How a couple of sausages triggered the Swiss Reformation

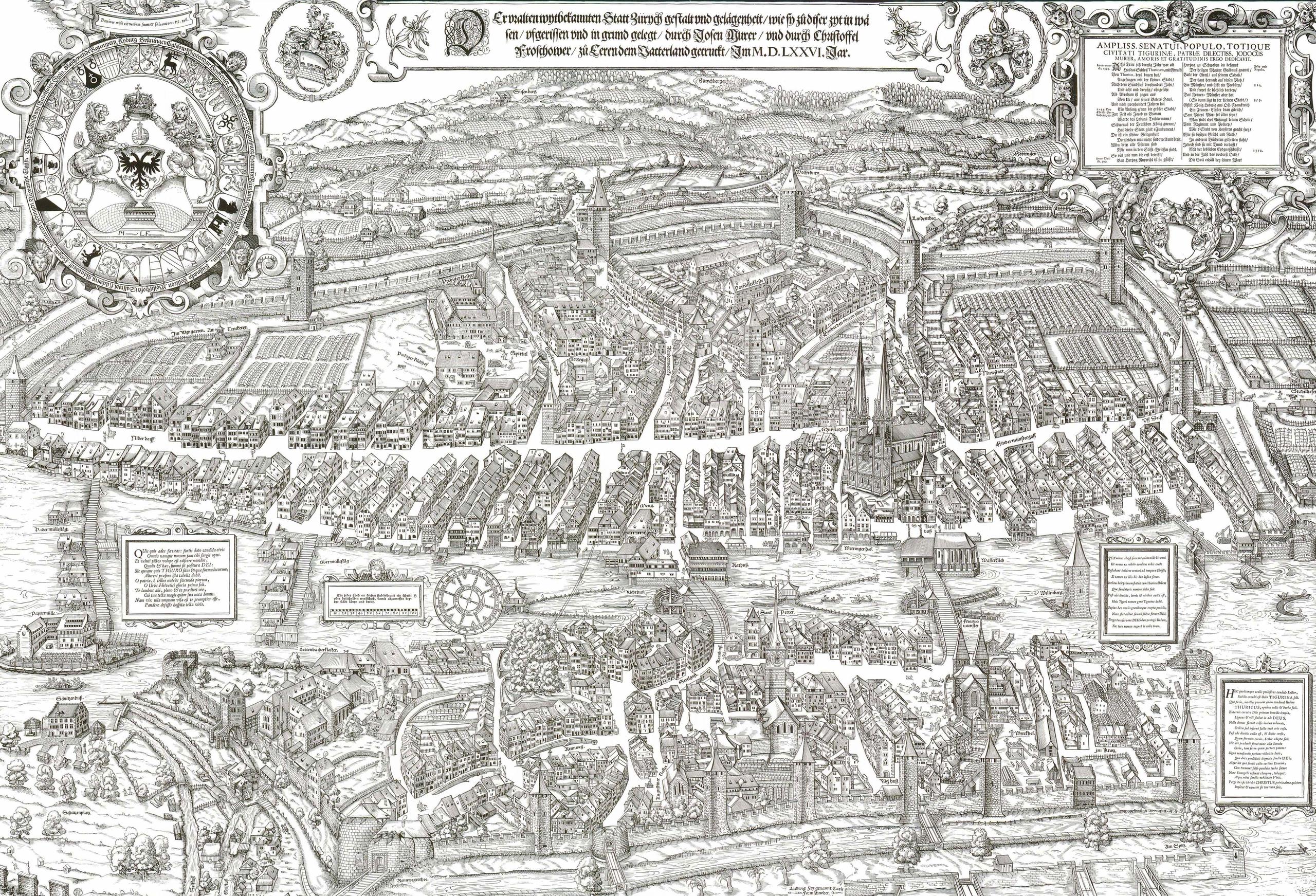

The time: March 9, 1522, the first Sunday of Lent. The crime scene: a printer’s workshop in Grabengasse, just a stone’s throw from Zurich’s city walls. The first in a series of swissinfo.ch articles marking 500 years of the Reformation is a sizzling thriller.

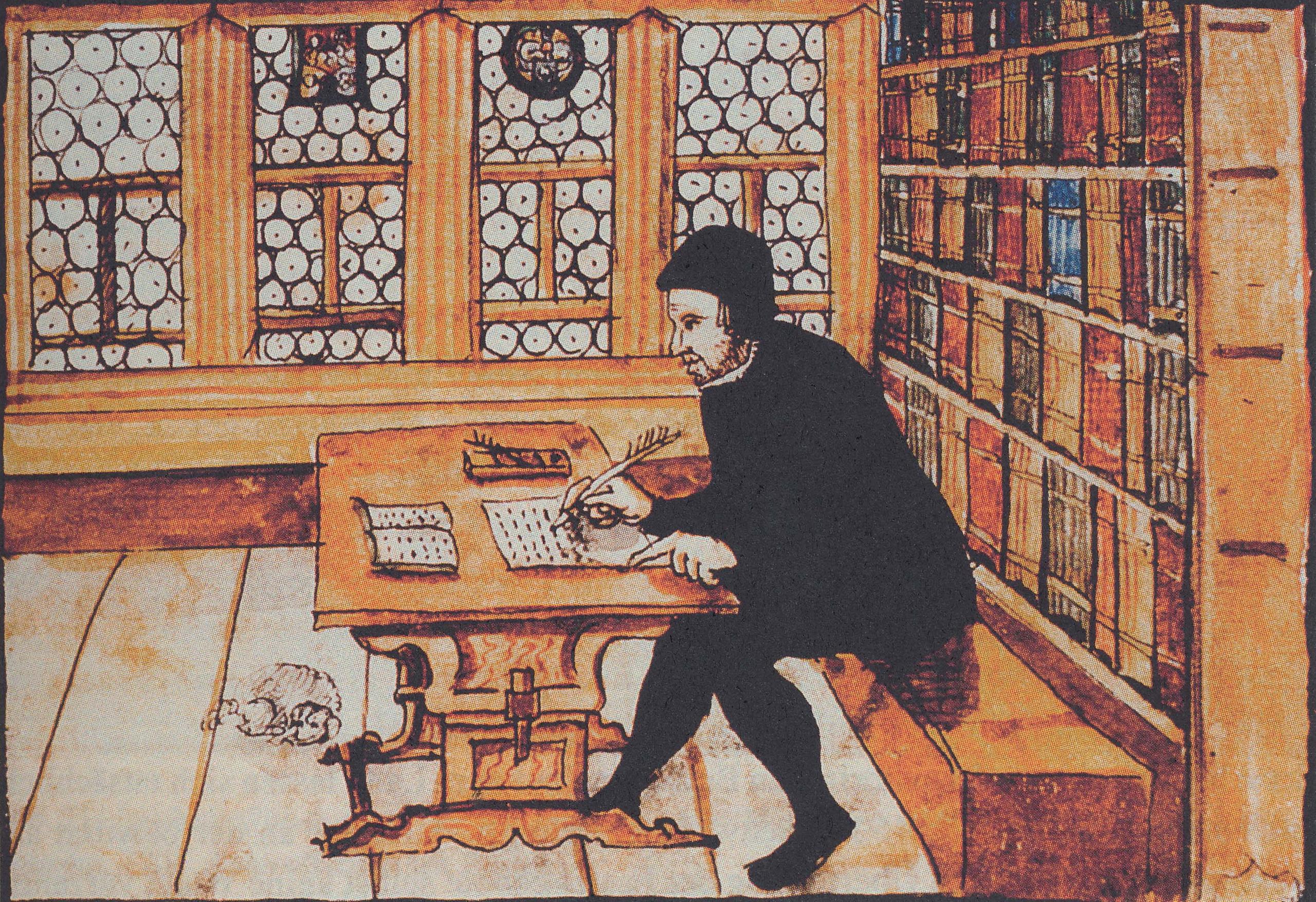

It’s late afternoon and a dozen men have gathered between printing blocks and type boxes to challenge the Catholic church and the city dignitaries. The owner of the building, Christoph Froschauer, is there. His workshop carries out all the printing for the Zurich government.

This historical account is part of a series of swissinfo.ch articles marking 500 years of the Reformation. The origin of the Reformation is generally considered to date back to the publication in Germany of the Martin Luther’s 95 Theses on October 31, 1517.

Also present are two priests. One is 38-year-old Huldrych Zwingli from Toggenburg in canton St Gallen. After studying in Vienna and Basel, he was a priest in Glarus and the place of pilgrimage, EinsiedelnExternal link. He was then called to the GrossmünsterExternal link church in Zurich, where he quickly gained a reputation as a talented but unconventional preacher.

The other is Leo Jud from Alsace, who in 1519 became Zwingli’s successor in Einsiedeln. He is almost as old as Zwingli and is considered his most trusted confidant.

In addition to theology, the trades are also represented: Hans Oggenfuss, a tailor, Laurenz Hochrütiner, a weaver, and shoemaker Niklaus Hottinger are already known in Zurich as reform-minded hotheads.

They would achieve notoriety far beyond Zurich a year later when, in their religious zeal, they pull down a wayside cross at the city gates and chop it into pieces.

The fourth tradesman is Heinrich Äberli, an equally radical baker. Only four days previously, on Ash Wednesday, a day of atonement, intercession and fasting, he clashed head-on with pious Catholics. In the bakers’ guild house he ostentatiously ate a – probably homemade – roast, in the full knowledge that eating meat during Lent was forbidden by the authorities, who actively enforced the ban.

It was a huge provocation – no one in Zurich had ever seen anything like it – but it was a period of religious unrest.

Private matter

The men in the printing workshop all want to break the fasting rules as well, forcing the authorities and the church into a corner. Together, they eat two smoked sausages cut into small pieces and ensure that news of their act of rebellion spreads in town.

Zwingli is the only person who doesn’t eat anything. His job is to justify the provocation theologically. Two weeks later, he delivers an inflammatory sermon, “On food choice and freedom”, in which he claims the Bible doesn’t contain any dietary rules. It’s not a sin to break the fast, he continues, and can’t therefore result in punishment by the church.

Fasting is a private matter, he says. “If you want to fast, go for it; if you prefer not to eat meat, don’t, but grant Christians their freedom.”

Just three weeks later Zwingli’s sermon has been printed by his friend, Christoph Froschauer. The scandal is now perfect and Zurich is up in arms. Fights break out in taverns between Zwingli’s fans and opponents; the rumour circulates that fanatics want to kidnap him and drag him to the bishop’s seat in Constance to be held to account by his superior.

Sausage Revolution

For Zwingli, breaking the fast is a wild success. When the Bishop of Constance sends a delegation to find out what’s going on, Zwingli sits at the negotiating table as an equal partner and distinguishes himself as instigator of the reform movement.

Froschauer, however, who is responsible for all the government printing, has to apologise for his indiscretion. Nevertheless, before the Frankfurt book fair he claims he is forced to work “day and night, workdays and holidays” so that he doesn’t end up “eating gruel”.

But the Affair of the Sausages doesn’t do him any harm, since he is seen to be on the right side of history, publishing a few years later the first complete Reformation Bible.

One year after the gathering in Grabengasse, all fasting is abolished in Zurich. The government thus not only follows Zwingli’s interpretation of the Bible, but at the same time breaks with the tradition of the Catholic church.

While the Reformation in Germany began with 95 learned theses, in Switzerland it all started with a roast and a couple of sausages.

Regula Bochsler

Regula Bochsler studied history and political science at the University of Zurich.

She has worked for many years as an editor, journalist and presenter for Swiss public television, SRF. She has made ten or so telelvision programmes on history as well as putting on exhibitions.

Her books include “The Rendering Eye. Urban America Revisited” (2013), “Ich folgte meinem Stern. Das kämpferische Leben der Margarethe Hardegger” (I followed my star. The combative life of Margarethe Hardegger) (2004) and “Leaving Reality Behind. etoy vs eToys.com & other battles to control cyberspace” (2002).

(Translated from German by Thomas Stephens)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.