Getting the vote: When women campaigned against women

March 8, International Women’s Day, is when women from all over the world proudly come together in solidarity. Surely this would always have been the case regarding the right to vote? Not in Switzerland.

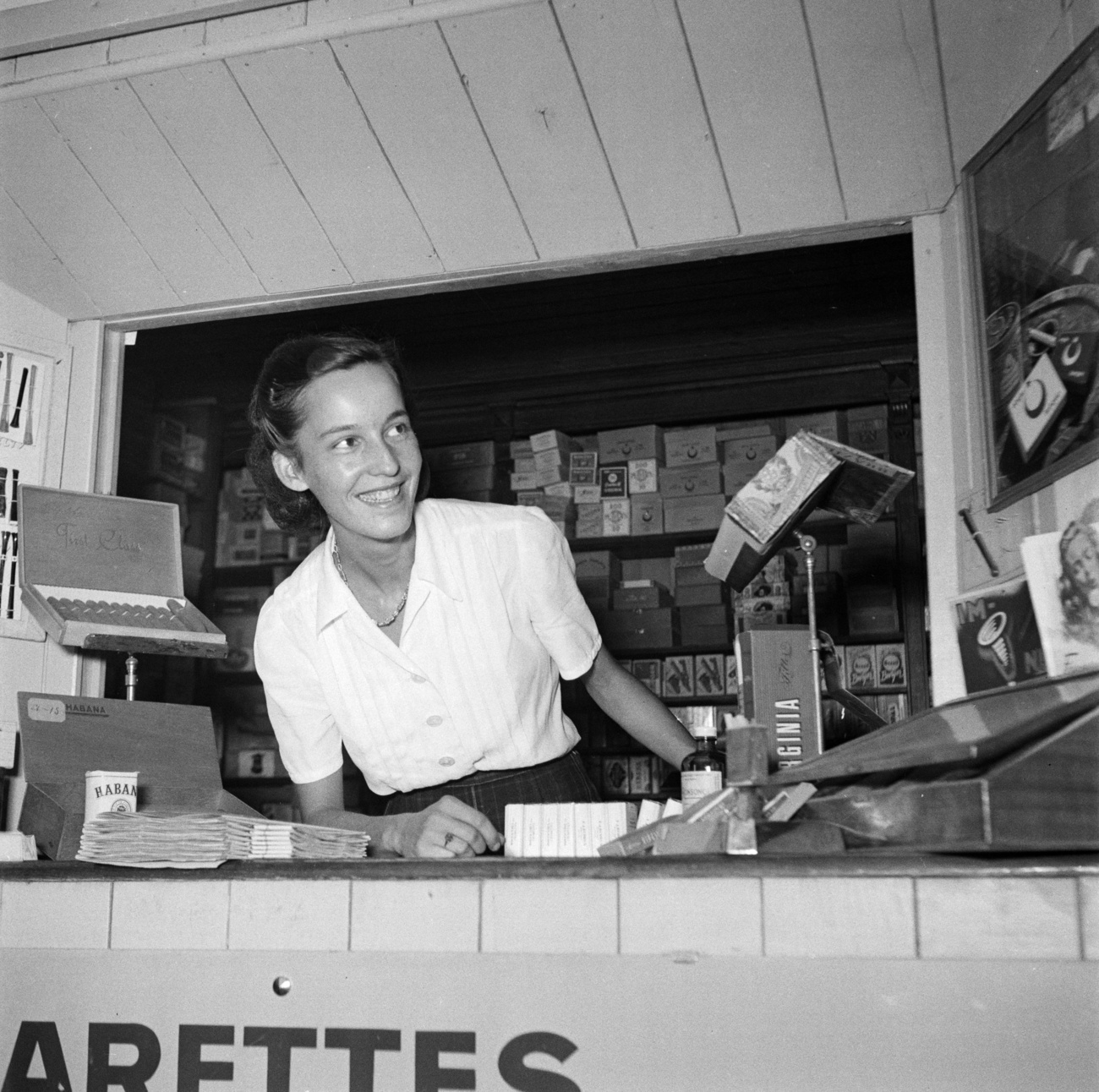

One woman who did not believe women should have the right to vote is Rosmarie Köppel-Küng, who joined the League of Swiss Women against Women’s Suffrage at the end of the 1950s.

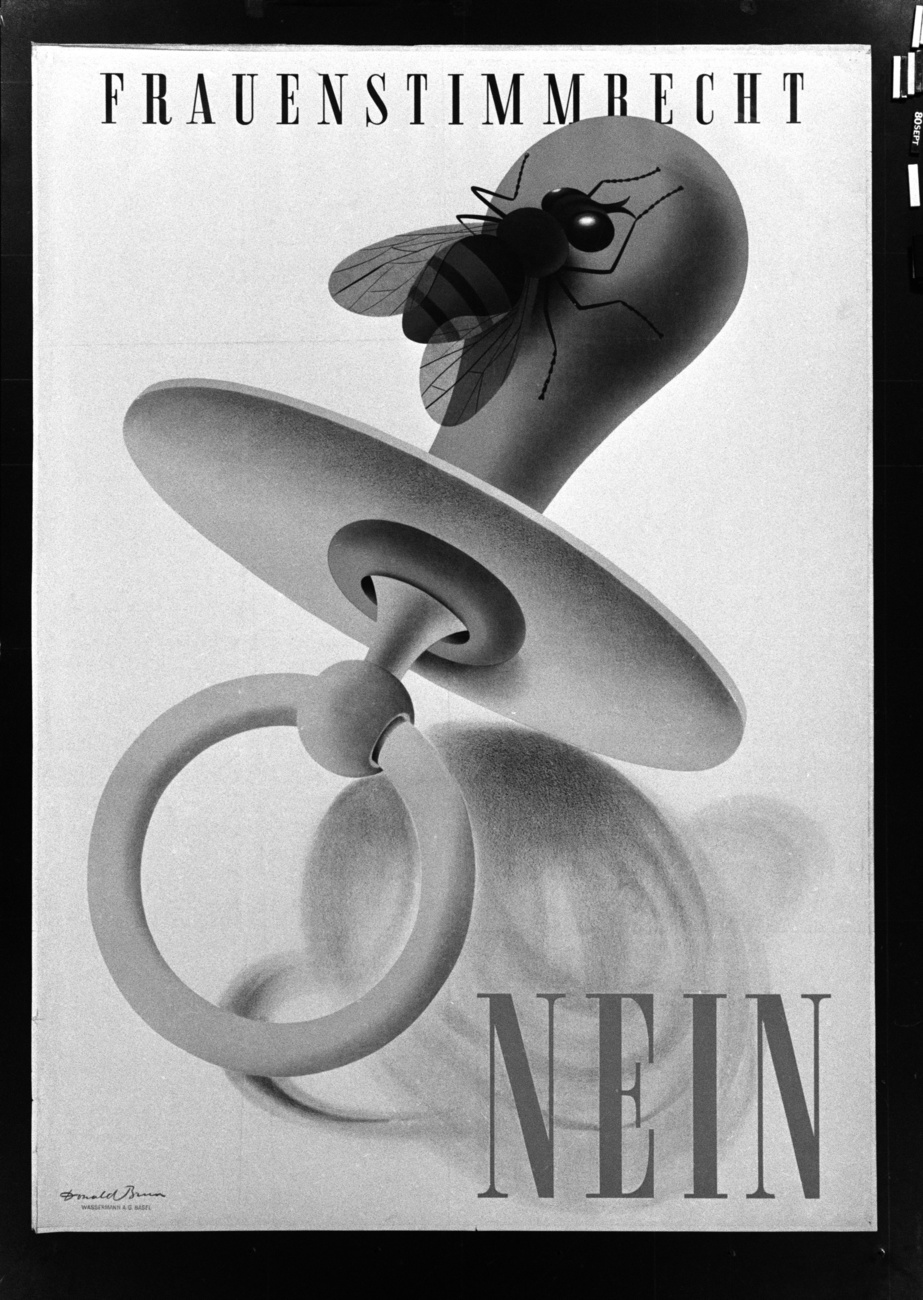

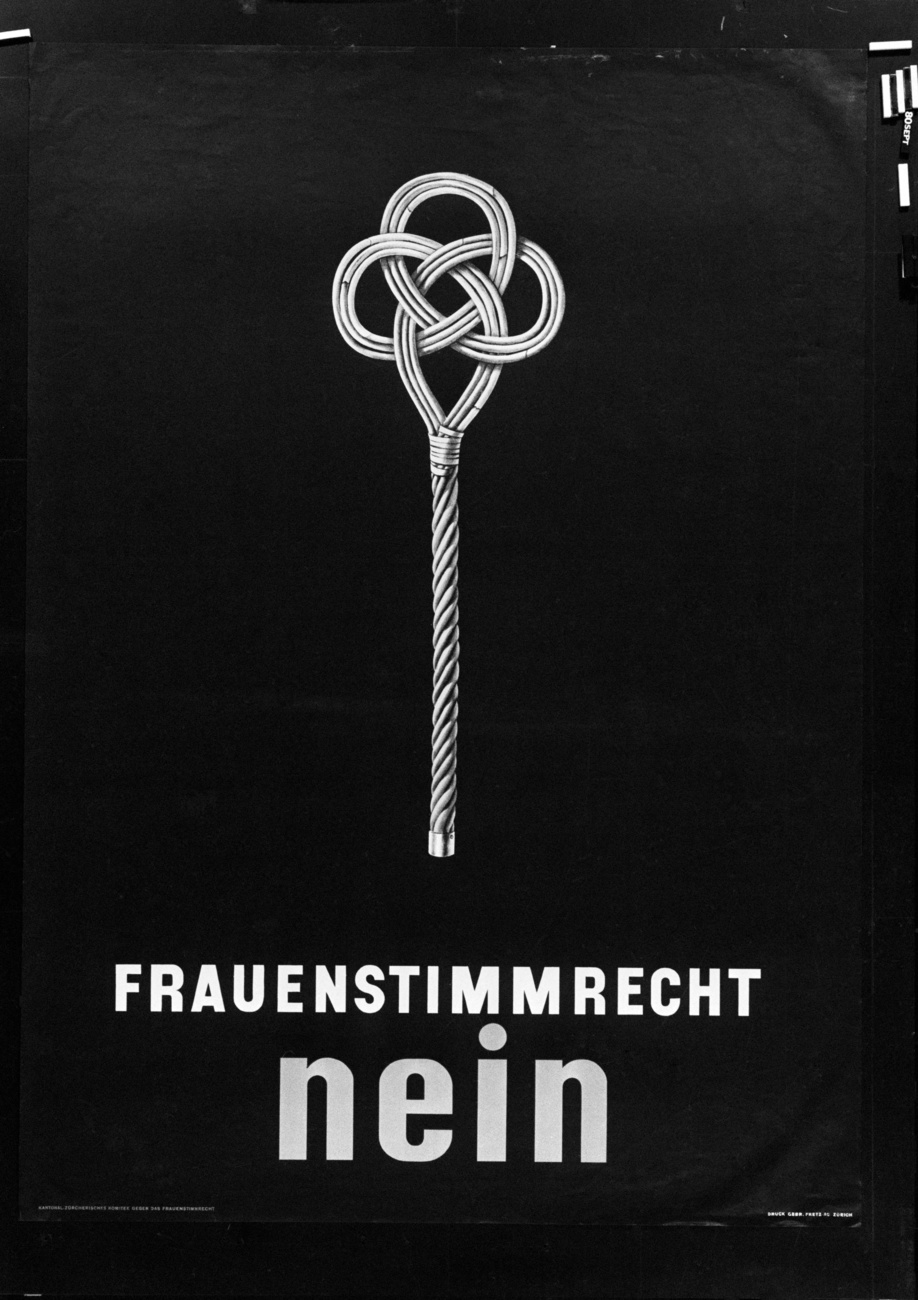

A paradox ensued: female opponents of women’s suffrage found themselves having to be politically active – in order not to be politically active. There were limits to what they could do, though. While supporters were able to attract media attention with creative and sensational activism, opponents were limited to adverts, roundtable talks and podium discussions. They let themselves be carried away by the spirit of the times and tried their hand at coarse rhetoric, but then soon backtracked as this wasn’t considered very feminine.

Opponents argued primarily with the natural distribution of roles. Anti-suffragette, Gertrud Haldimann-Weiss studied pharmacy at the University of Bern and graduated in 1930. She wrote: “Our true task is to serve, to give, to give thanks, not to rule, to demand or to coldly calculate.” While the husband was responsible for political decision-making and affairs of the state, the wife took care of the home – always under the supervision of her husband’s “fatherly authority”, of course.

A letter to a Zurich group of female opponents of voting rights said: “The rejection of political equality among women, however, is based on the certainty that what they do as wives and mothers, as sisters and daughters, as professional employees, has at least as high a rank as the direction of the affairs of state.”

Men who campaigned for equality were often portrayed as weak. “I sometimes almost explode,” Haldimann-Weiss wrote. “But I often grind my teeth when I see how men put up with such things.”

Despite Switzerland’s slow progress in making it legal for a woman to vote, in other countries that had already set the tone for liberation, like the UK and the US, there was a tendency in the 1960s to deplore the effeminacy of men and their integration into domestic work. In the 1955 film Rebel without a Cause there is a sceneExternal link in which the father runs around in an apron serving the family – no wonder it doesn’t end well with James Dean!

These views were notably upheld by Harvard-educated lawyer and author Phyllis SchlaflyExternal link, who campaigned against the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) and argued that women should stay at home. Paradoxically, Schlafly, who was also anti-Communist, was highly politicised and ran for the Republican Congress in 1952. She also later claimed that the ERA would lead to unisex toilets and the promotion of gay marriage – a visionary, no less.

Despite the emphasis on domesticity, many opponents to women getting the vote could afford domestic help and came from wealthy, middle-class backgrounds. They simply had an interest in maintaining the status quo. Thus, during the Cold War, the desire for gender equality was also equated with the “egalitarianism” of communism. Even knowing that the status of women behind the Iron Curtain was somewhat different, the rejection of women’s rights was justified by the fight against communism.

In Switzerland, it was feared that women’s suffrage would shake the nation and make it vulnerable to leftist subversion. One scenario, for example, was that women’s suffrage could target the military and weaken the country. This also speaks to a fundamental distrust that other women will act manipulatively and irrationally.

Calling oneself an anti-feminist is still a common statement today, referring mostly to issues of everyday gender culture: Who looks after the children? Who works part-time? But the idea that women should give up the vote has become unthinkable. Even Rosmarie Köppel-Küng said in an interview more than 50 years later: “Today I would be for it.”

This text is based on the licensed work of historian Daniel Furter, ‘Die umgekehrten Suffragetten, Die Gegnerinnen des Frauenstimmrechts in der Schweiz von 1958 bis 1971’ (The reversed suffragettes, the female opponents of women’s suffrage in Switzerland from 1958 to 1971).

More

Huge turnout for women’s strike in Switzerland

More

The long road to women’s suffrage in Switzerland

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.