Esperanto – more than a language

Esperanto is underpinned by a desire to bring people together and by humanitarian ideals.

Little wonder, then, that this international language has a long relationship with the Swiss city of Geneva.

“Behind Esperanto there is the idea of solidarity,” says Claude Piron, a leading authority on Esperanto and resident of Gland, a town located between Geneva and Lausanne.

He has written six novels and several short stories in his beloved Esperanto, as well as numerous articles about the language itself.

“I learned it when I was 12 and I have always remained faithful to it because it has brought me so many friendships,” he says.

Esperanto – underpinned as it is by a culture of tolerance and respect for others – is an artificial language, invented by an individual frustrated at the animosity and lack of understanding among the four ethnic groups who inhabited his city.

He who hopes

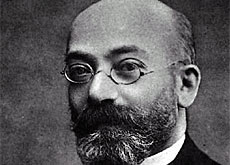

Louis-Lazare Zamenhof, who lived briefly in Geneva, was a Jew from Bialystok, a city in present-day Poland where, Poles, Russians, Germans and Jews lived in far from peaceful coexistence.

In 1887, he created Esperanto – “he who hopes”, in his new language – as a way of bringing people together and ending prejudice and misunderstanding.

The ideals of solidarity, international understanding and respect for others meant there were obvious links between the language and the Red Cross movement.

It is no coincidence that the first international Esperantist Movement was created in Geneva – home of the Red Cross – nor that those behind it were heavily involved in humanitarian work during the First World War, tracing missing persons in enemy territory and visiting prisoners.

Just as the Esperantists went from promoting linguistic ideals to human rights and civil liberties, so too did the Red Cross promote Esperanto.

In 1921, the 10th International Conference of the Red Cross recommended that all National Societies encourage their members to learn Esperanto.

After the First World War, Esperanto might have been adopted by the League of Nations as an official language of international relations, had it not been for opposition from France, and – to a lesser extent – Britain.

But by the end of the Second World War, Nazi and Stalinist persecution had led to a decline in the use of Esperanto.

On-line Esperanto

Very much a product of its time, Claude Piron is nevertheless optimistic about the language’s future.

“The Internet seems to have been designed for Esperanto speakers,” he says, pointing out that websites and chat rooms devoted to the language have proliferated on the web.

The worldwide Esperanto population numbers some two million speakers, but is extremely scattered. “It’s frustrating to have an international language and not be able to speak it regularly,” Piron says.

“The internet has changed all that. You can have discussions as you would in a bar.”

The presence of so much information about Esperanto on the web, he says, helps to shatter the misconceptions and prejudice that surround the language: that Esperanto is rigid, unchanging and not as expressive as one’s mother tongue, that it is essentially a European language, and that an international language -English – already exists.

“The idea that English is spoken everywhere is a tremendous exaggeration,” Piron says.

The Esperantists’ argument is well-practiced: once you leave business and tourist centres, the vast majority of people do not speak English, and those that do find it difficult to master.

“I’ve always been amazed at the masochism of human beings with regard to language,” says Piron, himself a former United Nations translator.

Logical

“After six months of Esperanto I was more fluent than after six years of English,” Piron says. That is because Esperanto is a logical language. “Once you know a rule, you can apply it across the whole language,” he adds.

Unlike in other languages, there are no irregular verbs and no genders, while all plurals are formed in the same way. Word order is fluid. Esperanto was constructed using the best elements of other languages.

If it sounds Latin-based, that is because 60 per cent of its vocabulary comes from Romance languages, while 30 per cent is of Germanic origin and 10 per cent Slavic.

But there are also eastern influences – Esperanto is very similar to Mandarin Chinese in the way it “builds” words in a predictable way from an unchanging stem.

Another advantage of Esperanto, Piron says, is that it is free of the cultural and historical baggage that comes with English, or other national languages, which many equate with colonial arrogance.

“There is an inhibiting factor when people from different backgrounds are forced to speak the language of a particular nation. There is a filter to your spontaneity and emotions,” he says. “In Esperanto, this filter does not exist.”

“It would change international relations if people could speak to each other on an equal footing, with a complete lack of inhibition.”

swissinfo, Roy Probert in Geneva

There are an estimated two million Esperanto speakers.

Louis-Lazare Zamenhof unveiled his international language in 1887.

The Universal Esperantist Association was created in Geneva in 1902.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.