James Bond: ‘It’s the double whammy of sex and violence’

From “misogynist sociopath” to “lethal comedian”, everyone has an opinion of James Bond, the British spy who this year celebrates 50 years on the silver screen. Not a few people, however, would mind the baddies finally getting their way.

“I think you’re a sexist, misogynist dinosaur, a relic of the Cold War, whose boyish charms, though wasted on me, obviously appealed to that young woman I sent out to evaluate you.”

This view of Bond came from M, Bond’s boss, in the 1995 film GoldenEye. This was not only Pierce Brosnan’s first outing as 007, but also notably the first time M had been played by a woman, Judi Dench.

Until then, women in Bond girls were rarely more than filling for bikinis, whom Bond would usually seduce and try to save.

Indeed, surviving a Bond film as a woman is an art in itself. “Don’t have sex,” advises Kimberly Neuendorf, professor of communication at Cleveland State University and author of Shaken and Stirred: A Content Analysis of Women’s Portrayals in James Bond Films (see link).

“Also, you need to be morally good by the end of the film – some characters associate with the antagonist and then switch. Don’t try to kill Bond – that’s the strongest predictor: if you try to kill Bond, you’re dead!”

Neuendorf and other researchers analysed almost 200 female characters in 20 Bond films. Key findings included a trend of more sexual activity and greater harm to females over time, but few significant differences in characteristics of Bond women.

“Societies in general, across cultures, have changed a bit over the years as to which physical characteristics of women are considered attractive. This was not reflected in the James Bond girls – they’ve remained young, slender and beautiful,” she told swissinfo.ch.

More

James Bond: half-Swiss, totally profitable

“Well-established brand”

The insight that James Bond films are formulaic is hardly new: in 1979, Italian essayist Umberto Eco drew up a list of nine “moves” which appear in every Bond novel (see box).

In 1979, Italian semiotician and literary critic Umberto Eco analysed the narrative structure of Ian Fleming’s Bond novels. The results are often equally applicable to the films.

Eco proposed that the characters in Bond novels are allocated specific roles or actions to perform. He wrote: “The [Bond] novel … is fixed as a sequence of ‘moves’ inspired by the code and constituted accordingly to a perfectly prearranged scheme.”

Eco lists these “moves” as:

A. M moves and gives a task to Bond.

B. Villain moves and appears to Bond (perhaps in vicarious form).

C. Bond moves and gives a first check to Villain or Villain gives first check to Bond.

D. Woman moves and shows herself.

E. Bond takes Woman (possesses her or begins her seduction).

F. Villain captures Bond (with or without Woman, or at different moments).

G. Villain tortures Bond (with or without Woman).

H. Bond beats Villain (kills him, or kills his representative or helps at their killing).

I. Bond, convalescing, enjoys Woman, whom he then loses.

According to Eco, all the moves appear in every one of Fleming’s novels, although each move may appear more than once and they do not always occur in the same sequence. Dr. No can be termed the archetypal Bond novel as Eco’s moves run ABCDEFGHI.

(Source: The Role of the Reader: Explorations in the Semiotics of Texts (1979))

Understandably, producers are reluctant to fiddle with a winning formula. Since 1962 the 22-film franchise has taken in an estimated $5 billion (CHF4.78 billion) – more than $12.5 billion when adjusted for inflation – making it the second-highest-grossing film series of all time (behind Harry Potter).

“First of all they are excellent films as entertainment. They have a well-established brand. Also, they work on the international level, which is very important,” said Jeremy Black, a professor of history at Exeter University in Britain and author of The Politics of James Bond: From Fleming’s Novels to the Big Screen.

This is not to say that the films – and particularly Ian Fleming’s novels – haven’t aged. Black highlights the chain-smoking and casual racism of the earlier adventures.

“They’re novels of their time – does [Jane Austen’s] Emma age as a novel because no one has courtship patterns of the beginning of the 19th century?” he asks.

More violent

Another change, which Black regrets, is the increasing level of violence. “They’re struggling to respond to the challenge mounted by the Jason Bourne films [first released in 2002]. Also, much of the audience is not British, and without any criticism of them, they don’t necessarily want cerebral discussion,” he said.

“You need to remember that the Bond of the novels doesn’t really like killing people, which is not exactly what you’d assume from the way it’s generally presented.”

One critic, for example, described Roger Moore’s Bond as a “lethal comedian”.

For Black, part of the strength and appeal of the Bond character is that it can be interpreted differently by different audiences. Thus for John Le Carré, master of spy fiction who studied at Bern University in Switzerland, Bond is the “ultimate prostitute”.

Matt Damon, who played Jason Bourne, isn’t a fan. In 2009, he described Bond as “an imperialist, misogynist sociopath who goes around bedding women and swilling Martinis and killing people. He’s repulsive.”

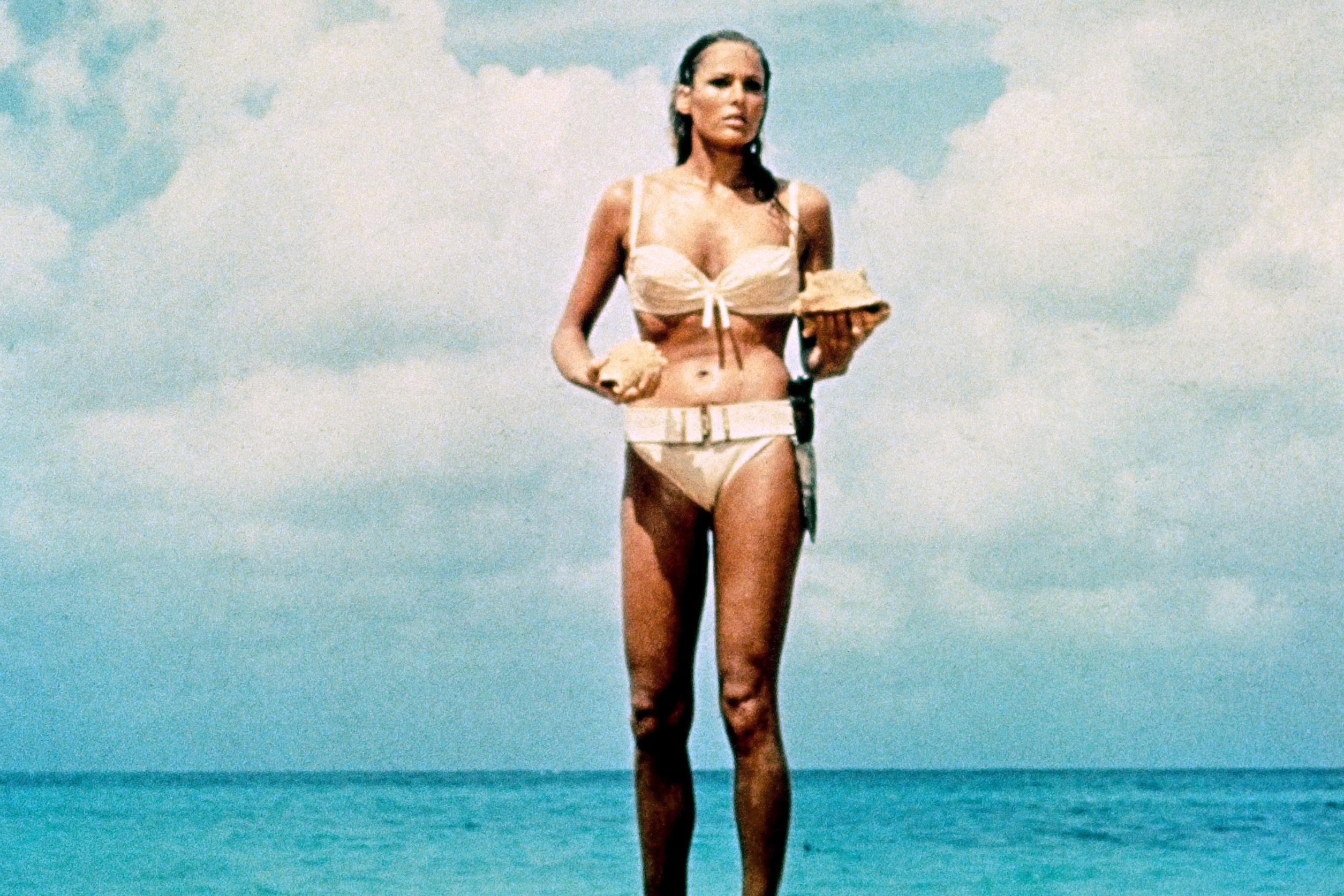

Iconic bikini

But if Bond has evolved to an extent over the past half century, so has the outside world.

When Switzerland’s Ursula Andress emerged from the sea in Dr. No in October 1962, Swiss women could run out and buy a similar bikini but they were still almost a decade from getting the vote.

“I think [the bikini] had a huge impact,” Neuendorf said. “At the time there was much talk about it, because it’s not just the clothing but also the way she wore it – the sexualisation of women. There’s a dagger with its sheath…”

More

Sashes to sashes: the death of Miss Switzerland?

Nevertheless, the link between sex and violence – who can forget the opening credits of naked women dancing around giant loaded guns? – is not without problems.

Neuendorf points to body image problems for women and a “notion of mortality”, which some cultural theorists have said seeped over from Bond into the teenager horror/slasher films of the Seventies and Eighties such as The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and A Nightmare on Elm Street.

“The notion is that characters who have sex – especially young girls – are the ones who’ll be killed by the slasher. This has chilling consequences: women are not free to have sex. If they have sex, they are punished,” she said.

“It’s the double whammy of sex and violence. The Bond films were among the first, maybe a harbinger of those trends.”

Escapism

But how seriously can one take films with female characters called Plenty O’Toole, Holly Goodhead and Pussy Galore? Austin Powers suggests not very.

Surely Bond is ultimately just a teenage boy’s dream of gadgets and girls? Nothing more than pointless fun – reassuring escapism in which the goodies always win in the end.

“The whole point about James Bond is that on his own he’s saving the world – well, that generally doesn’t happen,” Black pointed out.

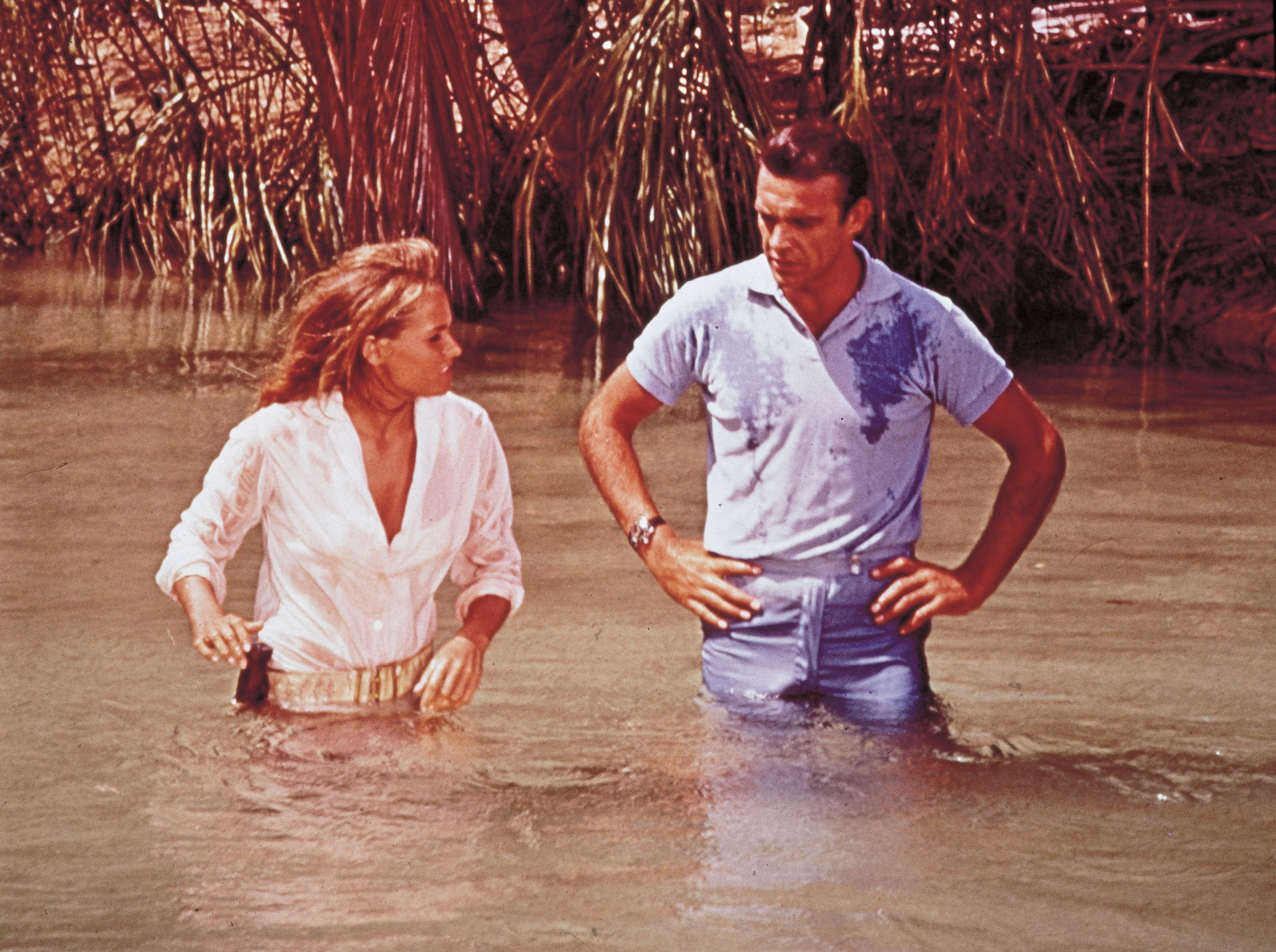

Both Black and Neuendorf pick Sean Connery as their favourite Bond, although Black says Timothy Dalton is most similar to the Bond of the novels, “a rather dark, introspective, Romantic hero”.

Neuendorf is more succinct. “It’s the twinkle in the eye!”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!