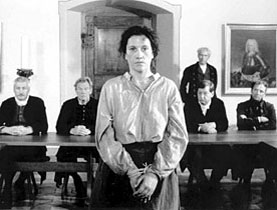

“Last witch” to be declared innocent

The central canton of Glarus will officially exonerate Anna Göldi on Wednesday, more than two centuries after she was beheaded for poisoning a child.

Regarded as the last witch to be executed in Europe, Göldi’s case in the village of Mollis in 1782 was a tragic illustration of religious fanaticism, superstition and the abuse of power.

The case received renewed attention after local journalist Walter Hauser published a book last year presenting new evidence about the undue influence Göldi’s master had over the village authorities.

Hauser told swissinfo what drew him to the story. “Firstly I come from canton Glarus, it’s my home, and I am also a lawyer and that’s why I wanted to research this case. You could say that I was predestined to write about this subject.”

This week’s recognition that Göldi was the victim of judicial murder comes after a long debate. The decision was taken in consultation with the Protestant and Roman Catholic churches.

It is not the first time the powers-that-be have weighed up the issue. Last year the cantonal government and the Protestant Church council rejected a call for exoneration. The government changed its view after the cantonal parliament urged it to reconsider. On behalf of the executive the parliament will now go ahead with Wednesday’s vote to clear Göldi’s name.

“I’m very pleased that the government of Glarus have changed their minds since last year and said yes that Anna Göldi is innocent and the victim of a scandalous miscarriage of justice,” Hauser said.

Bewitching

Göldi, a 48-year-old servant in the house of prominent citizen Johann Jakob Tschudi, was convicted of “bewitching” the family’s eight-year-old daughter, causing her to spit pins and have convulsions.

Tschudi, a doctor and magistrate, apparently had sexual relations with Göldi, and his reputation would have been seriously damaged if the adultery became public.

Even before falling into the hands of Tschudi, Anna had a miserable life story. Born to a very poor family, she was sent into service as a young girl. Unmarried, she hid her first pregnancy and gave birth alone but suffered public disgrace when the baby’s dead body was discovered.

Three years later, she again became pregnant – this time by the master of the house she was working in. The fate of her second child is unknown. She changed jobs several more times and ended up in the Tschudi household where she spent six years until she was fired, blamed for the illness of one of the children.

Göldi’s trial and beheading in 1782 was carried out at a time when witch trials had disappeared from the rest of Europe. The last women to be executed for witchcraft in Germany died in 1738.

Illegal trial

The Protestant Church council, which conducted the trial, had no legal authority and had decided in advance that the woman was guilty, said a strongly worded statement from the Glarus administration earlier this month. She was executed even though the law at the time did not impose the death penalty for nonlethal poisoning, it added.

“This is to acknowledge that the verdict ensued from an illegal trial and that Anna Göldi was the victim of ‘judicial murder’,” the statement declared.

“Exoneration is to be more than a simple confirmation of innocence,” it continued. “It has to set aside an incomprehensible, unjust state act and acknowledge a crass injustice and seriously false verdict.”

But the Glarus authorities noted that the exoneration should not give the impression that today’s generation assumes responsibility for the history of the ancient villagers.

Far from being the preserve of the Middle Ages, persecution on the grounds of witchcraft continued to much more recent times.

Though witchcraft was long viewed as a form of heresy, it was only criminalised after 1500 and the high point of the purging of witches came in the 17th century.

Protestant and Catholic churches pursued the cause with equal fanaticism, perhaps sparked by the Reformation.

The victims of these trials – numbering tens of thousands – were mostly women, however an estimated 20 per cent were men.

A museum on Göldi was opened in Mollis last September, 225 years after her death.

There is some confusion over the correct version of Anna’s surname. The name Anna Göldin was popularised after Eveline Hasler’s book of the same title. This followed the old practice of informally making women’s surnames feminine (Mr Blumer, Mrs Blumerin).

However, as Anna’s birth certificate shows, the correct surname is Göldi.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.