Hodler sketches offer intimate insights

Swiss artist Ferdinand Hodler is perhaps best known for his paintings and frescos –figurative landscapes and portraits - but he was also a prolific draughtsman.

Some 120 of his little-known drawings, sketchbooks, posters and etchings are currently on display at the Geneva Art and History Museum’s graphic art department until February 19, 2012.

Together with the Kunsthaus in Zurich and Bern’s Kunstmuseum, Geneva has one of the world’s most important collections of Hodler works, comprising 144 paintings, 800 drawings and 241 sketchbooks.

But for Caroline Guignard, co-curator of the new “Ferdinand Hodler: works on paper”, Geneva’s is the most significant.

“Zurich has 1,500 drawings but we have sketchbooks dating from 1890 to 1917 and drawings that span his entire career,” she told swissinfo.ch.

Hodler, who lived from 1853 to 1918, is generally regarded as one of Switzerland’s most important artists.

“Hodler considered himself a painter but he was very aware of the importance of drawings. All of his works are the fruit of a colossal preparation process,” said Guignard.

For each of his hundreds of paintings, Hodler produced dozens of sketches.

Classical training

The poor budding artist travelled to Geneva at the age of 18 to learn his trade under the guidance of Barthélemy Menn, a student of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and a professor at the Academy of Art.

“He had a classical training,” said Guignard. “Drawing was part of the creative process. It was like a work in progress.

“He would throw down his first ideas and compositions as sketches in a very spontaneous and intuitive way. This would be followed by closer observations of figures and structures which would be fleshed out.”

The artist never sold his drawings, nor exhibited them, but occasionally gave them away as presents. After his death in 1918 the Hodler family inherited a huge collection of drawings. In the 1950s the Geneva Art and History Museum was able to acquire 241 sketchbooks for its collection thanks to the insistence of art historian Jura Bruschweiler.

Displaying all of them at the graphic art department would have been impossible, so Guignard and her colleague Christian Rümelin had to make a judicious selection dividing the exhibition into four sections: symbolic subjects, portraits and self-portraits, historic Swiss scenes and various.

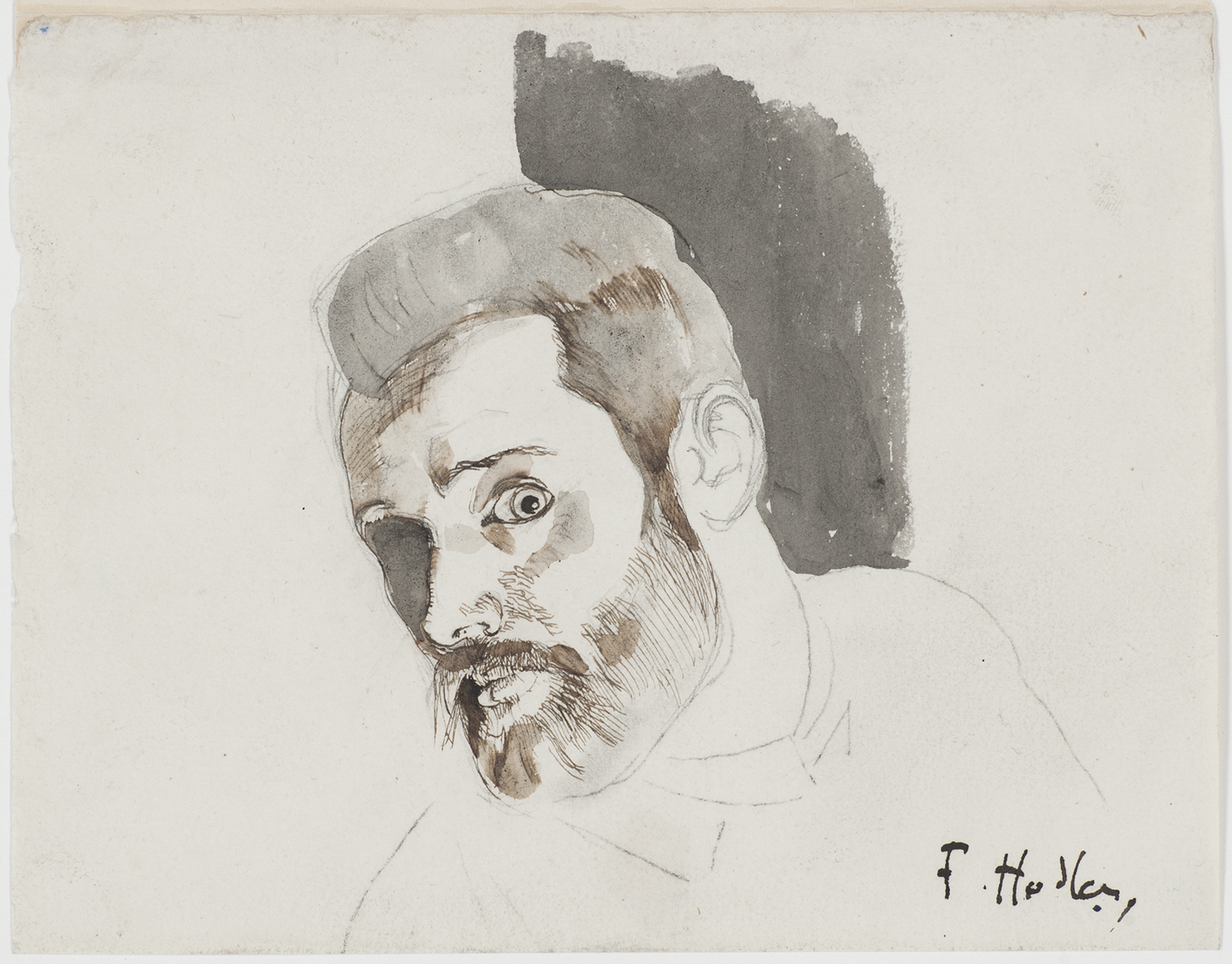

Steely gaze

Entering one of the first rooms your eyes are immediately drawn to the intense steely gaze of the young up-and-coming artist staring out from an 1891 portrait.

“He had just triumphed in Paris with his controversial painting “La Nuit” [which was banned in Geneva for its “obscene” nude scenes]. You see an artist full of ambition, very affirmative,” said Guignard.

The walls are covered with other portraits of Hodler from throughout his career. The Bernese artist had the amazing ability to combine the traditional and the modern: one colourful abstract sketch of the bearded artist from 1916 looks remarkably like a Matisse and another an Andy Warhol.

The curators have also displayed a small assortment of the 200 paintings and drawings of Hodler’s lover, Valentine Godé-Darel, on her death bed. One sketchbook contains the poignant hand-written note, “I’m dying, aren’t I? Tell me the truth.”

For many of his works Hodler copied Albrecht Dürer’s technique of outlining his subject viewed through a sheet of glass which is later reproduced on paper. A drawing of his portrait of Georges Navazza can be seen in the exhibition.

Military precision

Hodler took an equally practical approach to drawing military figures, using squared paper to get the correct proportions for series like the “Halberdiers”.

Many other historic scenes are on display in Geneva including sketches from the “Bataille de Naefels”, “Bataille de Morat” and “Retraite de Marignan”.

“But the real Hodler was not the artist of battles,” said Guignard.

His works, which moved from early realism to symbolism, explored nature and fundamental themes as well as the human condition: love, death, faith and hope. The characters in his pictures are always a part of something larger, linked to nature or the cosmos.

Hodler was very affected by death; he was orphaned as a young boy and all his brothers and sisters died of tuberculosis.

“He had a real need for artistic recognition. In the sketchbooks you sense this desire for aspiration,” said the curator.

“What is striking with the sketchbooks is that you are entering into his universe. He kept these books in his pockets. They were intimately linked to his life.”

Ferdinand Hodler (1853-1918) was born in a poor district of the Swiss capital, Bern. At the age of 14, having lost both parents, he started his career in an artists’ studio in Thun which produced pictures for tourists.

He then attended the Academy of Art in Geneva, a city where he spent a large part of his life.

During the years which followed, he won numerous awards for his paintings, including a gold medal at the 1900 World Fair in Paris.

Hodler was expelled from all artists’ federations in Germany after signing a petition in 1914 against the German bombing of Chartres cathedral by the German forces. His international reputation was slow to develop as a result.

He was best known for his canvases on historical and mythical themes as well as for his depictions of the countryside.

Hodler’s favourite subjects included the mountains of the Bernese Oberland, Lake Thun and Lake Geneva.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.