Nazi art: ‘Bern can be an example for the world’

He was a quarter-Jewish Communist who rose to become one of Hitler’s four official art dealers. A new book looks at the fascinating rise of Hildebrand Gurlitt, whose collection of masterpieces was discovered in 2012 and left to a Bern museum.

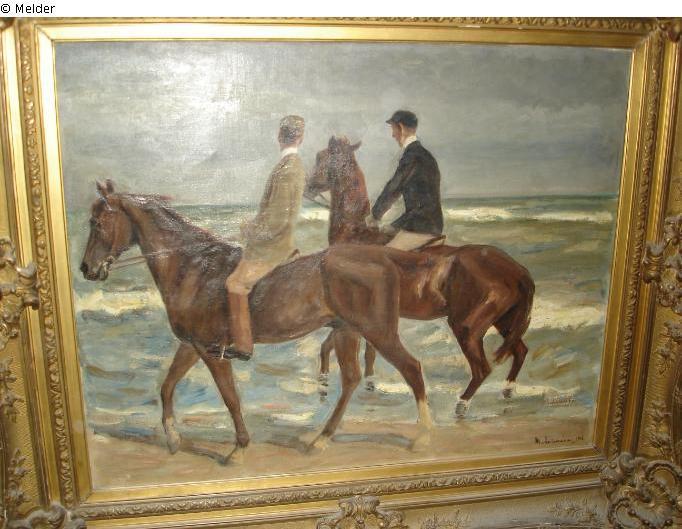

The 1,280 works of art found by surprised tax investigators in the Munich flat of Hildebrand’s reclusive son Cornelius – including pieces by artists such as Picasso, Renoir and Matisse – have been described by Ronald Lauder, head of the World Jewish Congress, as “the last prisoners of World War II”.

In her book, The Munich Art Hoard: Hitler’s Dealer and His Secret Legacy, Berlin-based journalist Catherine Hickley painstakingly traces the collection’s history and examines the legal and ethical challenges of dealing with looted art.

Readers are taken from the anti-Semitism of pre-war Germany, where many desperate Jews were forced to sell their possessions at ridiculously low prices, to the dilemma of the Bern Fine Arts Museum, who last November finally said it would accept the collection left to it by Cornelius in his will.

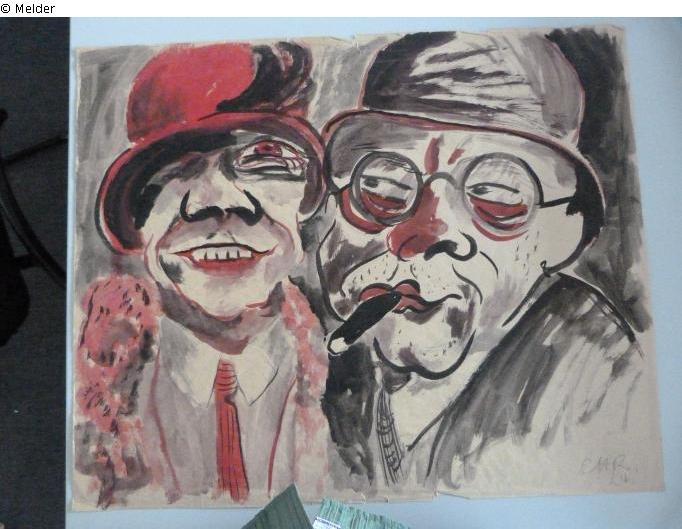

Along the way Hickley unravels a “man of contradictions”: Hildebrand was the first German museum director to be fired for championing the “degenerate” art hated by the Nazis but was later accused of being an unscrupulous opportunist only to be cleared by the Allies after the war. He ended up dying in a car crash in 1956 aged 61.

Catherine Hickley

Catherine Hickley is one of the world’s leading journalists in the field of Nazi-looted art. She occasionally writes for swissinfo.ch.

In a 16-year career at Bloomberg News, she reported on arts and culture from Berlin for eight years.

She witnessed the fall of the Berlin Wall as an English teacher in East Germany in 1989.

swissinfo.ch: When the news broke of the Munich art hoard in November 2013, it was clear there was a great story to be told. But although all the headlines were about Cornelius Gurlitt, your book focuses on his father.

Catherine Hickley: Five of the first six chapters focus on Hildebrand Gurlitt. It became clear to me that he was really the interesting character behind all of this. Cornelius was by far the more tragic figure: he led this very lonely life – he was a complete recluse – and had inherited this huge responsibility from his father and couldn’t really cope with it, especially towards the end of his life.

Hildebrand Gurlitt was the ambivalent, paradoxical one who really interested me. What I was trying to find out was how this man who was basically an anti-Nazi – he was fired from one job because he had the flagpole sawn off the front of his gallery because he didn’t want to have to hang the swastika – he was maybe even a Communist, he was a quarter Jewish, he loved this art that the Nazis hated: how could someone like that end up working for Hitler and buy art for the FührermuseumExternal link in Linz?

I found out it was a combination of greed and ambition and the desire for status that led him to make some fairly terrible compromises with his integrity. There’s no question that he bought art very cheaply from Jews who were trying to leave the country and then sold it on at a profit. And there’s also no question that he bought art that he knew had been stolen from Jews.

More

When owning works of art isn’t black and white

This showed me that when you’re operating in a criminal regime, when you’re working under those situations in a totalitarian government, the only way to advance is to make some pretty severe compromises ethically.

To do the right thing – to be moral – you would have to prioritise that above everything else, and that, in many cases, would actually mean risking your life. And as we know, most people didn’t do that. So to me, Hildebrand Gurlitt is one of many, many Germans who made those kinds of compromises rather than stick his neck out and take a risk by opposing the regime publicly.

But I don’t think he was one of the great evil-doers. I think he was someone who allowed his moral compass to go completely astray just because he was trying to advance in an evil regime.

swissinfo.ch: That said, after the war he didn’t exactly go out of his way to help Jews looking for their paintings. That was a good chance to make amends, wasn’t it?

C.H.: Yes, and this is the thing that I think is most unforgiveable about his career, that when Jews who had sold artworks to him came to find him after the war to ask him where their artworks were and what he’d done with them, he refused to provide any information. He often got lawyers to answer their letters and said he didn’t remember what had happened [to the art] and that all his business books had been burnt in the war.

So at a time when he could have helped the Jews without fear of reprisals, he didn’t – and that seems pretty unforgivable.

swissinfo.ch: The Gurlitt collection had been an open secret in the art world for decades. Had nothing been written about it before?

C.H.: No. The dealers who knew about it weren’t aware of its dimensions. They knew there was this collection and they knew about some of the artworks, but I don’t think anyone actually knew the scale of it.

But it’s still surprising that people knew about it and it never got written about, or no one ever thought to enquire more deeply about the whereabouts of all of this art.

More

Inside the Gurlitt collection

swissinfo.ch: What lessons have been learnt from the Gurlitt collection?

C.H.: Well at the moment I’m questioning really how far the lessons have been learnt. When I wrote the book I was a lot more optimistic, but in the past six months a lot of things that I was hoping would have happened by now haven’t. Only two of the pictures in the Gurlitt collection have been returned, which is a bit of a lame record really. There are two more that we know are looted art and they still haven’t been returned.

The whole bureaucracy involved in actually conducting the restitutions has been just dreadfully slow and dreadfully obstructive. So the claimants have all got incredibly frustrated by that.

swissinfo.ch: Has there been a shift in attitude in Germany towards suspected looted art?

C.H.: There’s been a huge shift in attitude, and that’s one of the things that one has to welcome. I also think the ruling classes have become extremely aware of the problem and also the risk to Germany’s reputation of doing this wrong. However, I’m sure they’re all hoping like crazy there won’t be another Gurlitt case, because the whole thing could happen all over again because nothing has changed in the legal system.

Gurlitt family

Cornelius Gurlitt (1932-2014) was born in Hamburg to Hildebrand Gurlitt (1895-1956), one of four official art dealers for the Nazis, and Helene Gurlitt (1895-1968), a dancer. He had one sister, Renate, known as Benita, (1935-2012).

Hildebrand’s sister, Cornelia (1890-1919) was an artist. His brother, Wilibald (1889-1963) had four children.

Cornelius’s grandfather, also called Cornelius (1850-1938), was an architect and art historian.

His great-grandfather, Louis Gurlitt (1812-1897), was a Danish-German landscape painter whose brother, yet another Cornelius (1820-1901), was a composer.

The other thing that has changed is that much more money has been made available for provenance research. The budget from the federal government and from the states for provenance research in museums has been boosted [trebling to €6 million (CHF6.5 million) in 2015], and this is hugely important. It means museums will really have to start doing their work on provenance. Some of them have already done it – I don’t want to say German museums don’t do provenance research at all – but there are plenty of museums that haven’t done nearly enough, and this is an incentive for them to do it, because they’ll actually get funding for it.

swissinfo.ch: You write that putting museums in charge of the restitution of looted art is like putting a fox in charge of the henhouse…

C.H.: Museums see their duty as preserving their collections – that is their primary mandate. Only some museum directors would view the moral prerogative to hand back Nazi-looted art as a higher priority. And this is often a problem: people don’t want to lose the most valuable works in their collection because of a claim. And of course the people who don’t want to lose works should not be the ones deciding whether the works should be returned. There’s something deeply wrong with that situation.

swissinfo.ch: It’s been a year since the Bern Museum of Fine Arts decided to accept the Gurlitt collection, which Cornelius had left it in his will. It is currently involved in various legal issues – some relatives are saying he wasn’t of sound mind when he wrote his will – and not a single painting has been put on display. Do you think it regrets saying yes?

C.H.: I hope not. My wish would be that the Kunstmuseum in Bern sees this as a fantastic opportunity. First of all because it’s a great collection, but secondly to do the right thing and show how it should be done. And that means exhibiting the art, of course, but also putting the provenance details of every single artwork in that collection online. It means inviting information from other people, it means asking claimants to come forward. It actually means going in search of claimants if possible.

But if you do it right, and if you have the right resources to do it – which I think Bern does have – then you could really set an example to the rest of the world and at the same time have this wonderful art collection, which definitely complements the collection in the Kunstmuseum very well.

swissinfo.ch: The public wants to see some of these paintings. When will that happen?

C.H.: At this stage we just don’t know. It’s all rumours until the court in Munich reaches its decision [over the will claim], and it looks as though there might be a decision in February, but we’ll see – it could easily get delayed for any number of reasons. But if that does go through, I hope very much there will be an exhibition very soon afterwards.

It’s obviously something that has to be thought about extremely carefully and done with extreme tact and diplomacy and involving potential claimants.

Timeline

September 22, 2010: German custom officers carry out a routine search of passengers on a train from Switzerland and find 77-year-old Cornelius Gurlitt with €9,000 (CHF10,800) in cash (below the €10,000 reporting limit). Suspicions are raised of tax evasion.

February 28, 2012: The authorities enter Gurlitt’s flat in Munich and discover up to 1,400 works of art, many thought to have been lost in the war. The discovery is kept secret, while an expert gets to work on the art’s provenance.

November 3, 2013: German magazine Focus reports the story, which gets headlines around the world.

January 28, 2014: A task force reveals that following an initial examination, 458 works are suspected of being looted.

February 10, 2014: More than 60 valuable paintings, including works by Picasso, Renoir and Monet, are found in Gurlitt’s house in Salzburg. It later turns out the Austrian property contained 238 works in total.

April 7, 2014: Gurlitt’s lawyers reach an agreement with the German government, whereby Gurlitt would voluntarily return looted artwork to the heirs or previous owners.

May 6, 2014: Gurlitt dies aged 81 in his Munich flat, having not seen his paintings since they were confiscated two years previously.

May 7, 2014: Gurlitt’s will names the Bern Museum of Fine Arts sole heir of the collection. The museum says it will take a decision on accepting the collection by the end of the year.

November 21, 2014: Uta Werner, Cornelius Gurlitt’s cousin, contests the will, saying Cornelius was delusional when he wrote it. If successful, she would be entitled to half his legacy. The other half would go to her brother (who didn’t challenge the will and wants Bern to keep it).

November 24, 2014: The board of the Bern Museum of Fine Arts said it would accept the collection.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.