Mummy discovery reveals ancient secrets

A Swiss team has uncovered a mummy in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings – the first of its kind since the exhumation of Tutankhamen in 1922.

The Valley of the Kings is like a Holy Grail for Egyptologists. Situated on the west bank of the Nile, opposite Luxor, it is the burial site of many pharaohs and members of royal families or powerful nobles of the Egyptian Empire.

It was here, in 1922, that the most famous discovery in the history of Egyptology was made: the tomb of Tutankhamen, which until now has been the only intact example of its kind.

The latest find, which has created quite a stir, began on January 25, 2011, as part of clean-up work by a team of researchers from Basel University.

“On this famous January 25, we were cleaning a previously discovered tomb,” Susanne Bickel, professor at Basel University and head of the Swiss archaeological team, told swissinfo.ch.

“We were building a low wall around the tomb when all of a sudden we hit the upper edge of something…”

Bickel said they first thought they were dealing with rubble or an unfinished building.

“Imagine our surprise when we realised it was probably another tomb. We’d never have thought two tombs could be so close to each another.”

But initially the find remained in the sand. At the beginning of 2011, Egypt was in full revolution; rumours of pillaging spread. Out of concerns for their safety, the team returned to Switzerland. A metal cover was placed over the opening to the tomb and the experts waited for a more favourable time to go exploring.

Intact

This turned out to be January 2012, when the team received official authorisation from the Egyptian authorities to carry on with the excavation.

“We were in a hurry to find out what was in the tomb,” Bickel said. “It took us four days to cross a well shaft. We managed to slide an arm in to take some photos with a camera. We saw an untouched tomb and a sarcophagus which was completely intact – unlike most of the ones we usually see.”

The team, protected from the searing desert sun by a tent, described a sarcophagus which was quite soberly decorated, without any embellishments.

“There’s no decoration on the sides,” said one researcher. “It’s very thick, very beautiful wood. We knew the tomb had been built in the 15th century BC, but we’ve discovered that the sarcophagus dates from the ninth century BC.”

This meant they could deduce two significant facts, he added.

“We’ve concluded from the fact that the tomb dates from the 15th century BC that there was a second burial 500 years later,” he said.

“Second, the simplicity of the sarcophagus makes us think that in the ninth century, during the 22nd Dynasty, a burial consisted of a humble sarcophagus and a simple stela [a sort of gravestone]. Unlike in the 15th century, during the 18th Dynasty, when ceramics and personal property were very popular.”

Singer?

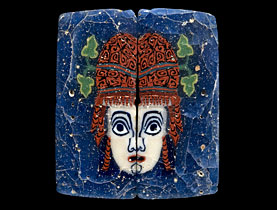

Having examined the inscriptions, which have yet to be completely decrypted, the scientists say they are dealing with a woman called Nehemes-Bastet, which means “May the goddess Bastet protect her”.

“What is astonishing is that the sarcophagus is two metres long, but the mummy, which is perfectly preserved, is only 1.55m,” Bickel said.

“We think the deceased was a singer for Amun-Ru [one of the most widely recorded Egyptian gods]. Her title shows she was part of the elite. She probably acted as a priestess from time to time during major processions.”

Bickel said it was the first time a tomb had been found in the Valley of the Kings of a woman who was not linked to the royal families.

Secrets

The aim of the Basel University project is to analyse the non-royal tombs found in the side valley leading to the tomb of Thutmose III, the sixth pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty. Until now, these tombs have hardly been studied.

“Many are even completely unknown,” Bickel explained. “We search them, document their architecture and try to find among the tonnes of debris some signs that enable us to say what they were used for – and possibly the person or people who had the privilege of being buried in this valley, near the pharaohs.”

The discovery of the sarcophagus belonging to Amun-Ra’s singer turns the spotlight on another period of the valley’s history: that of the ninth century BC, when the tombs were re-used for a second time.

The mummy has yet to be analysed. Much remains to be learnt from the woman who escaped the pillages and struggles of the time to reach us intact and reveal a few of her secrets.

Skin and dried flesh have been preserved by exposure to chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity, or by lack of air when submerged.

The best-known mummies are those that were embalmed for preservation, particularly those in ancient Egypt. This concerned not just humans but also crocodiles and cats.

In China, preserved corpses have been recovered from wooden coffins found underwater and packed with medicinal herbs.

Although Egyptian mummies are the most famous, the oldest found are the Chinchorro mummies (up to 7,000 years old) from northern Chile and southern Peru.

(Translated from French by Thomas Stephens)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.