Jean Tinguely’s whimsical contraptions return to Milan for centenary showcase

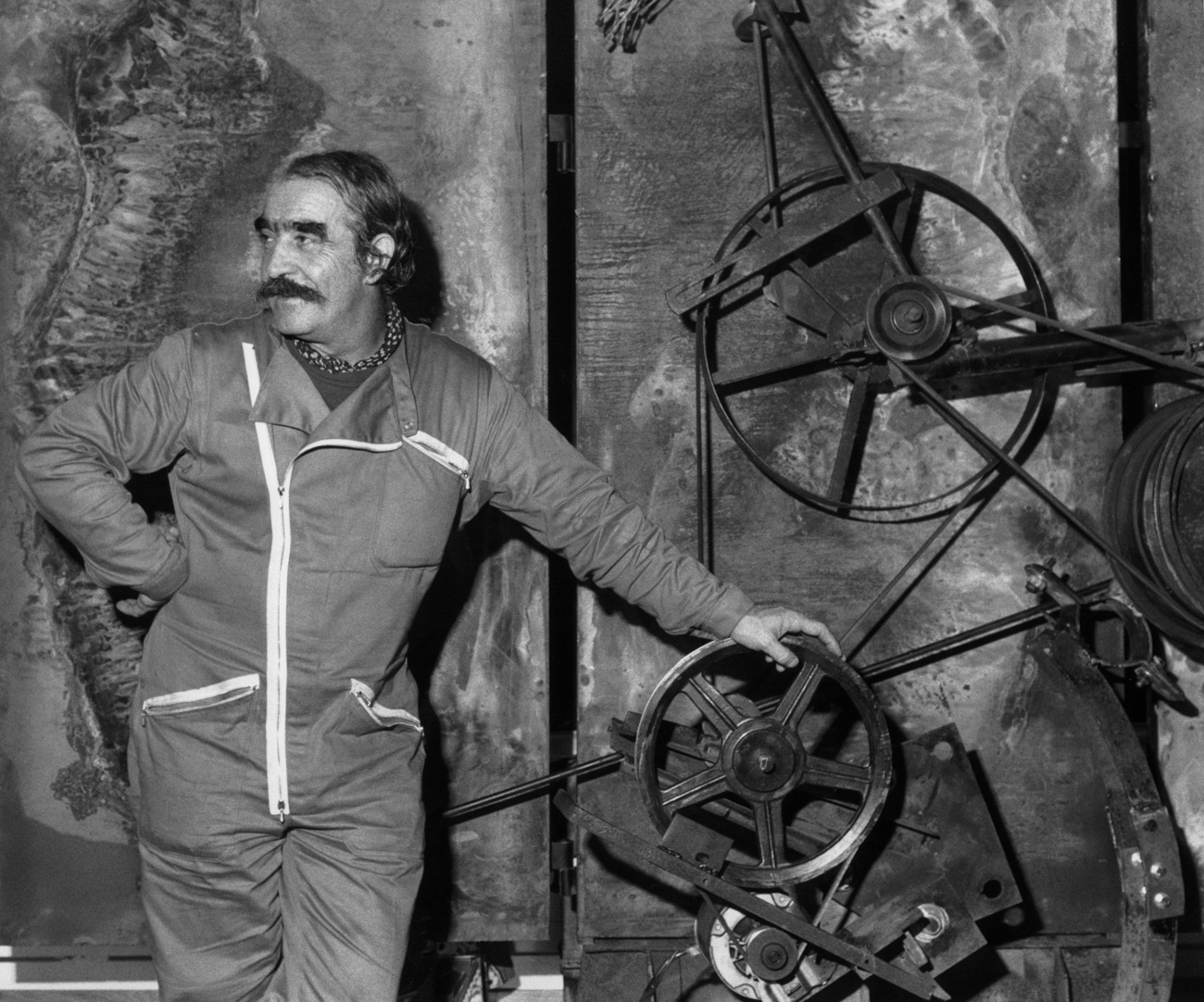

A major exhibition at the Hangar Bicocca in Milan opens the celebrations for the centenary of the birth of Jean Tinguely (1925-1991). The selection of 40 sculptures, produced between the 1950s and 1990s, validates his reputation as a pioneer of kinetic art.

Jean Tinguely was just a boy when the old Hangar Bicocca shed was a vital cog in Mussolini’s war effort, transforming cast iron into parts for locomotives, airplanes and military equipment. The foundry continued to exist until 1986, when it was converted into a cultural centre.

The exhibition in MilanExternal link represents the closing of a circle in Tinguely’s international career. Here, in 1954, the fledgling artist took part in a show at the invitation of Bruno Munari (1907-1998), one of the creators of programmed and kinetic art. Tinguely’s contribution to the show ‘Tricycle’ (1954) is part of the Milan retrospective.

It was the beginning of the post-war economic boom and consumer society was emerging. The enormous amounts of waste material from industrial production was ripe for resurrection. Tinguely saw old, abandoned iron as the raw material for his kinetic sculptures.

For him, “the machine is first and foremost the instrument that allows me to be poetic”. Trains, cars, motorbikes, bicycles, toys and household appliances were taking over the streets and homes. They were great novelties, with hidden gears packaged in well-designed boxes – all of which would end up in the bin sooner or later.

Fun and games

Tinguely observed, explored and ultimately stripped down the assembly lines. He extended the useful life of objects and endowed them with an amusing uselessness, this time dismantled and sculpted, verticalised or horizontalised, with no identification to their original purpose. Wrecks of agricultural machinery, crushers, drilling machines, pot lids and shark jaws, among many other items, have acquired new purposelessness and dysfunctions.

The artist subverted the industrial project, rearranging new forms and functions that were almost always useless and therefore had comic or tragic meanings but always provocative. Thus, as one of the pioneers of kinetic art, he became one of the leading figures in the Nouveau Réalisme movement, which favoured the use of recycled materials.

Artists who thought about recycling junk were still rare at the time. One of them, the American Richard Stankewicz (1922-1986), inspired Tinguely with his static works made from reused metals. Tinguely came across his work in 1948, and that was the spark that ignited the imagination of the artist, who had already made a small motorised object hanging from the ceiling. In honour of Stankewicz, Tinguely built and destroyed his famous Homage to New York in the MoMA garden in 1960.

“Certainly, the ephemeral element of surprise was part of the system of machinery built by Tinguely. There wasn’t much planning, everything was put together on the spot,” says Lucia Pesapane, co-curator of the retrospective, during the opening of the Milan exhibition. “And he had a lot of fun when it didn’t work out. For him, this element of improvisation and rupture in his works was a reflection of the ‘real life’ that we have to accept. The more they exploded and self-destructed, the more truth was achieved.”

Assembly secrets

Even before they trigger interpretations of the beholder, the complexity of Tinguely’s contraptions challenge those who have to assemble it. According to Pesapane, one more characteristic of the artist is revealed – nothing can be left to chance.

“The transport, assembly and disassembly of Tinguely’s works is a monumental job, thought out and carried out down to the smallest detail by the artist himself, and almost always without an instruction manual,” says Pesapane. She remembers that the 1960s weren’t like today – the logic of the market still didn’t rule the art circuit. “Tinguely was quite happy for works to be destroyed and wasn’t so concerned about their conservation and preservation. And this adds a coefficient of difficulty to the realisation of this show, which spans from the beginning of his career to the end of his life in the early 1990s,” she says.

Half of the works for the retrospective came from the Tinguely MuseumExternal link in Basel and the other from museums in Germany, France, Holland and private collections. Preparation for the exhibition took almost two years. Each work has its own box, but the monumental works have as many as ten or fifteen boxes. “The logistical complexity adds to the fascination of seeing them here,” says Pesapane.

Adult childhood

The Swiss artist’s works are permeated with curiosity and creativity, reminiscent of the world of children. On the one hand, they are playful in their essence and guiding principle. On the other, the sculptures reflect on the world that was accelerating in all areas of life. In the end, the aspect of play outweighs the engineering of the gears.

“The question of play is central to his work,” says the director of the Tinguely Museum, Roland Wetzel. “He grew up in a Catholic family environment and Basel is Protestant. I think this condition has given him a different perspective on the world.”

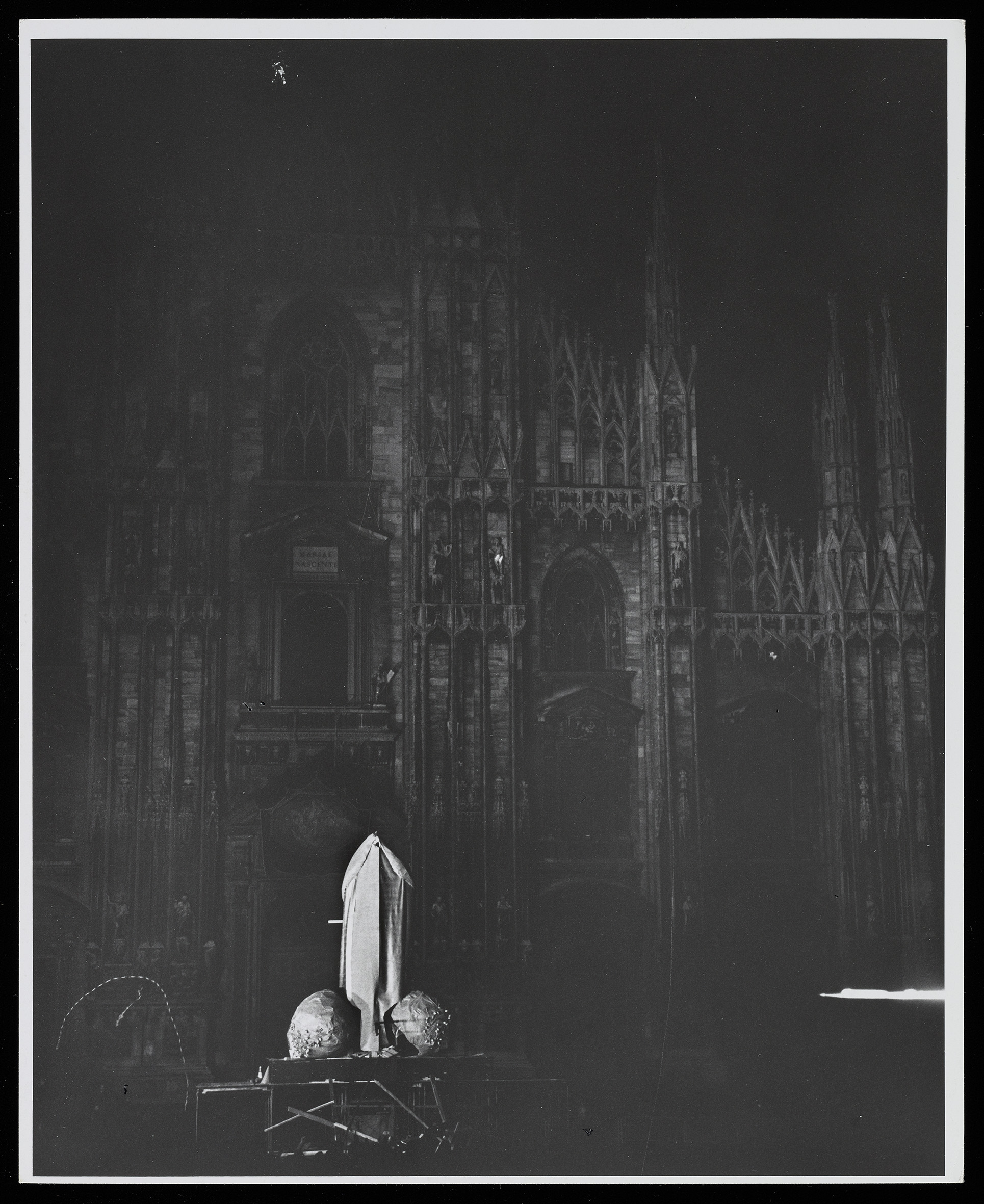

The exhibition space is proportional to Tinguely’s intellectual greatness and artistic immensity: five thousand square metres are occupied by his sculptures. An adjoining room hosts a projection of the performance La Vittoria, which took place originally in Milan in 1970: a huge penis ejaculating fireworks right next to the Duomo cathedral, celebrating the death of New Realism.

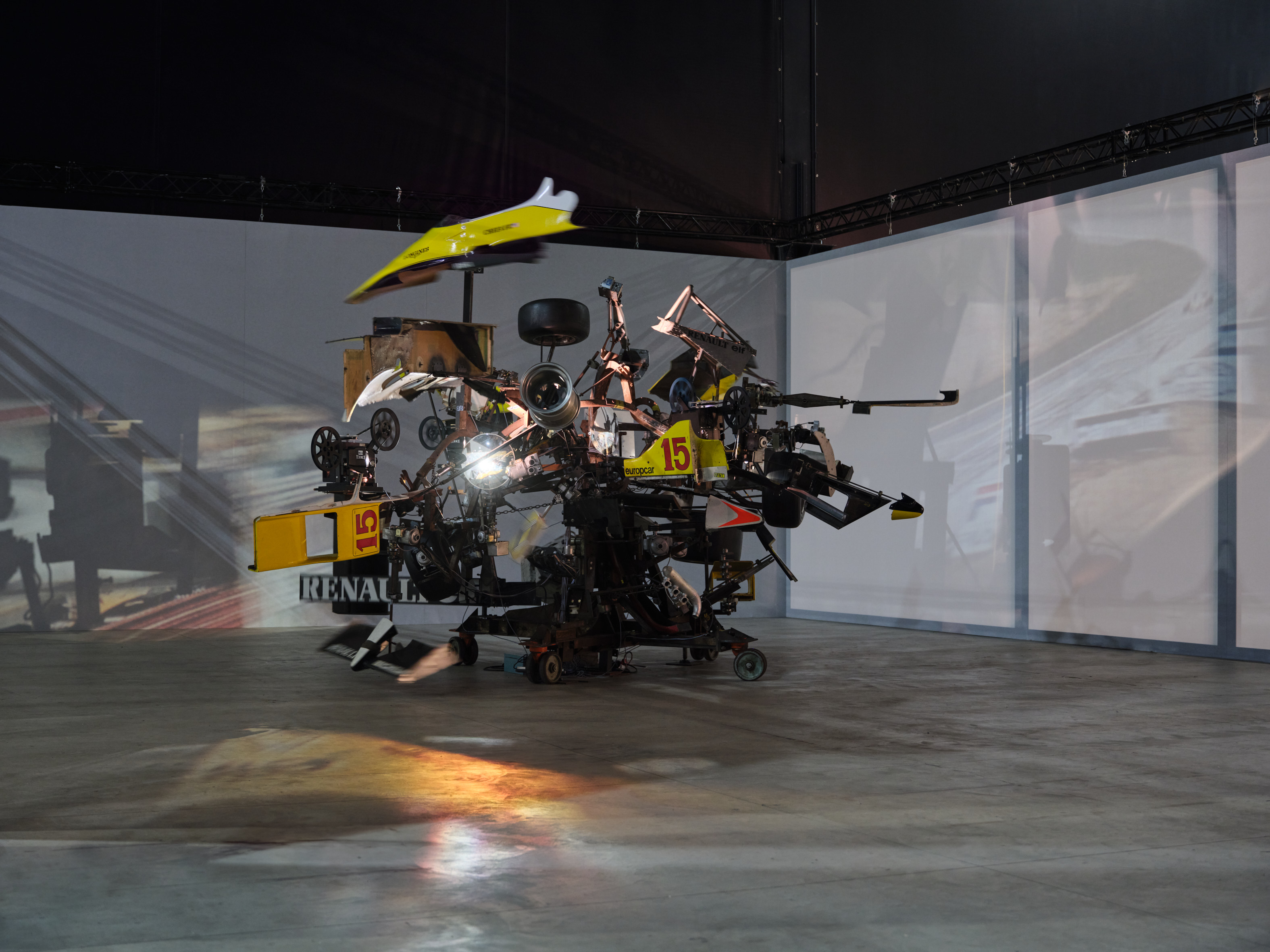

Visitors walk through the works on display without a timeline or any continuity. They celebrate slowness as opposed to today’s frenzy. The deconstruction of a Formula 1 car is the apotheosis of organic chaos (Pit Stop, 1984). Jean Tinguely reassembled the parts of the Renault RE 40 racing car in a disorderly fashion, contrasting it with a shot of the same car ‘flying’ around the Monza racetrack and being repaired in the pit. Next to it, spinning in a vertical spiral, is the sculpture Schreckenskarrette – Viva Ferrari (1985), in honour of the Italian racing team.

“If you respect it, if you put yourself in play with the machine, then perhaps you’ll be able to give life to a playful machine – and by playful, I mean free,” theorised Tinguely.

Medical support

In other works, the visitor actively participates by pressing a button with their feet, switching on the gear and bringing the sculpture to life, as in the Maschinenbar table (1960-85). Méta-Matic No.10 (1959), on the other hand, was out of action, breaking down and being treated by the works’ ‘doctor’, Jean-Marc Gaillard, chief-conservator of the Tinguely Museum’s collection.

“My healing tools are simple: screwdrivers, pliers… you need to connect your hands to your mind through your heart to love these works and listen to them. I usually arrive early in the morning, sit down or walk through the spaces and say ‘good morning’ to the works. And I stay there, listening to them, to feel when something isn’t as it should be,” he says during the pause of a small repair on the kinetic sculpture Rotozaza No 2 (1987).

Gaillard has a musical ear and lives among the cries and whispers of these mechanical creatures. “Sometimes they catch a cold, like us. Then I take them out of the exhibition,” he says, after recommending rest to Méta-Matic No 10. When he’s not restoring works by Tinguely, Gaillard scours the world for look-alike elements and twin parts.

“I only use old materials to eventually replace a piece. I always need to have something like the original. Animal skeletons, wooden wheels. My biggest problem is securing a stock for the future, for the next 40 years,” concludes the “doctor”.

Tinguely’s life and work were deeply interwoven in his relationship with the artist Niki de St. Phalle. More on the artist duo you will find here (with video):

More

Niki de Saint Phalle’s art remains larger than a grand Zurich show

Edited by Virginie Mangin/ac

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.