Hannah Villiger – pioneer of selfies with a Polaroid camera

The Istituto Svizzero in Rome is hosting a major exhibition on Swiss artist Hannah Villiger, who spent time in the city in the 1970s. It offers a glimpse into the extraordinary world of Villiger, who, despite using Polaroids, considered herself more of a sculptor than a photographer.

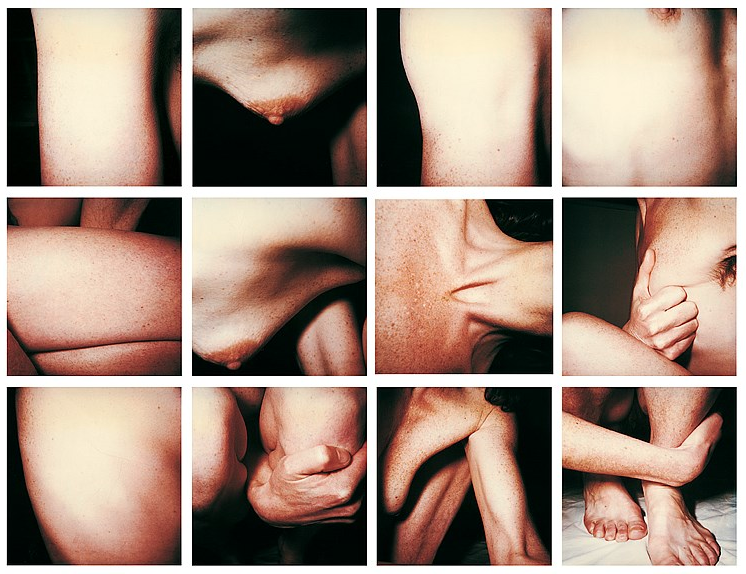

It’s the first time the artist, whose large-format photographs often featured fragmentary close-ups of her own body, has been given a solo show in Italy. The Istituto Svizzero, the Swiss cultural centre in Rome, is hoping that the Works/Sculptural exhibitionExternal link will help raise awareness of Villiger’s work internationally. The artist died in 1997, aged just 46.

About the show

Works/Sculptural runs until June 27, 2021 at the Istituto Svizzero in Rome. Curated by Gioia Dal Molin, the exhibition will be complemented by a book released with Mousse Publishing in summer 2021, with contributions by Elisabeth BronfenExternal link, Dal Molin, Quinn LatimerExternal link and Thomas SchmutzExternal link.

The exhibition looks at Villiger’s whole career, with a special focus on her stint as a resident at the Swiss cultural centre at the Villa Maraini from 1974-6.

The exhibition looks at Villiger’s whole career, with a special focus on her stint as a resident at the Swiss cultural centre at the Villa Maraini from 1974-6.

Villiger came to Rome after graduating from the School of Applied Arts in Lucerne and only left in 1977, having stayed on after her residency. These years were key in shaping Villiger’s artistic imagery. She drew inspiration from the Roman cultural scene, including the radical Arte PoveraExternal link movement (which used unconventional processes and “everyday” materials).

During this time, Villiger also participated in important European art events like the Biennale in Paris in 1975. Here she represented Switzerland alongside artist John Armleder and painter Martin Disler.

Reconquering the body

Villiger also sharpened her style while in Rome. She showed interest in drawing and performance. Her move towards photography became definitive in the 1980s, after she discovered the immediacy of the Polaroid camera. It became her signature working tool.

Health problems may have nudged her along when making the transition to photograph (she suffered from a severe case of tuberculosis). Using a Polaroid camera meant that she did not have to go to the photo lab to develop the negatives. She appreciated the speed with which the photos were made and could be composed into a work. This was a counterpoint to the changing and fragile nature of her daily life.

The artist’s body becomes the main element of her work and investigation, around which Villiger developed an almost ritual-like practice, marked by work sessions which took place inside an “arena” – a white sheet stretched out on the floor. Here body forms become objects undergoing a process of metamorphosis. These experiments were fully in line with the artistic practice of the time, in which the traditionally masculine genre of the self-portrait was reconquered by fundamental female experiences, as seen through fellow artists Eleanor Antin, Ana Mendieta and Cindy Sherman.

During the 1980s and 90s, Villiger exhibited her works at important European institutions such as the Kunsthalle Basel (1981 and 1985), the Centre Culturel Suisse in Paris (1986), the Museum of Contemporary Art in Basel (1988/9) and the Frankfurt Art Association (1991).

In terms of Villiger’s artistic development, her photographs produce results that are extremely fragmented, almost abstract, that are radical in making the body seem unrecognisable, even if it is the main subject of the works.

Last years

Villiger spent her final years in Paris, which had been her home since 1986. During this period, she participated in the 22nd San Paolo Biennale (1994) in which she represented Switzerland along with the artist Pipilotti Rist (Grabs, 1962). The event was one of the most popular in the Brazilian Biennale’s history and featured names such as Piet MondrianExternal link, Lucio FontanaExternal link, Robert RauschenbergExternal link, Gerhard RichterExternal link and Rosemarie TrockelExternal link.

Villiger kept on producing “blocks” of Polaroids, despite spells of bad health and hospital stays, right up until spring 1997. She died of heart failure in August of the same year, just days after returning to Switzerland.

The show at the Istituto Svizzero in Rome alternates large photographic works with Villiger’s notes, research materials and drawings. The show’s takes on the feeling of a diary in which the borders between works and notes become blurred, forming a complete narration.

It starts with Villiger’s works from the 1970s and ends with her photographic oeuvre from her final years.

Not photographic but sculptural

Representation of the body remains a thread through the exhibition, with a succession of works showing the move towards fragmentation set against the eclectic surroundings of the Villa Maraini. There are also works which do not deal with the body – such as Von der Terrace, der Baum (1984/5) in the first room of the exhibition as well as a selection of “discarded” Polaroids in the last room in which views of trees appear. These show the visitor the real perimeters of the artist’s investigation, highlighting how her gaze meticulously scanned what was in her immediate vicinity.

The plasticity of the photographic image, generated through the two-dimensional medium of photography, is a fundamental part of the artist’s oeuvre – to the point where she herself defined her works as “sculptural”. So close ups of the body become spatially twisted architectures, moonscapes, hills and depressions.

These ruptures and dissimulations show a desire to reappropriate the body, from a female viewpoint. Through her images, Villiger rejects being viewed as an object rather than a subject and being scrutinized rather than being the scrutinizer.

“Through constant repetition,” she once wrote, “my body becomes ‘a body’.” Her approach could be seen as wanting to create a universal body, unrecognisable and therefore impregnable.

This gaze, which at once segments, distorts and brings together, could be considered the true heart of the exhibition. Its evolution is mirrored by the chronology of the exhibition which also captures the infinitesimal distances travelled, showing how the artist, by moving just a few steps, always sought and found the essence and proportionality of the world.

(Adapted by Isobel Leybold-Johnson, edited by Dominique Soguel-dit-Picard)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.