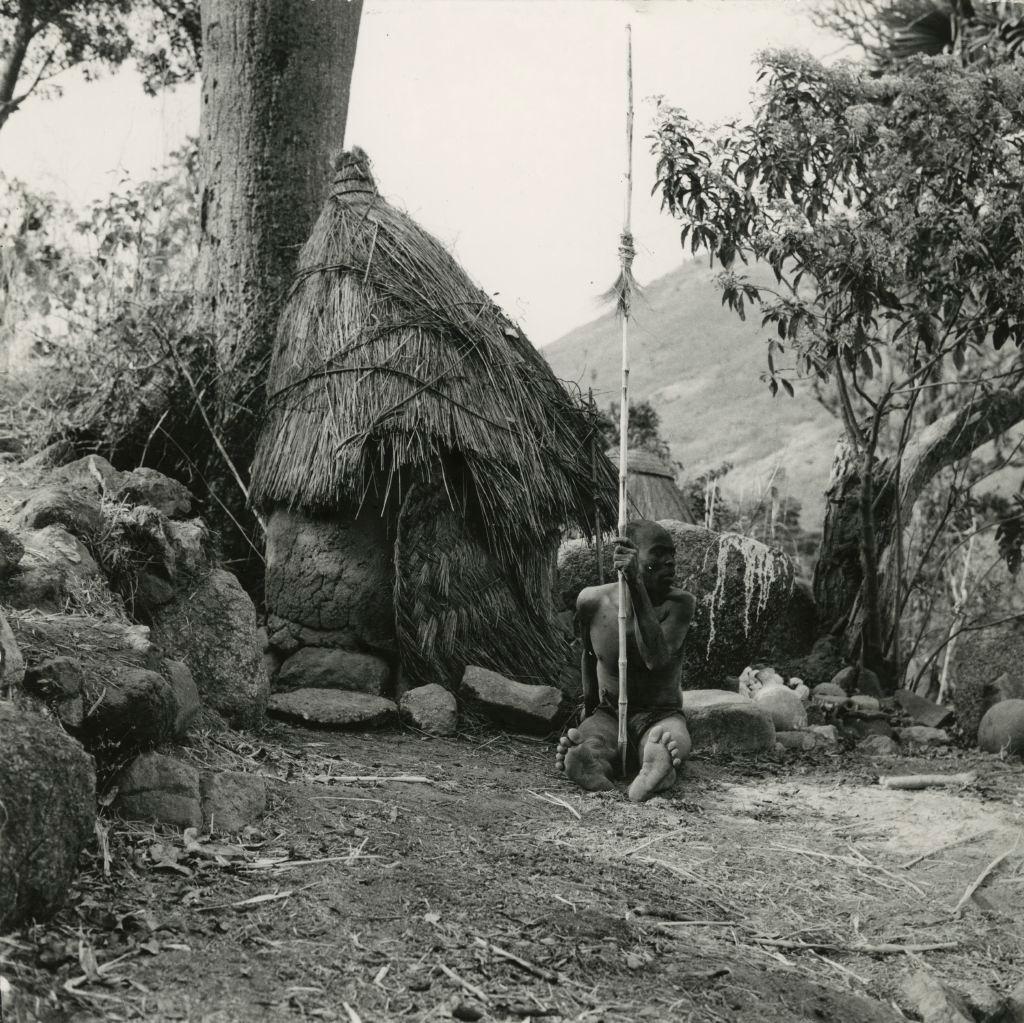

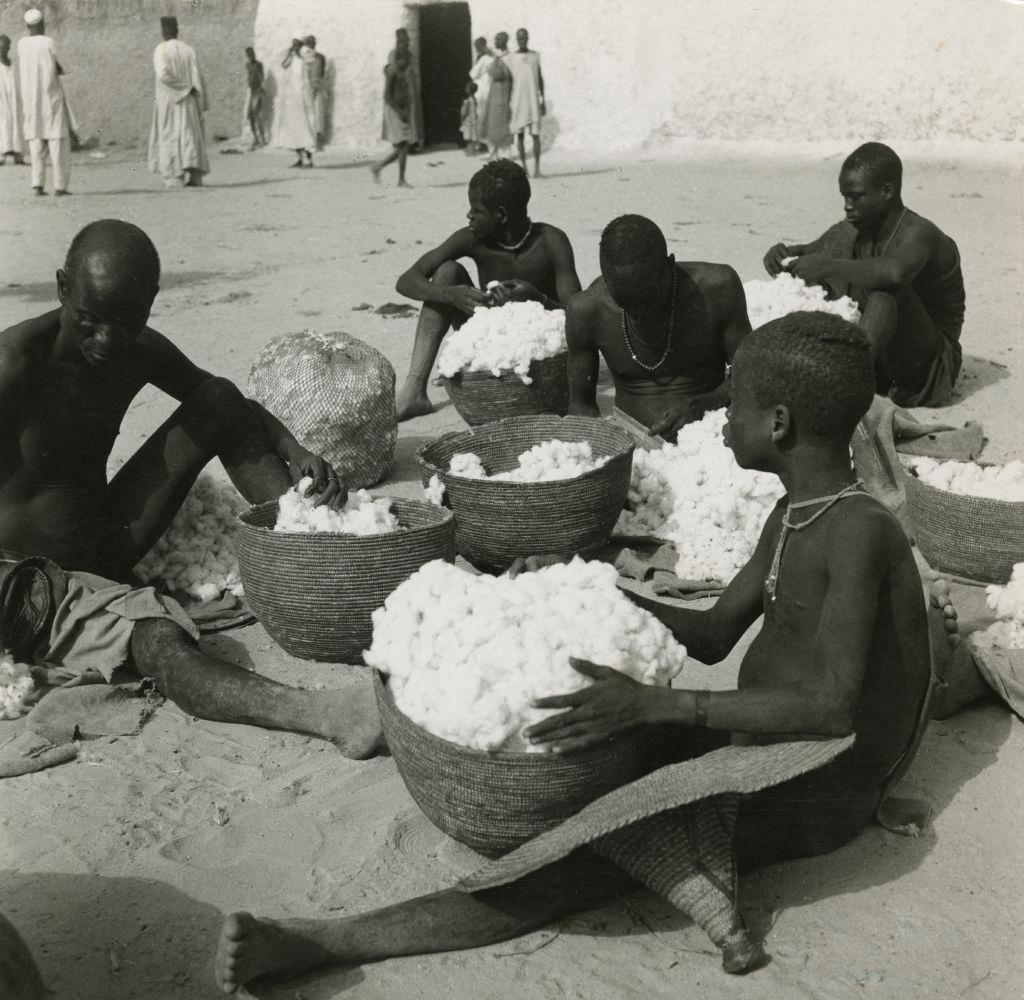

Gardi developed a vision of African peoples in his work. “When I look at the photos I took in years gone by, it often makes me feel very sad. These splendid craftsmen with all their difficulties, their needs, their joys and their stubbornness, people who are artists and artisans all in one without realising it, and all those wonderful mothers in the tents and the villages, who accept their fate with so much calmness and courage, will soon live only in the memory of those who knew them”, he wrote in a retrospective letter.

Noble savage

This myth of the noble savage unaware of his own powers was widely shared in mid-twentieth century, and has not entirely died out, notably in the controversial 2007 speech in Dakar by French President Nicolas Sarkozy, who said that “Africa’s problem is that it is living out its present in nostalgia for the lost paradise of childhood.” This resulted in a storm of criticism from people like the Cameroon writer Achille MbembeExternal link.

But Gardi also drew parallels between the tribes he saw in Cameroon and Alpine dwellers at home. He even went so far as to say: “Sometimes I wish that we Swiss had a colony.”

This is significant, according to Hedinger: “Gardi is expressing little Switzerland’s desire for greatness. The image he forged of Africa was itself a kind of Swiss colony: an imaginary country belonging to the Swiss.”

While Switzerland never had a colonial empireExternal link (although the idea was floated among the elites in the late 19th century), the Swiss government’s overseas development and cooperation agency was not immune to Gardi’s view, notably in Rwanda, the “Switzerland of Africa”. There Swiss development workers were involved up to the highest levels in government, before the 1994 genocide put an end to all that.

(Translated from French: Terence MacNamee)

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.