How propaganda flooded Switzerland during WWI

The gaping cultural divide between German-speaking Switzerland and the rest of the country during the First World War was exploited by internal and external propaganda on a level never seen before.

Greek dramatist Aeschylus noted that truth was the first casualty of war almost 2,500 years ago. Nevertheless, efforts to influence public opinion reached new dimensions in 1914, with little Switzerland, a neutral island among warring nations, turning into a media battlefield.

For example, in an effort to prevent the country from disintegrating, William Tell frequently appeared on posters, rising above the squabbling and symbolically evoking a sense of national unity.

“Maybe at first this interest in Switzerland can appear quite absurd,” admits Alexandre Elsig, co-curator of an exhibition “In the fire of propaganda: Switzerland and the First World War”External link, the first joint production between the Museum for Communication in Bern and the Swiss National Library.

“But we have to remember that it was the first total war with mass media and international public opinion was really important. For the Allied and Central Powers it was not only about mobilising armies but also about mobilising minds, and the neutral countries were really important in this respect, especially Switzerland which was at the moral centre of the conflict.”

Switzerland was not the only neutral country in Europe during the First World War – others included Spain, Belgium, Norway, Sweden and Denmark – but its unique linguistic set-up and central location made it a perfect “experimental lab”, in the words of the exhibition’s other co-curator, Peter Erismann.

From newspapers, news dispatches, posters and leaflets to cinema films, children’s games and advertising, both sides used all the available tools to convince neutrals of the legitimacy of their actions and to get them on their side.

“Here, for the first time, people could try out highly covert propaganda and the secret exertion of influence,” he told swissinfo.ch.

Tensions

Tensions between Switzerland’s linguistic regions had been festering since the beginning of the 20th century, with the French- and Italian-speakers feeling increasingly distant from the German-speaking majority, who looked admiringly towards their powerful German neighbour.

The “belligerents” – notably Germany and France – were aware of this internal conflict and used it to wage a propaganda war within Switzerland on a scale that had never been seen before.

Italian-speaking Swiss ended up taking a similar stance to their French-speaking compatriots. “Italy entered the war in May 1915 on the side of the Allies – which was a surprise – and as a result Ticino took a more Germany-critical attitude, which can be seen in newspaper articles and satirical magazines such as Il Ragno [The Spider],” Erismann said.

Elsig points out that Swiss people got most of their information through newspapers. “That was the most direct source. You also had illustrated magazines and news reels that were shown in cinemas before films, but mostly it was written information.”

At the start of the war, Swiss newspapers relied to a large extent on foreign news agencies, themselves controlled by government censors. As the conflict continued, the warring nations shifted to a more subtle strategy: buying controlling stakes in Swiss newspapers and “guiding” the output from within.

The result was that events were perceived and reported differently depending on which side of the Swiss “cultural divide” you bought your paper.

For example, when German soldiers burnt down the famous library in Leuven on August 25, 1914, as part of their attempts to destroy the Belgian city, the Tribune de Genève accused them of “barbarism”, whereas the Zürcher Post referred to the “alleged” destruction of Leuven. The German-language press in general tried to justify the attack by pointing to an uprising of Belgian “guerrillas”.

Later, the Schaffhauser Zeitung described France and Britain as “traitors of Europe … traitors of the white race … desecrators of Christianity”. The contempt was just as strong in western Switzerland.

Worth 1,000 words

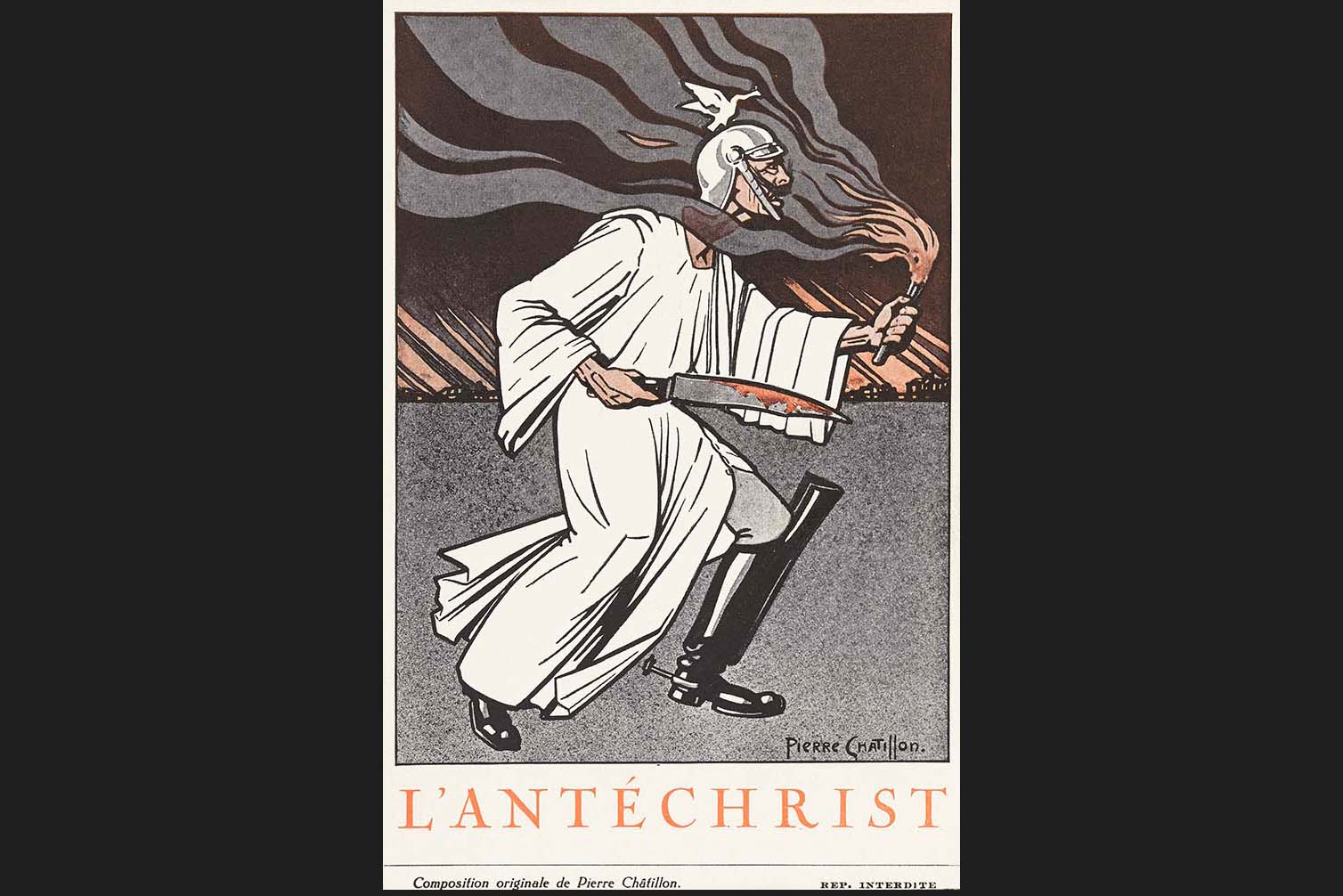

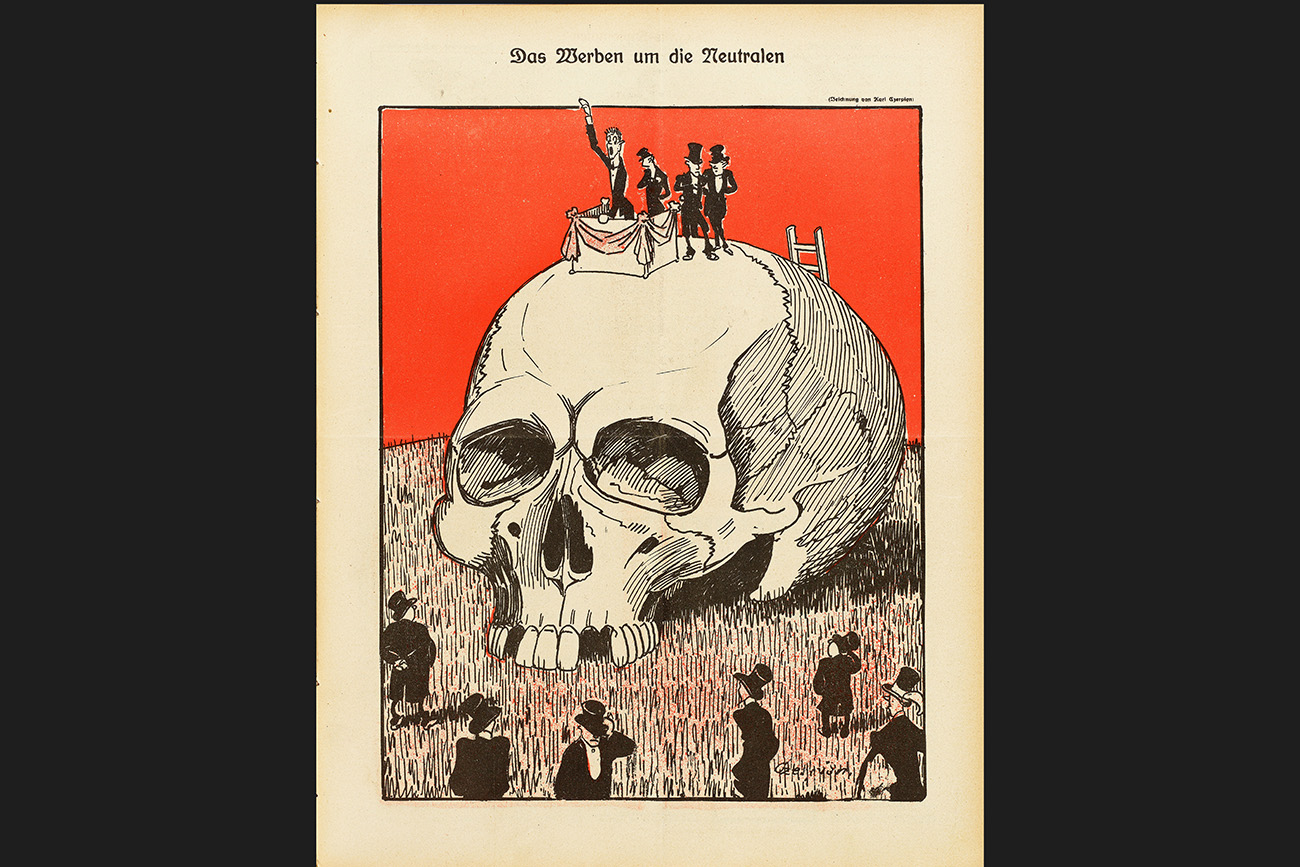

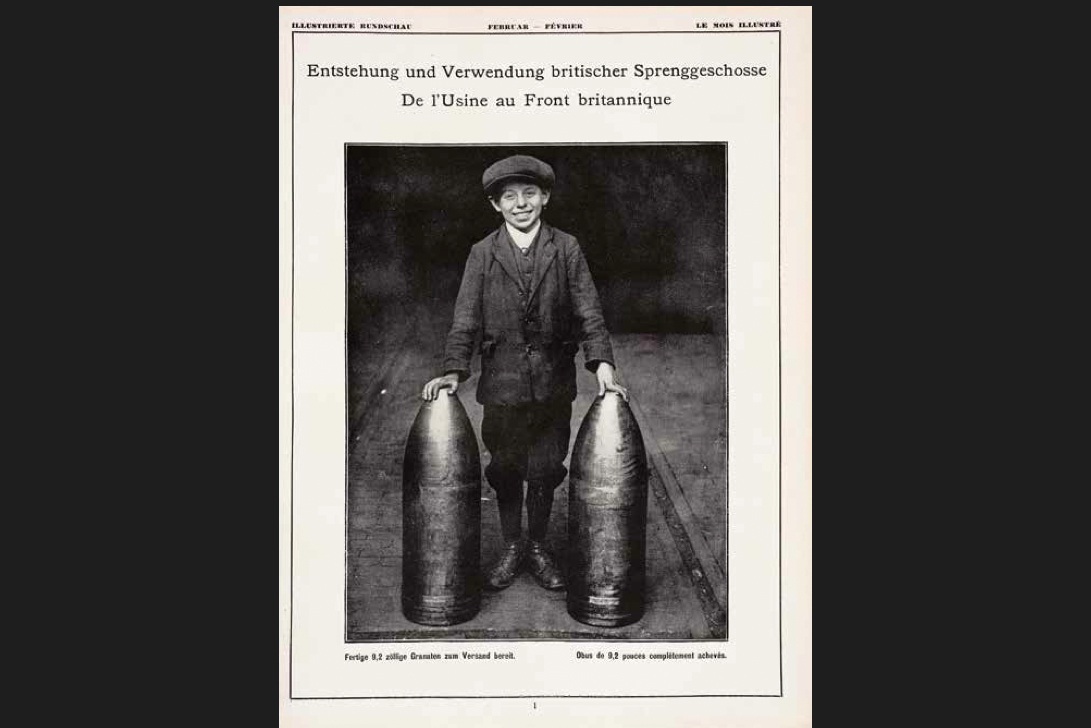

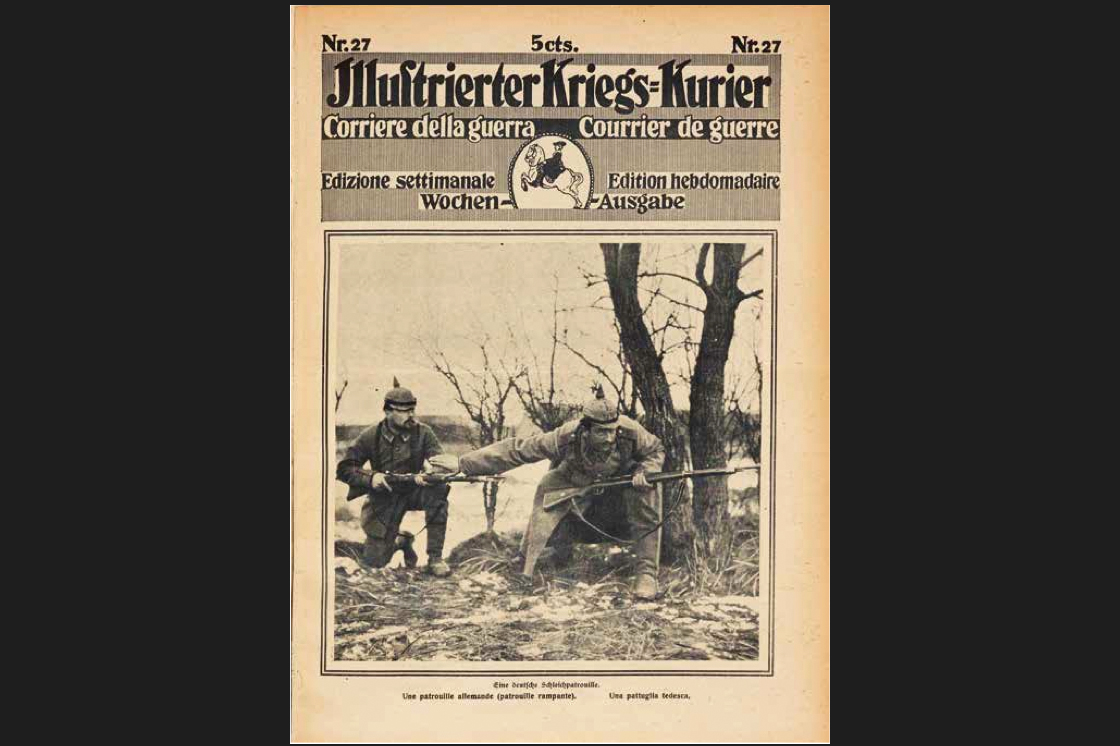

It wasn’t all newspapers, however. Since the end of the 19th century new technology had enabled publishers to disseminate images in previously unseen numbers. During the war, magazines really became a mass medium, with war pictures in particular demand.

Photographs were perceived as being faithful reproductions of the reality of war. Unlike texts, which tried to sway readers with arguments, pictures were considered to be objective. This was obviously far from the case (see gallery).

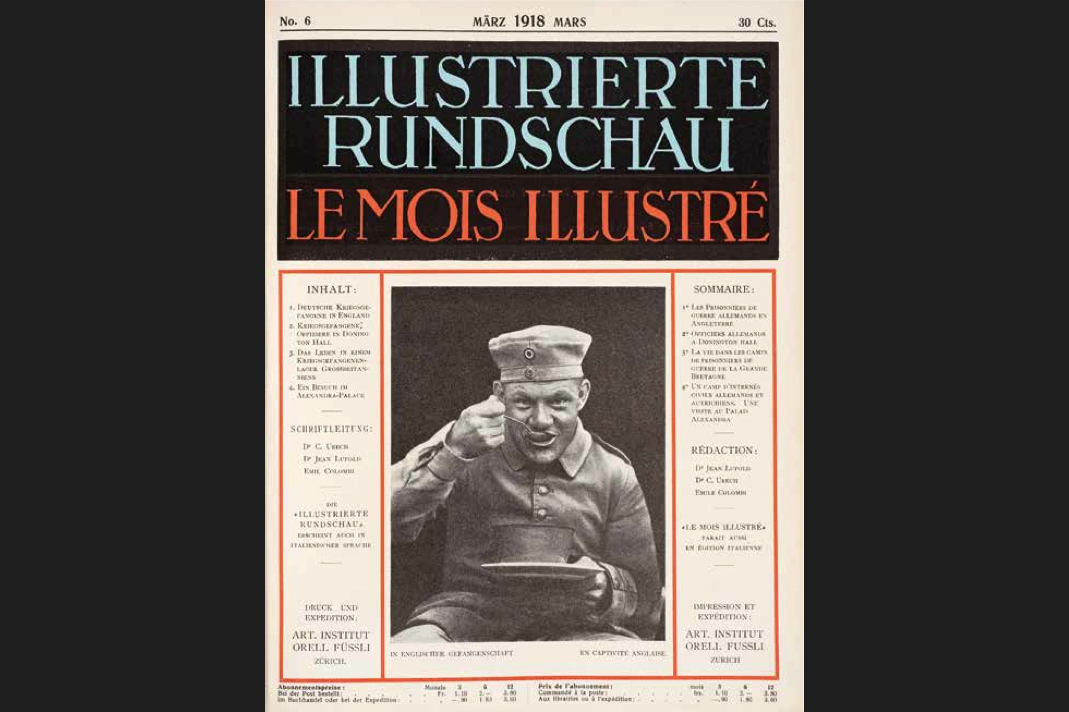

Germany moved in first with the Illustrierter Kriegs-Kurier, which had photos – many of them staged – and etchings in multiple languages. France responded by launching Mars in Basel. Britain got in on the act with the Illustrierte Rundschau, launched in Zurich in 1917.

Cultural propaganda

In 1916, as massacres were taking place at Verdun and the Somme, the warring nations developed new a tactic to win over neutral states: cultural propaganda. The aim was not only to convince the Swiss public that what they were doing was justified, but also to inspire them and win them over.

Hence the war reached theatre and cabaret stages and museums, with big names such as Richard Strauss, the Comédie-Française and the Vienna Philharmonic all performing in Switzerland. Exhibitions featuring paintings by Degas and Cézanne were also held.

Not to forget film: soon after war broke out, weekly news bulletins were shown in cinemas across the country – although, as with other media, the content was very different depending on where you were.

By 1917, the Central Powers controlled most cinemas in German-speaking Switzerland and the Allied Powers did the same in western Switzerland. This spurred the Swiss government into action and in 1917 a 50-minute documentary, Die Schweizer Armee (The Swiss Army), showing Swiss soldiers busily marching up and down the country’s borders and generally looking prepared, was released to great success. This film, the first made by the Swiss authorities, is shown in the Bern exhibition.

Postcards

And then there were postcards, one of the most popular means for spreading propaganda. Postcards were enjoying their golden age as a means of communication, with the Swiss post office dealing with 60-80 million a year between 1914 and 1918.

“They were a really common way of communicating – they were like text messages today, used for saying not much more than ‘hello, I’m here, how are you’ and so on,” Elsig said. “It’s interesting because only a few times does the text refer to the image on the postcard.”

Nevertheless, cards with powerful images – such as the damaged Reims Cathedral (see gallery) – were sent en masse by the Allied Powers to neutral countries as irrefutable evidence of German barbarism.

Since the beginning of the conflict the Swiss authorities had tried to control postcards, but the sheer amount meant they had limited success.

Even children weren’t spared the propaganda: they were used to spread the message of a heroic war and to play down the suffering of those fighting.

Herbert Rikli from Bern published a book in Stuttgart, Hurra! Ein Kriegs-BilderbuchExternal link (Hurray! A war picture book) about a child who dreams he is fighting in the war (for the Germans) like his father.

On the other side, Charlotte Schaller-Mouillot from Fribourg wrote Histoire d’un brave petit soldatExternal link (Story of a brave little soldier), which also infantilised the conflict. The Gazette de Lausanne recommended the “by turns valiant, sad and amusing adventure”.

So who won the propaganda war in Switzerland? “The winner was the one who won militarily – you cannot hide a defeat, that’s not possible,” Elsig said.

“But during the war it was harder for the Germans. They invaded Belgium and it was really hard to make this fact disappear because Switzerland was also neutral and [the invasion] was against the international rules of war.”

The exhibition

“In the fire of propaganda: Switzerland and the First World War” is the first joint production between Bern’s Museum for Communication and the Swiss National Library, is in German and French and runs until November 9.

It focuses on the propaganda war and the splits that divided Switzerland during the First World War.

The 200 or so exhibits all come, with only a few exceptions, from the collections of both institutions. Almost all are originals and include newspapers and magazines, posters and postcards, photographs and graphics, leaflets and dispatches, manuscripts, books and films.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.