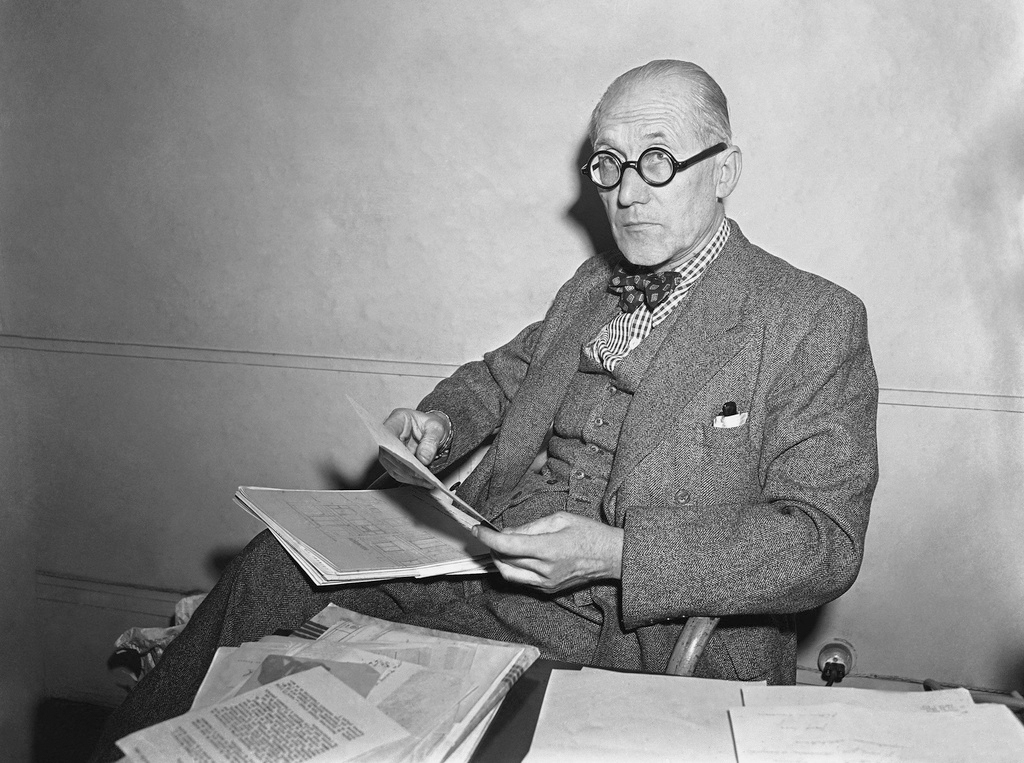

Le Corbusier: unravelling the myth

The 50th anniversary of Le Corbusier's death has sparked a huge controversy in France about his relationship with the Vichy regime. Three new books cast a harsh light on this Franco-Swiss architect, while an exhibition at the Pompidou Centre turns a blind eye to his darker side.

The polemic has reached such proportions in the last weeks that some French media are deliberately “forgetting” the French nationality that Le Corbusier – whose real name was Charles-Edouard Jeanneret – acquired in 1930, and are referring to him simply as a “Swiss architect.”

“I’ve noticed that when it suits some people, he becomes Swiss again,” comments Xavier de Jarcy, Télérama journalist and author of Le Corbusier, External linkun fascisme françaisExternal link (Le Corbusier, a French Fascism). The book’s title is printed against the French Tricolour, leaving no room for ambiguity. According to the author, the architect “felt more French than Swiss.” Indeed, for many years he had tense relations with his country of origin, in particular with La Chaux-de-Fonds in the canton of Neuchâtel, where he was born in 1887.

Le Corbusier’s dark side

“In Switzerland people started talking about Le Corbusier’s dark side much earlier,” explains de Jarcy. In France, which adopted Charles-Edouard Jeanneret and gave his work an international sounding board, the debate has taken longer to emerge. But it has now reached such a magnitude that the Le Corbusier Foundation felt obliged to issue a statementExternal link at the end of May setting the record straight. It stressed that the foundation had made all the architect’s correspondence available to researchers without trying to hide anything. It “considers that keeping Le Corbusier’s heritage alive should not lead one to underestimate or mask certain aspects of his character or behaviour.” But it also calls for “a dispassionate and scientific approach towards a particularly complex period.”

The architect certainly never left anyone indifferent. “He always provoked,” acknowledges Michel Richard, the director of the Le Corbusier Foundation, nestled in a pretty cul-de-sac in Paris’ 16th arrondissement. “People were either strongly for him or strongly against. There were extremes on both sides.”

Yet the left-wing Gaullist intellectual André Malraux praised him at his funeral in 1965, recognizing that: “Le Corbusier has had great rivals […] But no one else has so forcefully signified the architectural revolution, for no one else has been so long and so patiently insulted.” These were the words of a man who fought in Spain against the fascism whose very theses Le Corbusier had at the same time defended.

More

Paris looks back at Le Corbusier

Triumphant ideas … after the liberation

Such is the paradox of the architect from La Chaux-de-Fonds: his architectural ideas triumphed after the liberation, during the “glorious thirty years” when France was being rebuilt on the battlefield of the Second World War. His relationship with the far right was forgotten; his stay in Vichy during the occupation, at the heart of the Pétain regime, was also erased. At the time of his funeral, Le Corbusier was revered in France. It took nearly half a century for his past to be exposed. Only now has research into the correspondence available at the Foundation that bears his name revealed his hidden face to the public.

His writings provide clear evidence of his views. “The military defeat is a miraculous French victory in my eyes,” he wrote to his mother in summer 1940, just months after the French rout by Hitler’s troops. Worse still, his private correspondence contains openly anti-Semitic statements: “Money, Jews (partly responsible), Freemasonry, all will face justice. These shameful fortresses will be dismantled. They dominated all.”

Some months later, during the early months of the Nazi occupation, he recognized that “the Jews are having a hard time,” but immediately added that “their blind thirst for money had rotted the country.” The journalist de Jarcy has collected these statements in his book. Whereas the architect’s cousin Pierre Jeanneret quickly joined the resistance, Le Corbusier himself took up residence in Vichy in January 1941. He wasn’t forced to. It was his choice, says de Jarcy.

The wish to collaborate

“Le Corbusier did not find himself in Vichy by chance. He and his friends felt that the long-awaited moment had arrived. They said it clearly. For 15 years they had been waiting to implement their programme, as defined in the journals Plans and Prelude,” explains de Jarcy. “The revolution that they wanted was essentially embodied by urban planning, giving material form to an ideology that was based on a return to patriarchal values, such as work and the family.”

In the journalist’s view, when Marshall Pétain took power Le Corbusier “evidently wanted to collaborate.” But Vichy was not necessarily interested in his architectural plans. “The regime had its own ideas, which did not necessarily coincide with Le Corbusier’s,” he notes, differentiating nonetheless between the architect and the “collaborators” that acted as informers during the occupation. ”There were others much worse than him. He did not collaborate with Germany.”

After the liberation of France, Le Corbusier emerged unscathed. “The purge affected only the most serious cases,” notes the journalist. In the opening pages of his book he recognizes that “fascism does not prevent talent,” citing another controversial example, the writer Charles-Ferdinand Céline.

Exhibition overshadowed

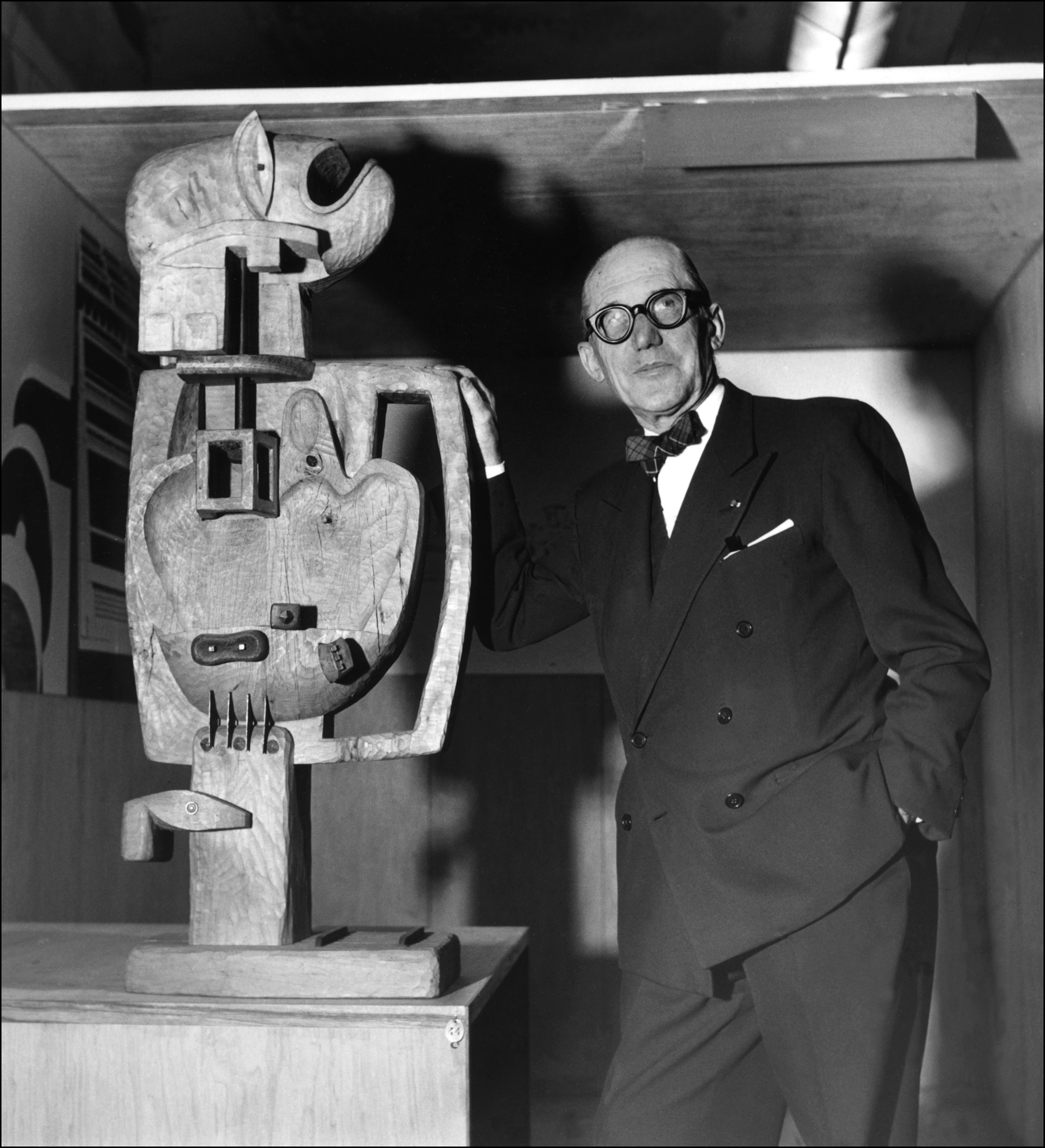

In parallel to de Jarcy’s book, two other works critical of the architect have appeared: Corbusier, une froide vision du mondeExternal link (Corbusier, a Cold World View) by Marc Perelman, and Un CorbusierExternal link (A Corbusier) by François Chaslin. This unravelling of the myth surrounding Le Corbusier has pretty much eclipsed the exExternal linkhibitionExternal link being held at the Pompidou Centre until August 3 and the activities planned in different locations across France, such as Ronchamp in the Jura near the Swiss border, where he built a chapelExternal link. The controversy did not, however, prevent a sculptureExternal link by Le Corbusier from being sold for CHF3.1 million ($3.3 million) at an auction in Zurich in early May.

The exhibition at the Pompidou Centre does not deal with the Neuchâtel citizen’s controversial past. The organizers point out that his behaviour under Vichy was treated in a major retrospective in 1987. Today another angle is being explored. Entitled “The Measures of Man,” the exhibition features paintings, sculptures, scale models, furniture, architectural drawings and plastic art.

Turning the page

The journalist de Jarcy regrets that Le Corbusier’s dark side is not mentioned at the Pompidou Centre exhibition. “I believe there is a direct link between his ideas and his urban planning. We cannot overlook it.” He goes further in his book. There he calls for all French streets that bear the name of Le Corbusier, or of other artists involved in Vichy, to be renamed. “The time has finally come to turn the page,” he concludes.

Translated from French by Julia Bassam

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.