Giacometti – a communist, but above all free

An exhibition at the Liberation of Paris Museum is displaying portraits by Alberto Giacometti of Henri Rol-Tanguy, a communist Resistance fighter. This year, in France and elsewhere, the public has rediscovered the artist from southeastern Switzerland.

After spending the war in Switzerland, in September 1945 Giacometti (1901-1966) returned to Paris and his small studio on Rue Hippolyte-Maindron. “Since my last letter, so many things have happened to me that have prevented me from writing to you or doing anything at all,” he wrote to his future wife, Annette Arm. “For the past 15 days I have been working as never before; I have worked day and night and I just keep going. I am no longer interested in anything else and I no longer read the newspapers.”

His friend, the communist poet Louis Aragon, had introduced him to Rol-Tanguy (1908-2002), the man of the hour in Paris. Hero of the Resistance and leader of the French Forces of the Interior during the liberation of the capital, Colonel Rol readily spent endless sessions with the sculptor, “on his uncomfortable chairs, during which he forbade the colonel to make the slightest movement”, says the Liberation of Paris MuseumExternal link, which is exhibiting these little-known works.

The young military officer and the artist with the tousled hair, scarf hastily tied over an old jacket with turned-up collar – too obsessed with his art to be truly bohemian – immediately warmed to each other. “I like him a lot and he has a very beautiful head […], the bearing of Napoleon’s young generals and very bright and intelligent,” Giacometti wrote to Annette.

‘Fellow traveller’

In the Paris of the day it was best to be either a communist or a Gaullist. Giacometti did not have a French Communist Party (PCF) card but his past made him a highly respectable “fellow traveller”, as intellectuals and artists committed to the “cause” were then called. He was a longstanding friend of Aragon, the “official” and talented PCF poet, who was prepared to cover up all the horrors of Stalinism.

Before the war Giacometti had joined the Association of Revolutionary Writers and Artists, which brought together PCF sympathisers. In a letter to his surrealist mentor André Breton he wrote: “For my part, I have made drawings for the struggle, drawings on immediate issues, and I intend to continue. I would do everything I can in this way to help the class struggle.”

In one of these drawings, as later described by Aragon, the Swiss artist depicted, in blue ink, “a Japanese soldier with one foot on Japan, the other on China, and a curved sabre in each hand, threatening the border post with the USSR: it was intended to be carried in a demonstration, although in the end it was never used”.

Small plaster heads

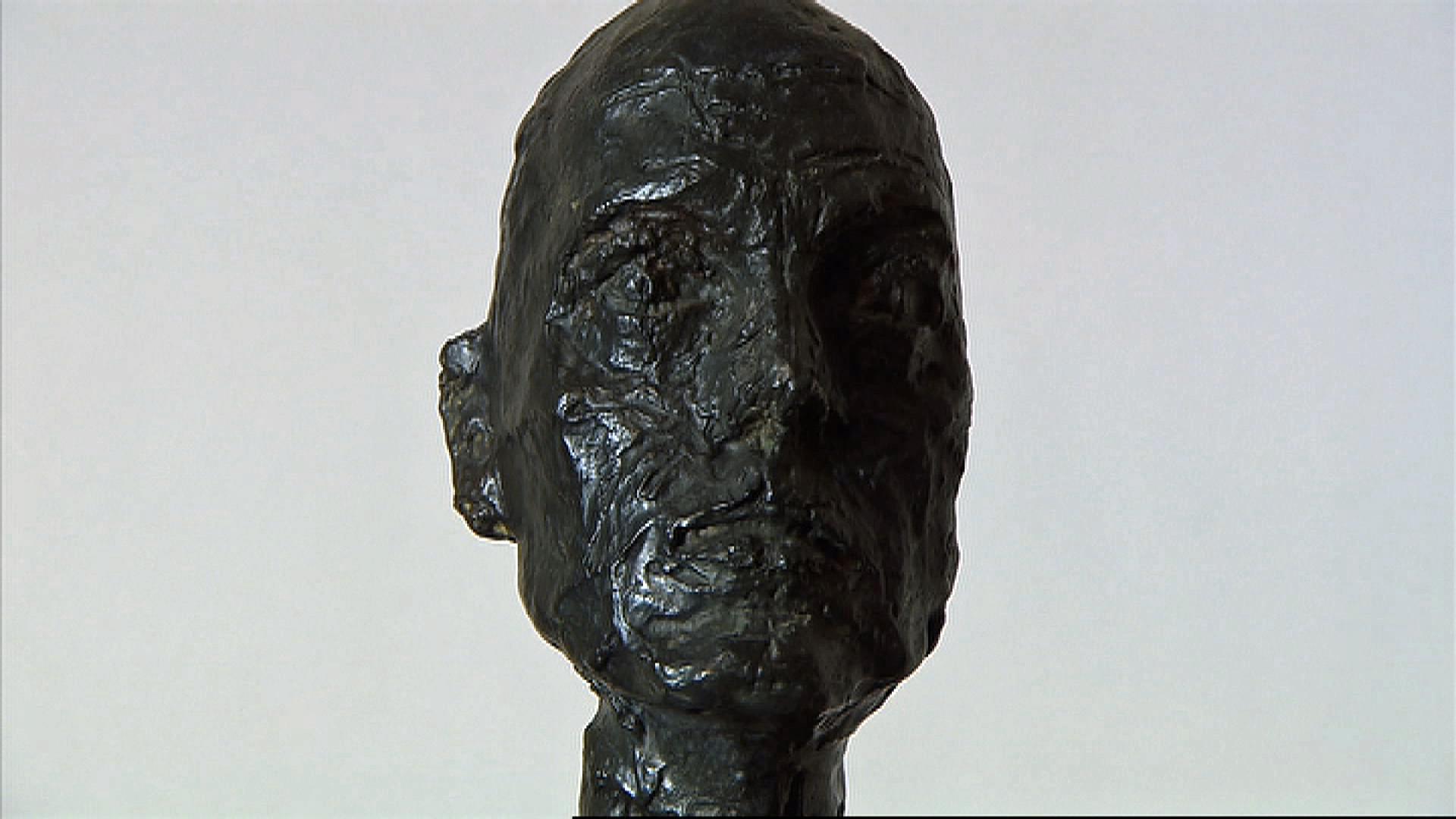

In short, Giacometti had proved he was red enough to sculpt the profile of the communist hero. One might therefore have expected a glorious portrait of Rol-Tanguy, pistol in hand and red flag aloft. However, Giacometti remained true to himself. There was no question of him becoming the regime’s official artist. What emerged instead were tiny plaster heads, mounted on a base or just placed on a nail, the colonel’s cheeks sometimes notched with penknife cuts.

Rol-Tanguy was not precious. Giacometti “literally ‘delved’ into your features. It felt as if his hands, which were on the portrait he was making, were actually touching my face”, he later recalled.

For Giacometti, art came first and then the cause. When the party wanted to erect a monument to the Resistance hero and martyr Gabriel Péri, the Swiss artist used the skinny figure of The Walking Man, which he subsequently returned to extensively in different ways. This sparked anger and incomprehension among the communists, who saw it as an emaciated survivor of the Nazi camps.

The Liberation of Paris Museum is in Paris’s 14th arrondissement, a stone’s throw from the small but delightful Giacometti InstituteExternal link and just around the corner from where the artist had his studio on Rue Hippolyte-Maindron, which now bears a commemorative plaque. The museum offers visitors the possibility to enter the underground shelter where Rol-Tanguy planned the French – and Allied – victory.

A summer with Giacometti

Giacometti the crypto-communist, the fan of Egypt, the man from Stampa and his family, his complete works, the artist as photographed by Peter Lindbergh – as art venues around the world re-opened after the lockdown, it was difficult not to meet the man from Graubünden’s Val Bregaglia.

At the Fondation MaeghtExternal link in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, at the Grimaldi Forum in Monaco, at the Giacometti Institute in Paris, but also in Porto: throughout the summer and autumn Giacometti was everywhere – often accompanied by record visitor numbers. French newspaper Le Monde saw it as the artist’s “return to grace”, after years of coolness and reservation from specialists towards a man who was suspect because he was too… free.

“Giacometti is very popular with the general public,” summed up Catherine Grenier, director of the Giacometti Foundation and the artist’s biographer. “Maybe because he didn’t seek glory, luxury or trips abroad but instead lived very simply. Anyone could come to his studio. He was often seen at the local café and was very easy to talk to. It’s that simple lifestyle that makes him a guiding figure.”

Thanks to the Giacometti Foundation, which is lending more and more works to museums, “the public can discover the breadth of his work, which until now was mainly limited to The Walking Man,” Grenier added.

Rol-Tanguy by Giacometti, Liberation of Paris Museum. Until January 30, 2022.

(Translated from French by Julia Bassam)

More

Why Alberto Giacometti’s art is so successful

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!