Berlinale 2024: a Swiss voice cries the despair of the Israeli left

The Swiss-French actress Irène Jacob stars in Shikun, a free adaptation of Eugène Ionescu’s 1959 play Rhinoceros, directed by the Israeli master Amos Gitai. A fable depicting the rise of fascism, it premiered last week at the Berlin Film Festival.

The Berlinale this year, now in its 74th edition, closed last Sunday (Feb. 25) convulsed by protests and political controversyExternal link.

Whereas the Palestinian-Norwegian co-production No Other Land, made by a collective of Palestinian and Jewish Israeli journalists, took the prize for best documentary – and the filmmakers’ acceptance speech has already provoked fierce backlash from German politicians — a rather muted response has welcomed Shikun (‘social housing’ in Hebrew), the only Israeli film in the main programme.

This latest work, a co-production with Switzerland, France, the UK and Brazil, is signed by the country’s foremost filmmaker, Amos Gitai, whose archives are deposited in the Cinémathèque Suisse. Shikun is his first Swiss co-production.

Political extinction

Unlike at the European Film Market the previous evening – when pro-Palestinian protesters took over the main hall and called for an end to the war and occupation – the premiere of Shikun was not met with much protest.

According to the Jerusalem PostExternal link, the Q&A at the Haus der Berliner Festspiele reportedly featured one call for a ceasefire and a question, directed at the German Minister for Culture Claudia Roth and Gitai himself, about whether Germany should sever diplomatic ties with Israel over “its ongoing genocide”.

Perhaps in part this is because the film itself is a desperate cry of protest from an author who has, during his extensive career, been identified as one of the most vocal representatives of the Israeli so-called “peace camp”, another kind of endangered species.

This shrinking political force, mainly associated with the Israeli left but not exclusive to it, has, like Gitai himself, seen its efforts to defend Palestinian rights and to criticise Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian territories come to very little.

Watch here a recent interview of Amos Gitai for the news channel France 24, right after the Hamas attack of October 7th:

The rhinos among us

This latest work is a free adaptation of the 1959 play Rhinoceros by Eugène Ionesco, in which the population of a French town in the 1940s turns towards fascism and political nihilism.

At the start of 2023, Gitai shot this updated staging in Tel Aviv and Be’er Sheva, a large Israeli city just south of the West Bank and 40km from Gaza, in response to the massive wave of protests that paralysed Israel after the coalition government’s attempt to restrict the power of the judiciary and the Supreme Court.

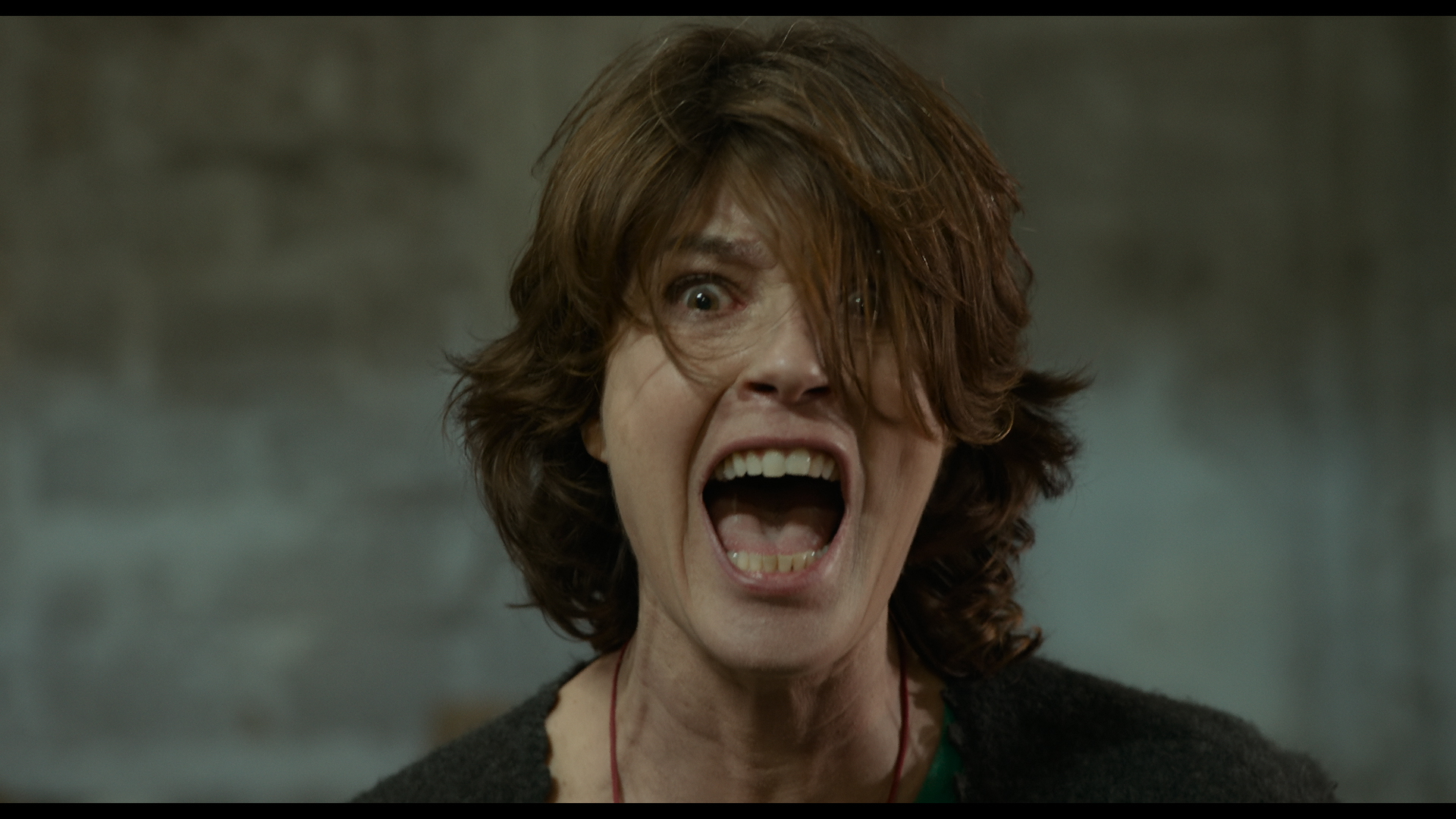

Notably, the star of the film is not Israeli but Swiss: Irène Jacob. She plays a woman – the embodiment of a mad chorus – driven to physical and mental ruin while witnessing the turn to fascism all around her.

Gitai, via Jacob, discards any subtlety to picture the desperation of the Israeli left while it watches, impotent, the rise of a nationalist, supremacist, ethnocentric, theocratic, and illiberal regime that, it fears, is already putting the lives of Jews and Muslims in peril all over the world.

“How did the fight against terrorism turn into destroying water pipes?” one man asks. “We must leave some trace,” says somebody else.

Symbolic setting

When I meet her at her hotel in Berlin, Irène Jacob is sitting on the far side of a dining room rented for the occasion, alone at a large circular table intended for dinner receptions and ceremonies.

Near the door, Amos Gitai is slumped in an armchair, tapping away at his phone. Behind Jacob, the row of wide windows that illuminate the room look out, rather surreally, onto a view of the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, near to the Brandenburg Gate and Hannah-Arendt-Strasse.

At the table, with my recorder in between us, I waver initially about characterising her as Swiss, trying to find the right words, since she was born in Paris and only later moved to Geneva to study. “Yes, I am Swiss,” she asserts, smiling. “That is what I am.”

There are other journalists in the room. “What is your opinion about the war in Gaza? Or Ukraine?” one offers.

She cuts in, politely, sensing that the question needs a sharp response: “War is just horrible. Darkness, death, destruction. I don’t think we can say something else. In this film, we could only make a social space, artistically, where you see these people altogether, carrying these stories [of war] with them.”

Inspiring corridors

Unfolding mostly in theatrical long takes, Shikun takes place in a series of semi-deserted locations across Israel: a parking garage, a Brutalist-style housing complex, the Tel Aviv bus station (deserted at night-time). The first scene takes place on a corridor in the housing project, and, like most of the film, is captured in one such bravura sequence shot.

“He was very inspired by that corridor”, says Jacob about Gitai. “We shaped the film just from our rehearsals; I would be in Paris, and I would send [Gitai] videos, monologues. We were working on a play together. Then he suggested I look at Ionesco. By the time we got to that corridor, we had all this in mind.”

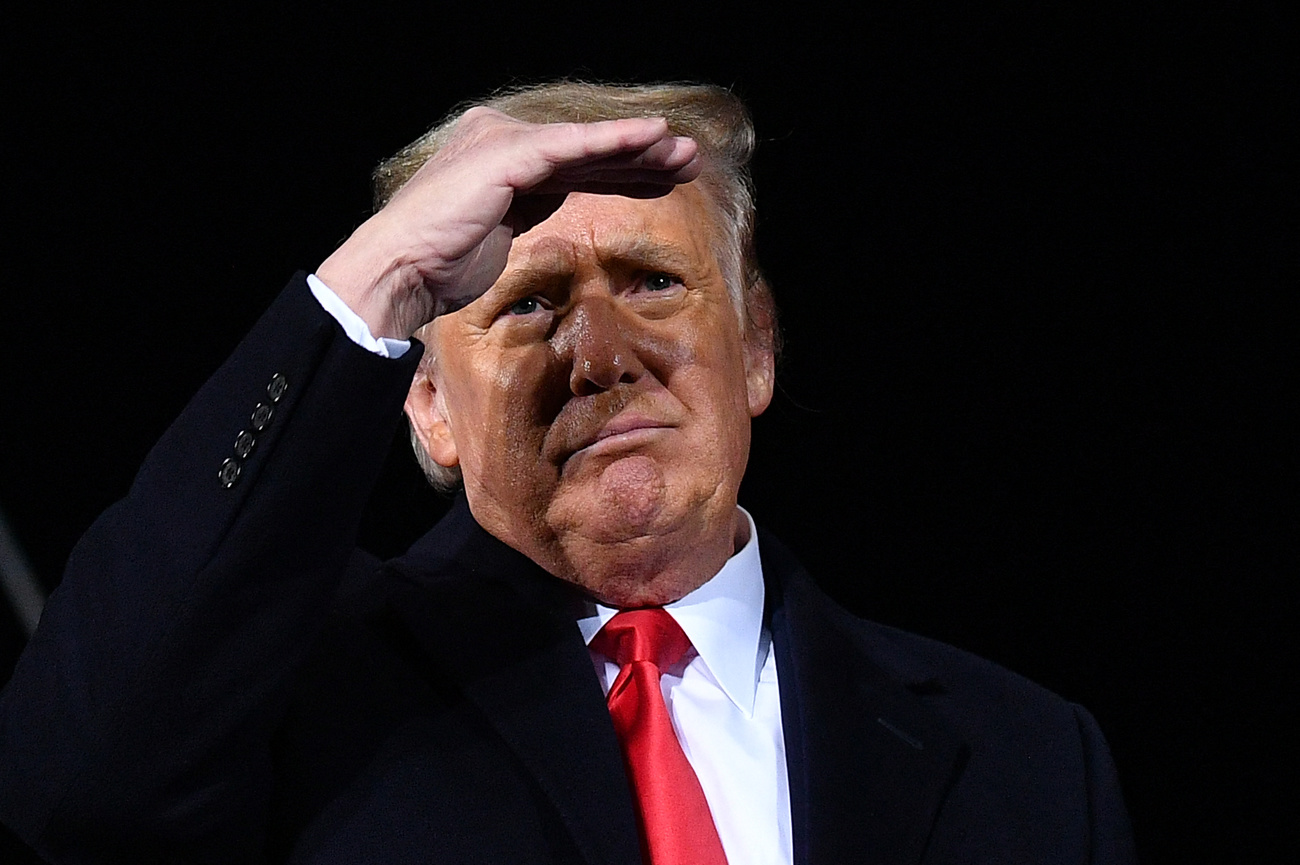

“We all had different stories to tell. We came with these prepared texts – in Hebrew, French, Ukrainian – and worked from there as a start. But once [Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s re-election] happened, there was even more of an urge for us all to make it quickly.”

Rhinos In Hebrew: follow the herd

Gitai, from the other side of the room, calls me over to speak with him too. Jacob comes and sits on the chair opposite and watches quietly as he speaks.

“During the protest movement, the Israeli press—liberal press—started to use this term, rhinoceros, inspired by Ionesco,” he says. “I met [the playwright’s] daughter in Paris and she told me the Hebrew language is the only language where rhino is both a noun and a verb, hitkarnefut. To become a rhinoceros and follow the herd. From that, I went back to the source.”

“[Irène Jacob] is intelligent, sensitive, not mundane”, he adds, gesturing to her as she looks on. “She likes the work, the intellectual challenge, the reflection. She came to Israel with a mission to work on my own play, House, which will soon go to London, Berlin, Rome. Since she was there, I took her around the country. With intelligent people, you have to stimulate them with new knowledge, so that they can give you something more precise back.”

Jacob tells me: “After rehearsals, once we were in those locations, we organised the shots in a collaborative way; it was certainly a unique experience, building the film as we went along. That was inspiring. Trying to find things on the spot, making them happen. Trying this, trying that. What can we do? Time passes in a different way with Amos. Long moments where anything can happen – and does. This gives a lot for a performer to work with.”

Multicultural illusion

Jacob mentions that she worked with a choreographer friend to coordinate her jarring physical movements in Shikun, which seem to explode out of her as the film progresses, frazzling us with their seemingly involuntary quality. I put it to her that it’s difficult, watching the film in Berlin at this time of civilian carnage, not to see that as a symptom of the death and destruction filling our screens since this war began.

“All the violence was there before. Present on an everyday basis. It is not obvious, maybe. Did I see it? No, I didn’t see it. It’s not overwhelming, right? It’s not dangerous. Or is it dangerous? You are on the verge of seeing something approaching, something that isn’t normal. Everybody should have their opinion, right? Or if you’re no longer allowed to have yours, is it okay? All this violence has been present there for quite some time.”

“Am I speaking French?” Jacob’s character in Shikun asks, as if to herself. “Nobody knows if I’m speaking French, so who cares if I speak.” All around her, the sounds of Ukrainian, Hebrew, Yiddish, Arabic. A multicultural Israel that looks, in this snapshot of time, like it could have just been an illusion, an ephemeral hope.

Edited by Mark Livingston and Eduardo Simantob

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.