How Bern shaped Jean-Frédéric Schnyder’s attitude to art

Having grown up in a Bernese orphanage, artist Jean-Frédéric Schnyder is now the subject of two exhibitions in the Swiss capital. Not bad for someone whose self-declared project was not to make any project at all.

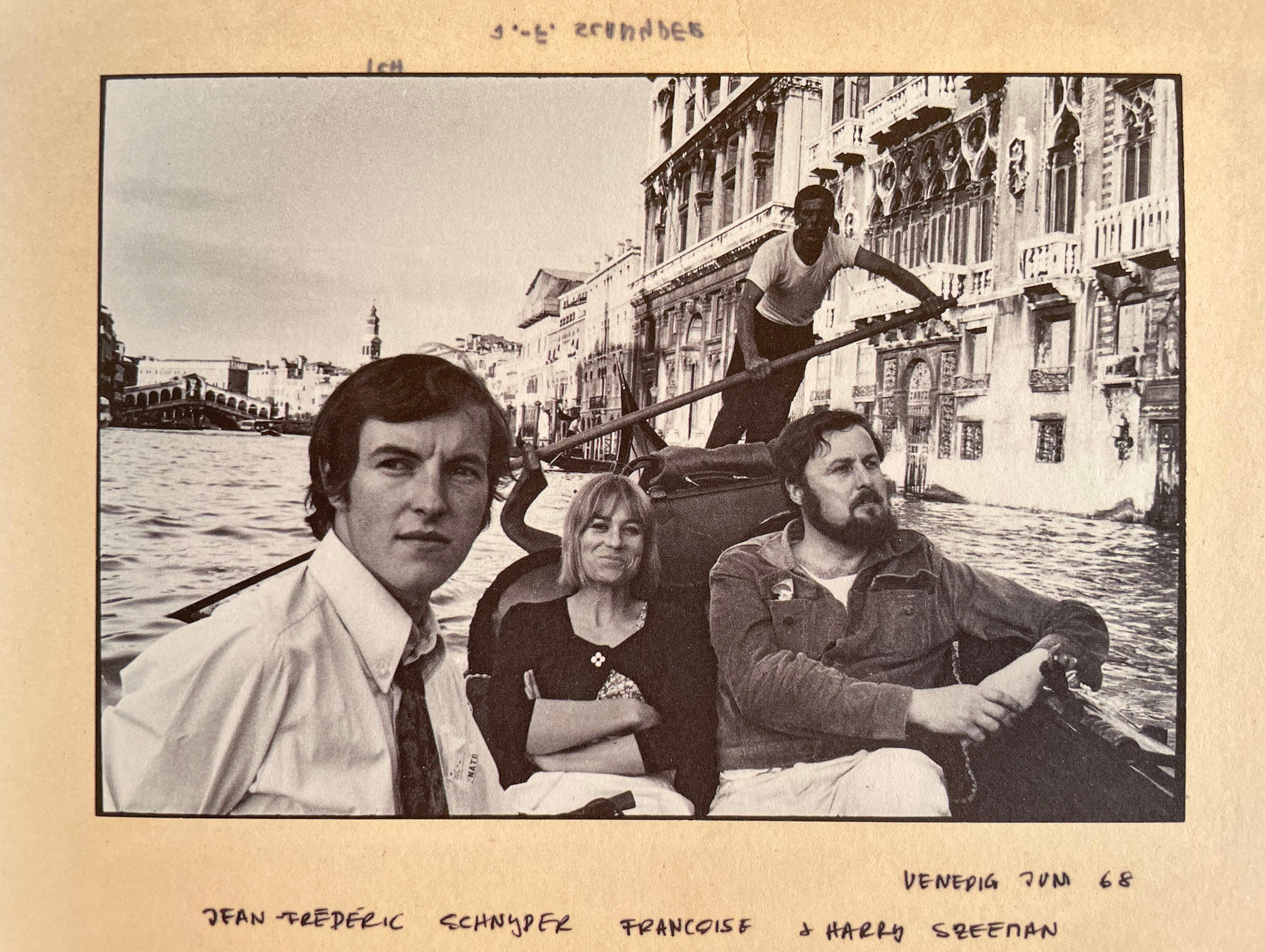

It all began in Bern. In the late 1960s the Kunsthalle (an art space without a collection) under the direction of acclaimed curator Harald Szeemann was not only in tune with the latest art trends but also attracted talent from all around the world.

Jean-Frédéric Schnyder was one of the few young Swiss artists who hung around Szeemann and who took part in the exhibition “When Attitudes become Form” in 1969. This collective experiment, a milestone in the history of conceptual art, brought together 69 artists from North America and Western Europe, including Joseph Beuys, Bruce Nauman, Eva Hesse and Lawrence Weiner among many others who would see their reputations fly high in the decades to come.

In the Kunsthalle Bern the story has now come full circle with the whole space dedicated to a retrospective of Schnyder. Now 76, he is not keen on giving interviews, but that doesn’t mean he doesn’t like to talk. During a preview tour of the exhibition he tells anecdotes about each work and cracks jokes.

“Oh, it looks so big today, when it was actually a very small circle,” he says, when asked about the importance of the late 1960s. “But it’s true that back then the big world was really present here in Bern – and we thought it was the centre of the world.”

The madness didn’t last long. Locals and the authorities were scandalised both by the most radical parts of the exhibition – the American artist Michael Heizer literally destroyed the pavement in front of the building – and by the international attention. Szeemann was “invited to resign” from the Kunsthalle a month later.

Szeemann was not just the person who “discovered” and “invested” in the young Schnyder. The lively ambience around Szeemann’s Kunsthalle certainly gave Schnyder the critical tools to develop his art on his own terms and become a “serious artist”.

Painting against the tide

Born in Basel in 1945 and raised in an orphanage, Schnyder is an autodidact who had his first contact with art via photography. His early work was mostly influenced by Pop Art and the trends displayed in the Kunsthalle exhibition: Arte Povera and so-called post-minimalism.

But when the creative bubble of Bern blew away, he felt it was time to shift gears. At the end of the 1960s he decided to learn how to draw and paint. The move was considered even more radical than the art he had been doing in Szeemann’s orbit – in 1970 painting and drawing were no longer crafts necessary for an artist. On the contrary.

Happenings, installations, concepts and performances strove to free art from the frames and splash it over all possible surfaces, material and immaterial. Painting was seen as not only politically dead, but also an outdated, bourgeois art form.

Kitsch joke?

Shortly before the opening of the exhibition in the Kunsthalle Bern, the Bern Museum of Fine Arts (Kunstmuseum) also dedicated a whole room to a rather more modest Schnyder retrospective with works from the museum’s collection.

In addition to an impressive selection of sculptures that could fit perfectly in a surrealist show, the Kunstmuseum is displaying a few works from the late 1960s and How to Paint (1973), a series of paintings Schnyder made with his wife, Margret Rufener. The title refers to Walter T. Foster’s teach-yourself art books, extremely popular from the 1950s to the 1970s.

It is interesting to note the critical reaction to this series, initially taken as a joke and often described as kitsch. Schnyder contests both categorisations vehemently.

“You have to understand that our intention with this series was not simply an experiment,” Rufener told SWI swissinfo.ch. “And it was no joke, either. Schnyder was really in love with his subjects.”

For his part, Schnyder says: “Irony is too tedious for me, and a painting is a lot of work. I cannot commit myself to a half-baked thought; you have to have some joy in your work.”

Low profile

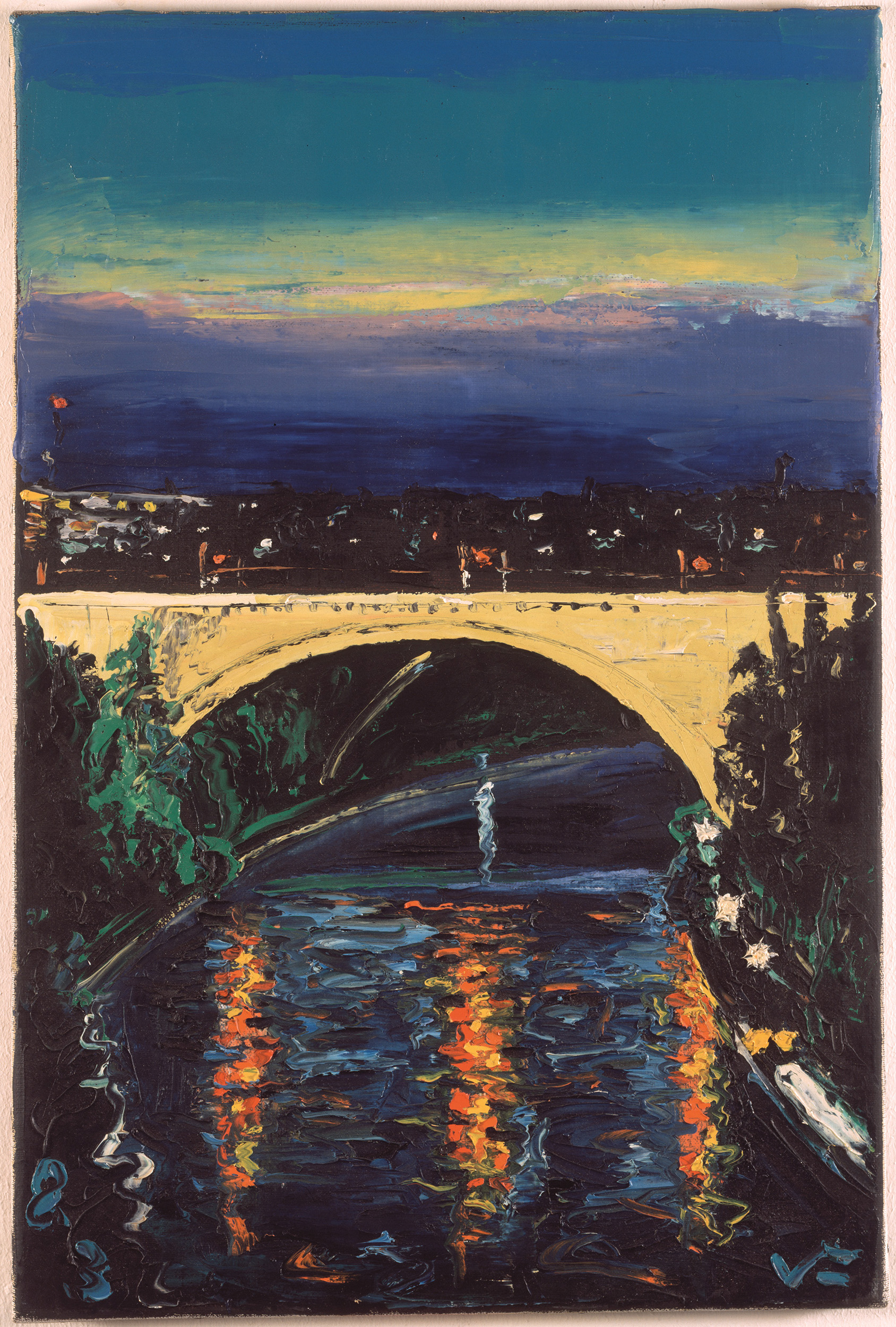

Painting became Schnyder’s preferred form. In the 1980s and 1990s he set himself up as an itinerant painter, creating series in which he explored the banal, looking for the simplest forms of beauty.

Berner Veduten (Bern vedute), Wartsäle (waiting rooms), Bänkli (little benches) and the sunsets over Lake Zug follow similar modes of production, in which Schnyder travels by bicycle or train to ordinary locations, meeting ordinary people, painting ordinary works that, all put together, make him feel closer to the extraordinary beauty of “real life”.

On the tour of the Kunsthalle he explains how he used to paint on motorway bridges. Patrolling policemen would look at his pictures and express their pleasure, truck drivers would often greet him as truckers do, lifting one finger from the wheel. He would greet them back, “just raising my paintbrush slightly over the painting”.

Despite this low-profile attitude, Schnyder didn’t turn his back on the art circuit or the art market. In addition to two participations in the prestigious Documenta, which takes place every five years in Kassel, Germany, he represented Switzerland in the 1993 Venice Biennale and had his work exhibited all over Europe and the United States. In the art market he is cared for by a highly influential gallery, Eva Presenhuber, in Zurich and New York.

Stick to the basics

The size and scope of his work varies radically depending on the material that falls into his hands, be it waste, wood or Lego pieces. “For Schnyder, stylistic pluralism is not a programme but the result of rigorous practice,” says Swiss critic Hans Rudolf Reust.

However, Schnyder insists that all he does is stick to the basic crafts of painting, drawing and sculpture, canvases big and small, miniatures.

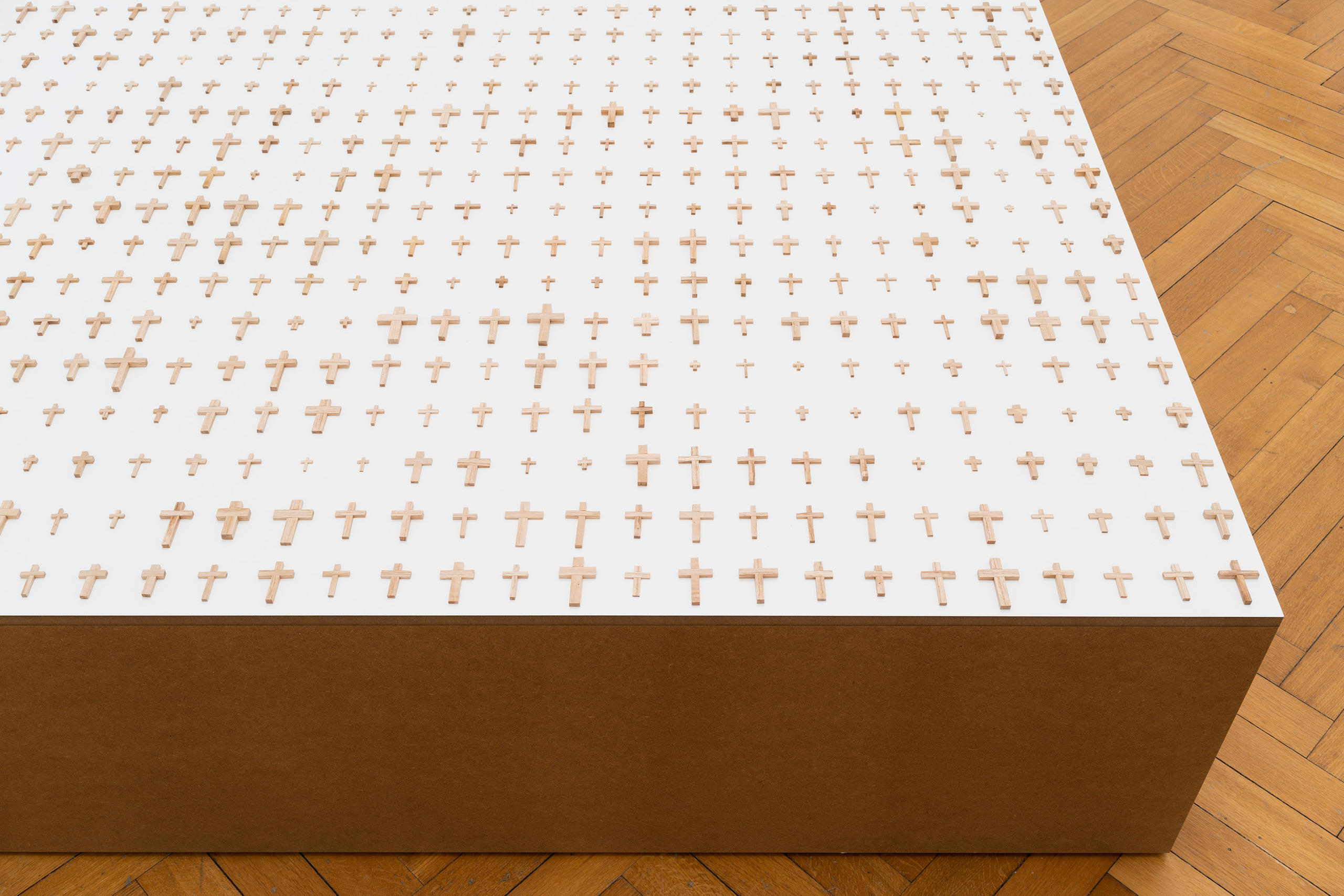

The Kunsthalle is also exhibiting some woodwork – “carpenter’s stuff” as Schnyder put it – and carvings. Prominently displayed are 9,000 of 14,000 or so wooden crosses he carved and stuck together with bone glue. On another wall, the carving knives used are strung on a string, like a chain.

Why crosses? “It’s just the simplest shape you can make out of two pieces of wood. There’s no esotericism in it. Anyone can see what he or she wants to see in it,” he says. Bone glue on the saviour’s cross, disposed as an enormous cemetery in miniature, and no symbolism at all? That’s a hard sell.

There is something quintessentially Swiss in this reserve and seemingly anti-intellectualism. Schnyder’s stance is certainly down-to-earth, faithful to the ordinary order of things, but it’s exactly this seriousness that turns a joke, or a mocking piece, into a riddle. Take it as you like, for Schnyder will not solve the puzzle for you.

The exhibition in the Kunstmuseum BernExternal link runs until May 29.

The exhibition in the Kunsthalle BernExternal link runs until May 15.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!