How Giacometti’s art walks like an Egyptian

Alberto Giacometti, the leading Swiss artist and sculptor of the 20th century, has a previously little known side – he was obsessed with ancient Egyptian art.

A new exhibition at Zurich’s Kunsthaus fine arts museum sets Giacometti’s modern works against the backdrop of relics from ancient Egypt. The similarities are striking.

Giacometti (1901-1966) is most famous for his sculptures of slender, elongated figures, including his “walking men”.

His work is highly prized – his Grande femme debout II (Tall woman standing II) sold for $27.5 million (SFr29 million) in New York in May last year, confirming him as the most expensive Swiss artist.

Giacometti’s use of the “Egyptian style”, however, is little known and it has taken a collaboration between art – the Kunsthaus – and Egyptology – the Egyptian Museum in Berlin – to bring it to life.

The result is the “Giacometti – of Egypt” exhibition, which is being shown for the first time in Zurich after its debut in Berlin.

“Giacometti all his life long was fascinated by ancient Egypt and from his youth to his last days he studied Egyptian art in publications and in the Louvre in Paris,” Dietrich Wildung, an eminent German Egyptologist and head of the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, told swissinfo.

“He produced hundreds of drawings of Egyptian sculptures. It was an obsession for him.”

Akhenaton’s features

Giacometti was still a student when archaeologists from Berlin excavated the sensational treasures of the Pharaoh Akhenaton in the early 20th century.

“One of his portraits is stylised like the Pharaoh Akhenaton,” said Christian Klemm, an art historian and curator of the Zurich exhibition.

It is placed next to a bust of Akhenaton in the exhibition and both show gaunt, elongated features.

Giacometti’s sketches of Egyptian pieces litter one room of the display, as do well-thumbed copies of early guides to the ancient civilisation’s art.

Block sculptures that had fascinated him in Florence in 1920 – where he saw Egyptian items for the very first time – are replicated as well, albeit in a more abstract form in his “Cube” sculpture.

Later on Giacometti turned his attention to motion, believing that this was the essence of life. In ancient Egyptian art, this was represented in the striding figure.

This served as a template for the artist, right down to the statue’s rectangular plinth, although Giacometti’s figures are razor thin compared with the originals.

Humanity

Klemm says that Giacometti’s intention was to “grasp the eternal dimension of humanity”. His art may have eventually looked different to that of Egypt, he adds, but the idea behind it was “still present inside”.

For Giacometti, ancient Egyptian art was, despite its strong stylisation, the most natural for showing “the tension of life”, he added.

“This is a very central point as to why he was fascinated by Egyptian things,” Klemm told swissinfo.

The curator is hoping that the exhibition, which features 20 Egyptian items and more than 80 works by Giacometti, will give people new perspectives on both types of art.

Wildung said that this already happened in Berlin, where, to people’s surprise, he dotted Giacometti around the museum’s famous collection – without flagging it up.

“Some people think that to be interested in antiquity is not compatible with an interest in modern art – not at all, art is timeless,” said Wildung, who has been a fan of Giacometti since his student days.

Ancient modernity

“We have a huge work by a contemporary artist at the façade of our museum which states on it that all art has been contemporary. Here in this Zurich exhibition our masterpieces from the Egyptian Museum in Berlin look so modern they almost look like Giacometti pieces,” he added.

Several of the museum’s most famous items are on display, taking advantage of the fact that it is currently closed for renovation.

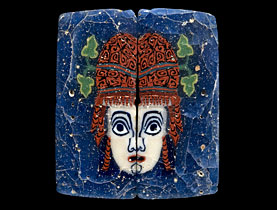

This includes a bust of the legendarily beautiful Queen Nefertiti and the Berlin Green Head. They are set next to modern Giacometti busts.

“It’s difficult to remember that these Berlin items are 3-4,000 yrs old. If you look at Green Head without knowing it comes from Egypt, many art lovers and connoisseurs would date it to the 19thcentury, that’s AD and not BC,” Wilding said.

For Klemm Egypt, along with the French impressionist painter Cézanne, remains one of the two foremost influences on Giacometti.

And proof that the great Swiss artist breathed Egyptian art to the last can be seen in a simple jotting in the margin of one of his reference tomes on the subject.

Made shortly before he died in 1966, it reads, “I’m healthy, I’m still working.”

swissinfo, Isobel Leybold-Johnson in Zurich

The display runs until May 24, 2009 at the Kunsthaus in Zurich.

It exhibits pieces from the Egyptian Museum in Berlin with sculptures, paintings and drawings by Alberto Giacometti.

The ancient Egyptian artefacts were on show until mid February in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, along with 12 sculptures from Giacometti. This museum will reopen on October 16, 2009.

Alberto Giacometti was born in Borgonovo, southern Switzerland, in 1901. He began to draw and sculpt at a very young age, later studying art in Geneva and Paris.

He came into contact with the major artists and intellectuals of the period, experimenting with Cubism, Surrealism and by the mid-1930s had rekindled an interest in drawing the human figure.

Giacometti continued to hone his craft from 1937-47, with some of his sculptures reducing in size to the point that he could carry them in matchboxes. Figures from this period, such as Walking Man, are probably Giacometti’s best-known works. They later regained a sense of volume.

He became increasingly well known in the mid-1950s in Europe and the US, but still he continued to live and work in Paris. In the early 1960s, his health began to suffer. He died in January 1966 and was buried at the village of his birth.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.