Documentary shows the concrete reality of Le Corbusier’s Indian utopia

A new film about Chandigarh, the Indian city planned by star architect Le Corbusier, raises questions about cultural imperialism and the requisite “Swissness” of Swiss documentaries.

As is the case for so many events in modern Indian history, the story of the city of Chandigarh begins in 1947. The end of British rule prompted the partition of the subcontinent into majority-Hindu India and majority-Muslim Pakistan. The former province of Punjab found itself straddling one of the newly drawn borders, with its capital city Lahore ending up on the Pakistani side.

Left without an administrative centre, Indian Punjab was quickly deemed by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to be the site where a grand architectural project would showcase liberated India’s economic and cultural ambitions. Instead of a new state capital being designated, one would be built from scratch.

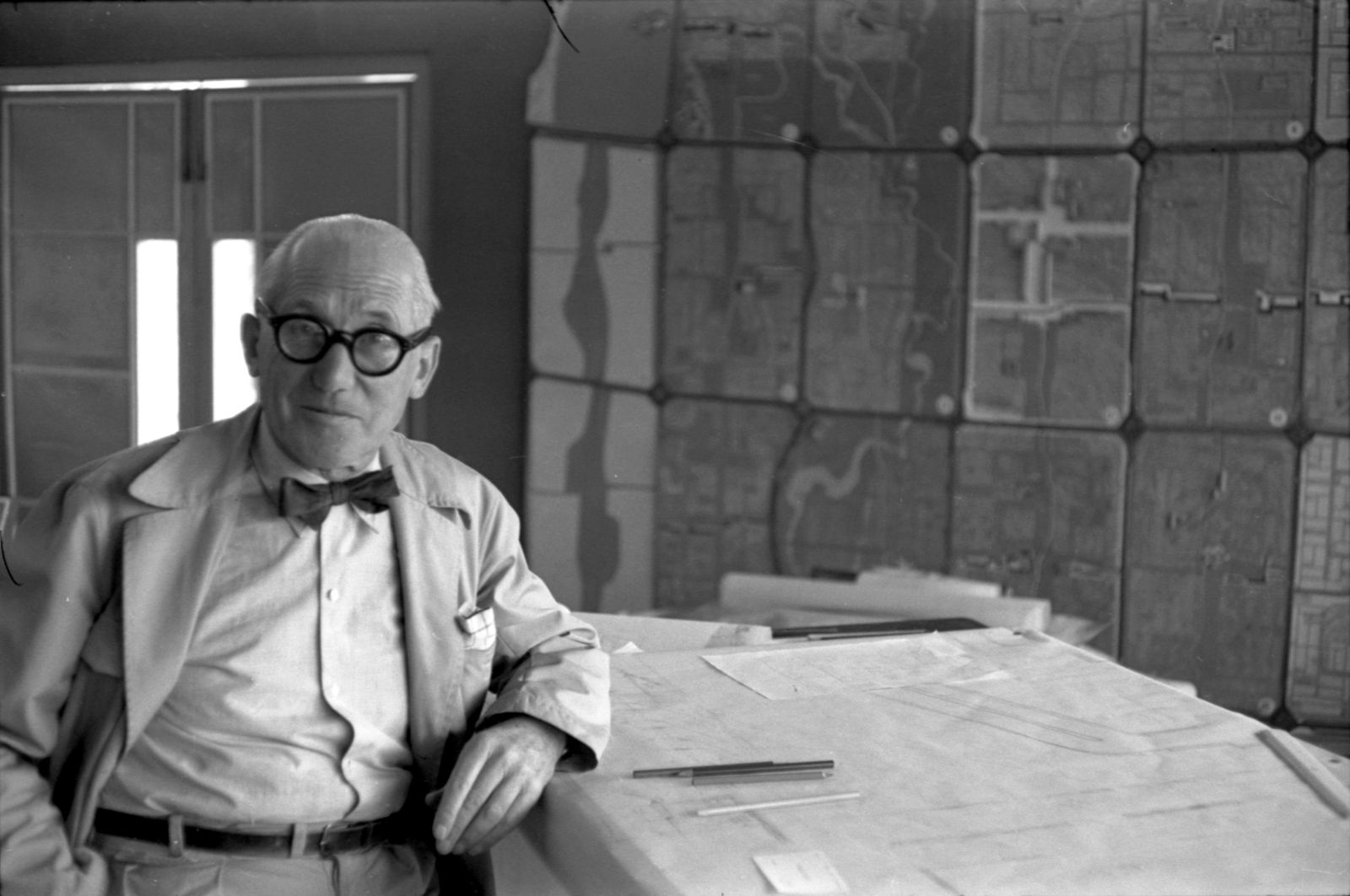

The city was to signify, in Nehru’s words, an India “unfettered by tradition”. The man to design this urban marvel would be Swiss-French celebrity architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, better known as Le Corbusier, a synonym for the trailblazing and divisive radicalism of modern architecture.

A little-known achievement

Today, Chandigarh, which was designed to accommodate a population of 500,000, is a city of about 1 million inhabitants. It serves as the shared capital of the states of Punjab and Haryana, and boasts a GDP per capita that ranks among the highest in India. Architecturally, the city still broadly follows the building codes laid down by Le Corbusier. Its most celebrated collection of edifices, the administrative buildings that make up the Capital Complex, enjoys the status of a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Yet for all the history that swirls around Chandigarh – and in spite of its more prosaic significance as a monument to the collaboration between India and an internationally renowned Swiss-born creative – the city is not exactly a household name in Le Corbusier’s country of origin.

Indeed, it was only by coincidence that Swiss scenographer and filmmaker Karin Bucher became aware of the unlikely connection.

When I ask her and her long-time creative partner and film maker Thomas Karrer about the origins of their new documentary The Power of Utopia: Living with Le Corbusier in Chandigarh, she exuberantly details the pivotal moment. It was on a 2012 flight to Bangalore, when she leafed through the architecture magazine Modulør External linkand happened upon “a very fascinating photograph,” taken in Chandigarh.

It started with a photo

“It was a fairly typical Indian street scene,” Bucher recalls, as the more taciturn Karrer scours his mobile phone in search of the picture. “A dusty road, women in saris, kids with colourful clothes riding bikes. But in the background, there was this huge concrete structure that looked completely out of place.”

“Like a cooling tower,” Karrer adds, before Bucher goes on: “This conspicuous contrast made me curious. I wanted to see the city with my own eyes.”

Eventually, Karrer holds up his phone to show me the picture in question. It’s a remarkable image, although the marks of Le Corbusier’s influence are somewhat less monumental or striking than I had been picturing during Bucher’s account.

Then again, the reaction is of a piece with the topic at hand, as Chandigarh is essentially one giant Rorschach test. Nicknamed “City Beautiful” in India, it has both been hailed as a masterpiece of urban planning and condemned as a bizarre act of cultural imperialism, an attempt to impose western ideas of progress on India only a few years after it had successfully deposed the British Raj.

Making utopia concrete

However, The Power of Utopia is as uninterested in reigniting this long-standing debate as it is in placing Chandigarh – which gradually made a name for itself as a liberal artists’ haven after its completion – in the turbulent context of current Indian politics. This is a deliberate choice, Bucher says: “I wouldn’t presume to be able to come in from the outside and pass judgement on the political situation in India.”

What The Power of Utopia sets out to explore through its collage of archival images, Le Corbusier quotes, interviews with local artists, architects, and urban activists, and architectural vistas – most of them filmed on the many cycling tours Karrer and Bucher took through the city during their eight-month artists’ residency – is the relationship between Chandigarh’s utopian blueprints and its existence as an actual physical space.

It may have been conceived by Le Corbusier as a person-shaped collection of residential areas, public institutions, parks, and industrial zones to foster city-living “in tune with nature” and help bring about “a better, more just, more harmonious world.”

But Chandigarh the idea eventually became – after the hands-on work of Le Corbusier’s cousin Pierre Jeanneret and a host of Indian architects, engineers, and construction workers – Chandigarh the city.

And it has developed accordingly: the original city sectors have become indicators of income level; the green belt that surrounds it limits the potential for expansion, causing the cost of living to explode; and the original concrete buildings, after decades of extreme heat and dozens of monsoon seasons, are starting to show their age.

Anachronistic monument

As local architect Siddhartha Wig says in the documentary, “Chandigarh is becoming a museum,” a monument to the revered figure of Le Corbusier, and to the potentially anachronistic dreams of mid-century European architecture. “In conception, it was utopian,” Wig adds. “What has turned out, I’m not so sure is fully utopian.”

Yet The Power of Utopia ultimately argues that Chandigarh, as it exists today, is nevertheless a testament to the experiment’s success. “We’ve taken a foreign master and made him our own,” Wig muses towards the end of the film. Modern Chandigarh is, first and foremost, the work of its residents.

Whereas a more conventional Swiss production about the city might have stressed its “Swiss credentials” – both Chandigarh and Le Corbusier were featured on the ten-franc banknote from 1997 to 2017 – The Power of Utopia confines the legendary architect to the margins of history throughout: his is a ghostly presence, not a defining one.

While this distancing gesture may be partially due to his contradictory politics and his often-discussed engagements in fascist regimes – “only Le Corbusier knows what Le Corbusier believed,” Bucher quips – it could also be part of a tentative move away from some of the marketing considerations that have traditionally governed documentary filmmaking in Switzerland. Received wisdom holds that in order to be relevant enough for funding and a wide cinematic release, films should strive to focus on a topic’s “Swissness,” no matter how tenuous.

And even though there is an echo of that in The Power of Utopia – the unwieldy subtitle is an unmissable tell – it gently resists the practice through its narrative framing. As with the titular city itself, Le Corbusier may be where the story starts. But everything else hinges on the people of Chandigarh.

Edited by Virginie Mangin and Eduardo Simantob/gw

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.