How to cross the border between South and North Korea? Via Switzerland!

An exhibition of South and North Korean art from Swiss collector Uli Sigg is being shown at Bern’s Kunstmuseum (KMB) in conjunction with a documentary film made inside North Korea screened at the Swiss Alpine Museum a few blocks away. North Korea's Socialist Realism is the star of the show.

The Korean war (1950-1953) never formally ended. After an armistice was signed, South and North Korea were divided along the 38° parallel. Now, 70 years later, the two countries that once shared the same language, traditions – and a Japanese colonial past – have developed into radical different and opposing worlds. South Korea is today one of the most digitised and globalised societies while North Korea (DPRK) is arguably the most closed country in the planet.

The title of the new exhibition, “Border Crossings”, reflects the fact that the Korean border is a prohibited zone for Korean citizens from both sides. Crossing this border means making a long detour, usually via China – or, in this case, via Bern.

Kathleen Bühler, chief curator of the KMB, explains that the Uli Sigg collection and the film being shown at the same time was a coincidence. “It was pure luck. The Alpine Museum wanted to show it a year ago, but they had to postpone it because of the pandemic,” she says.

“This is such a perfect context for us because in the film we can see the people in their simple routines, how they spend their summer days in the park, and that they live their lives not much differently from us – and they also have mobile phones.”

Switzerland’s part in the recent history of the Koreas is one of those curious twists of fate. When the armistice was signed, military officers of four neutral counries took part in supervising the demilitarised zone (DMZ) dividing the two countries – Poland and Czechoslovakia on the communist side, Switzerland and Sweden on the other. The Swiss are now alone in the zone – the Alpine nation is the only country in the world recognised as neutral by North Korea. The current leader, Kim Jong-un, spent his school years in Bern.

Collector Uli Sigg is the other factor linking North Korea to Switzerland.

Sigg was an executive for the elevator company Schindler in China from the late 1970s until 1995. He became acquainted with a booming contemporary art scene when Deng Xiaoping’s China began to break its international isolation.

It was during this time, and later in the 1990s as Swiss ambassador to China, Mongolia and North Korea, that Sigg began to amass what is now the most comprehensive private collection of Chinese art in the world. Sigg’s art purchases were unquestionably one of the main impulses for the growth of artists that are now common currency on the global circuit, such as Ai Weiwei, Fang Lijun, and Xu Bing, (Sigg’s collection includes works by over 350 Chinese contemporary artists).

Sigg’s Korean collection came later in the 2000s. It is not as comprehensive as his Chinese collection. “I did not want to take on that role in South Korea; you can only do that once in a lifetime,” he explains in the Border Crossings catalogue.

Beyond aesthetics

Border Crossings was also made possible since Sigg’s artworks didn’t have to be shipped to Bern – they are stored in a Swiss castle belonging to the collector.

Considering that Sigg chose the works to be exhibited, it raises the question of the independence of the Kunstmuseum, as a public institution.

In a virtual presentation of the exhibition on April 28, Sigg, speaking from Hong KongExternal link, explained that the guiding principle of his Korean collection was not aesthetics. “It’s not a matter of taste for me. I have mainly collected works that deal with the theme of division,” he says.

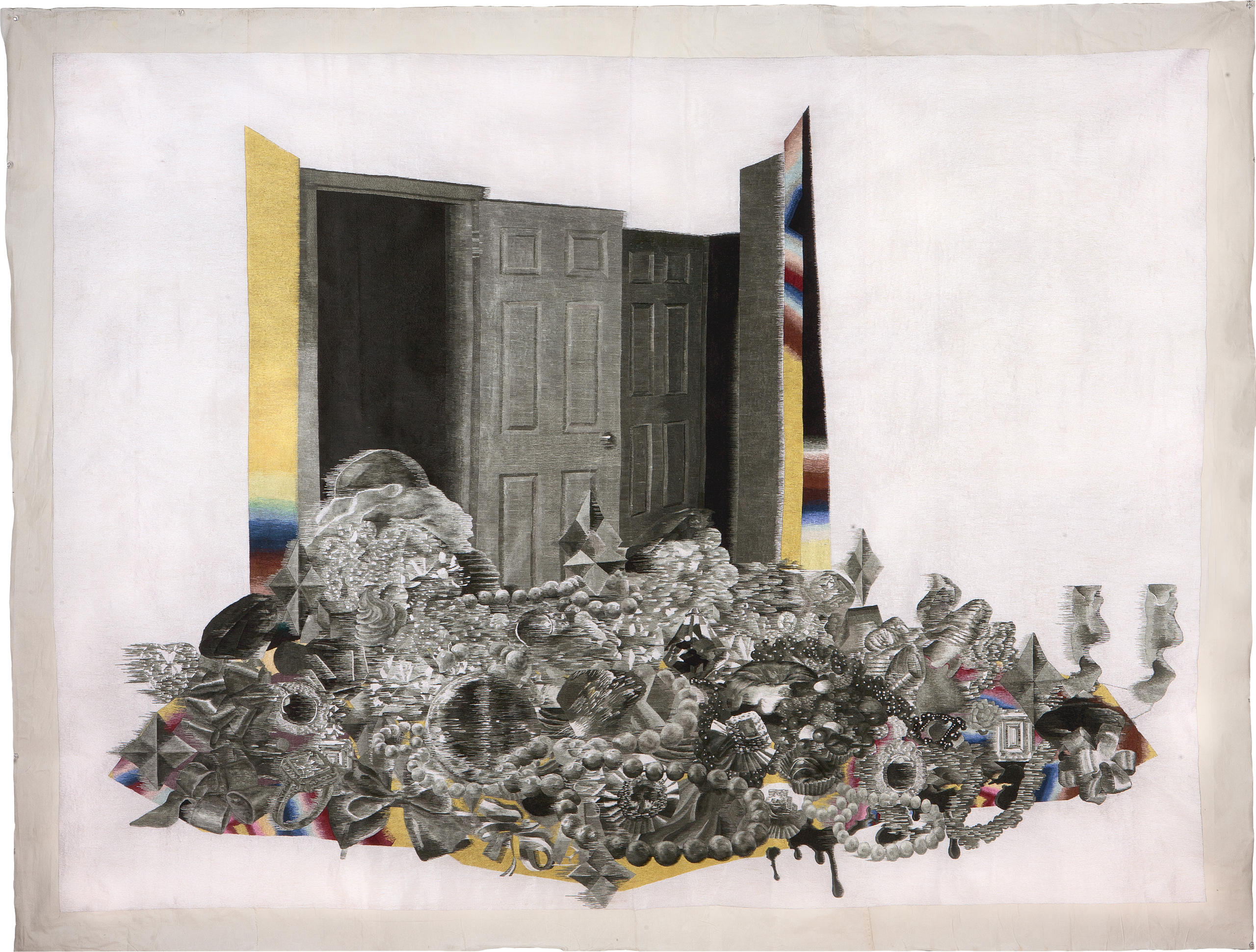

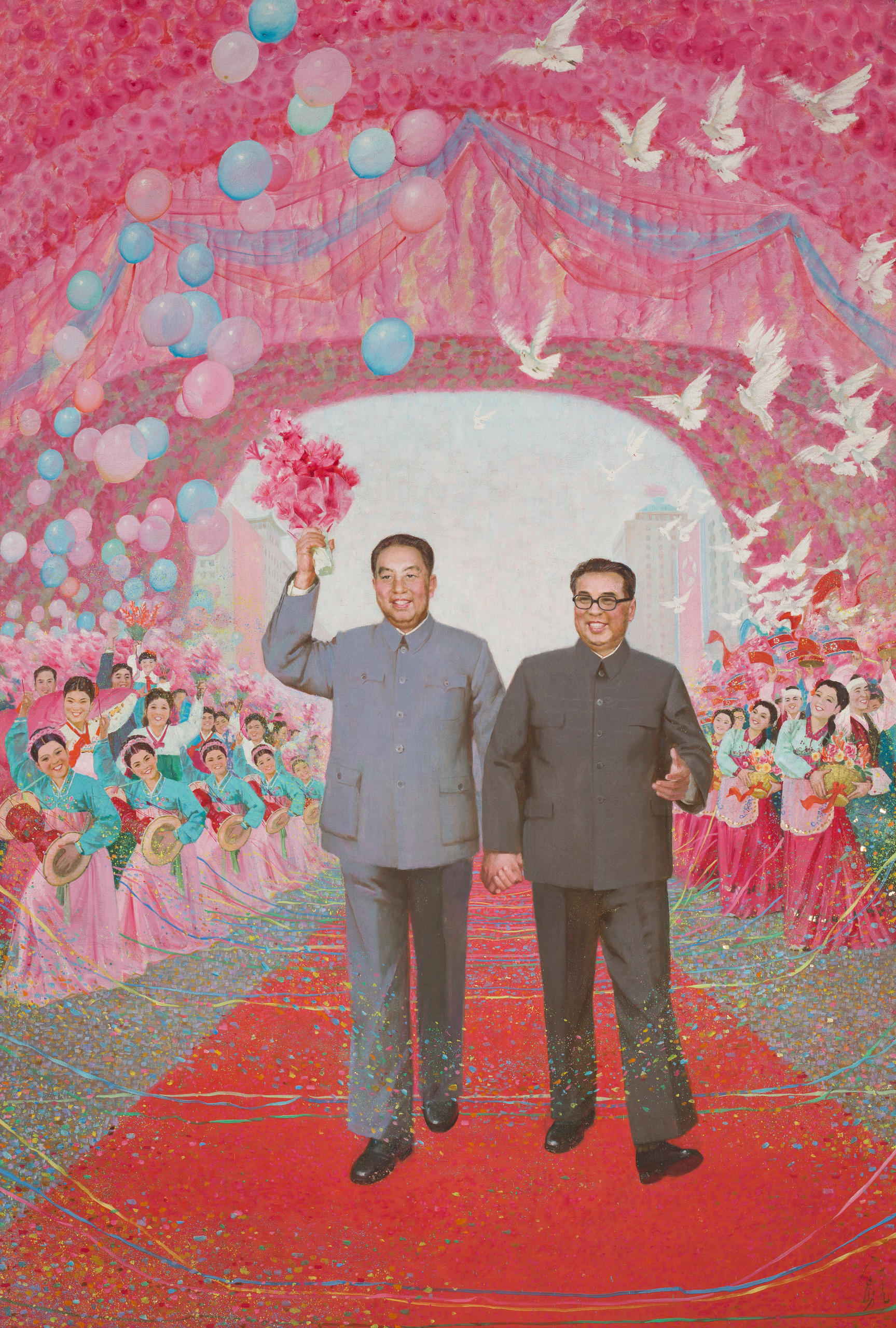

This applies clearly to the South Korean works, which provide a globalised counterpoint to the secluded North Korean artistic output, concentrated in two collective production centres: the Mansudae Art Studio and the Korea Paekho Trading Corporation. Both operate on a collaborative basis in which individual authorship is rare. Even the paintings acquired by Sigg are sanctioned copies painted by the same collective that made the originals, which are not supposed to leave the country.

The art of ‘Chosonhwa’

These impressive, huge tableaus follow a method called Chosonhwa, traditional ink-wash painting on rice paper, developed in North Korea since 1948. Its main characteristics are the vibrant use of colour, three-dimensional rendering, and expressionistic brushstrokes applied in figure paintings. The extreme emotionality depicted in these paintings may come across as quite kitsch to the Western eye, but one must consider the role that art plays not just in Korea but in the whole region.

Bühler says the deeper she dives into these diametrically opposed forms, the more it raises questions about our own Western, Eurocentric assumptions about art. “I understood something about people like Uli Sigg, as I realised that one of the impulses to collect Asian art was because in Western art we got rid of emotions. We he got rid of narrative and realism and we got rid of the expressive quality of strong, atmospheric pictures that you still find in Asian traditions,” she said.

But tradition is also an important influence in South Korean art, no matter how globalised the country may be. Part of Sigg’s interest lies in the Dansaekhwa movement that originated in the 1970s. The movement has a very strong connection to French art currents such as Art Informel or the Abstract Expressionism of the United States. Even though this was the first wave of globalised South Korean art, it was still closely tied to traditional forms, notably calligraphy.

In the case of North Korean art, it might be viewed as “pre-modern”, although Modernism, in its Western sense, is not part of the North’s dialogue. This Socialist Realist art is a development of the Soviet school. But Bühler says that the subtle ambivalence that Soviet artists tried to imbue in their works, either as a veiled form of criticism of the regime or as a way of putting their own stamp on the works, is non-existent in North Korea.

Socialism, Confucianism, and melodrama

The Korean-American critic B. G. Muhn, in an essay written originally for the Gwangju Biennale (South Korea) in 2018 – the only occasion until now that art of both Koreas were displayed together – explains the influence of what we call melodrama, and Confucianism, in Chosonhwa. He wrote: “The ostensible glorification of people’s daily lives is in part a reflection of the politics and yet it also reveals the deeper complexity of the philosophical norm of the society. The still-prevailing ideals of Confucianism dictate a desire to uphold decorum, respect and dignity in all situations. The presence of Confucianism in contemporary culture is a large source of the irony that makes North Korean art a mystery within the context of propaganda.”

Propaganda as a political tool in socialist states is not very different from how advertising works in capitalist societies. Bühler suggests we should put ourselves in the shoes of North Koreans. She says: “Imagine the impact [of these images] for the ones born there at that time and having nothing else than that.” She says that this is part of their cultural heritage and identity, and what they believe in. “The paintings can be very persuasive,” she adds.

“You also have to keep in mind that a lot of people were illiterate,” Bühler says. “This is painting for people who can’t read. It was their only source of information or access to some spiritual reality or spiritual truth, and this goes on with the Socialist Realist tradition. Think of the Catholic churches, for instance. Weren’t they also a means to convey a certain truth?”

Without a religion, North Korea is set on a fundamental ideology called Juche, commonly translated as ‘self-reliance’, but best understood, according to Muhn, “as subjecthood, or being the master of one’s own fate”. Juche can also be seen as an ideological way of covering up authoritarianism, human rights abuses and other repression.

“I do not underestimate the destructive power of the propaganda framework,” says Bühler. “But I think that exhibitions like this are always a great way of reflecting about the space we live in and the space that other people are living in right now, from very different angles, and without prejudice or bias.”

Let’s Talk about Mountains, a filmic approach to North Korea at the Swiss Alpine Museum can be seen until July 3.

Border Crossings at the Kustmuseum Bern runs until September 5.

More

A tour of the DMZ with a Swiss guard

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.