Nothing is possible: Swiss animator explores the limits of virtual reality

Fabienne Giezendanner, whose project Bloom recently featured at a virtual reality (VR) festival in Prague, discusses the challenges of combining art and technology, the VR situation in Switzerland, and why having two passports is a “great stroke of luck”.

Virtual reality is an art form bound to the technology that gives it shape. Watching a VR or XR (extended reality) “experience” involves slipping on a plastic VR helmet. If this device malfunctions in the slightest, if wires become entangled around ankles or wrists, or even if the outside world intrudes through noise or bodily sensation, the thread of illusion is promptly severed.

And if an artist wants to create a VR experience, it certainly helps if they have some knowledge of the programming technology involved. If their ambitions exceed their technological competence, they must enlist the help of a developer, whose technical realism may also restrict the artist’s vision.

At ART*VR – the Festival of Virtual Reality and Immersive Art in Prague, which took place in October – these limitations of the form were on my mind. The festival takes place in a modern art museum, DOXExternal link, and is divided into a fixed exhibition, where a selection of curated projects can be accessed freely by putting on any headset, and a competitive section spread out across a floor of the museum, with one project per headset.

Though VR is still perceived as the most futuristic of art forms, its technology remains stubbornly primitive. Projects rarely exceed 25 minutes, due to technical limitations, the discomfort of the headsets, and very real concerns about nausea. Most projects are either computer animations or photorealistic mini-films, shot with 360° cameras in the real world.

More

Nausea-free VR: how far has research progressed?

And there’s no getting around it: the graphics that animate the former would not look out of place in a video game from ten or 15 years ago. The latter, despite their pretentions to hyperrealistic immersion, are scarred by obvious artefacts of compression – skies are filled with pixels, for instance.

Headsets are produced by Meta, the parent company of Facebook, which also dominates the distribution and production marketplace.

Portrait of a Swiss as a VR artist

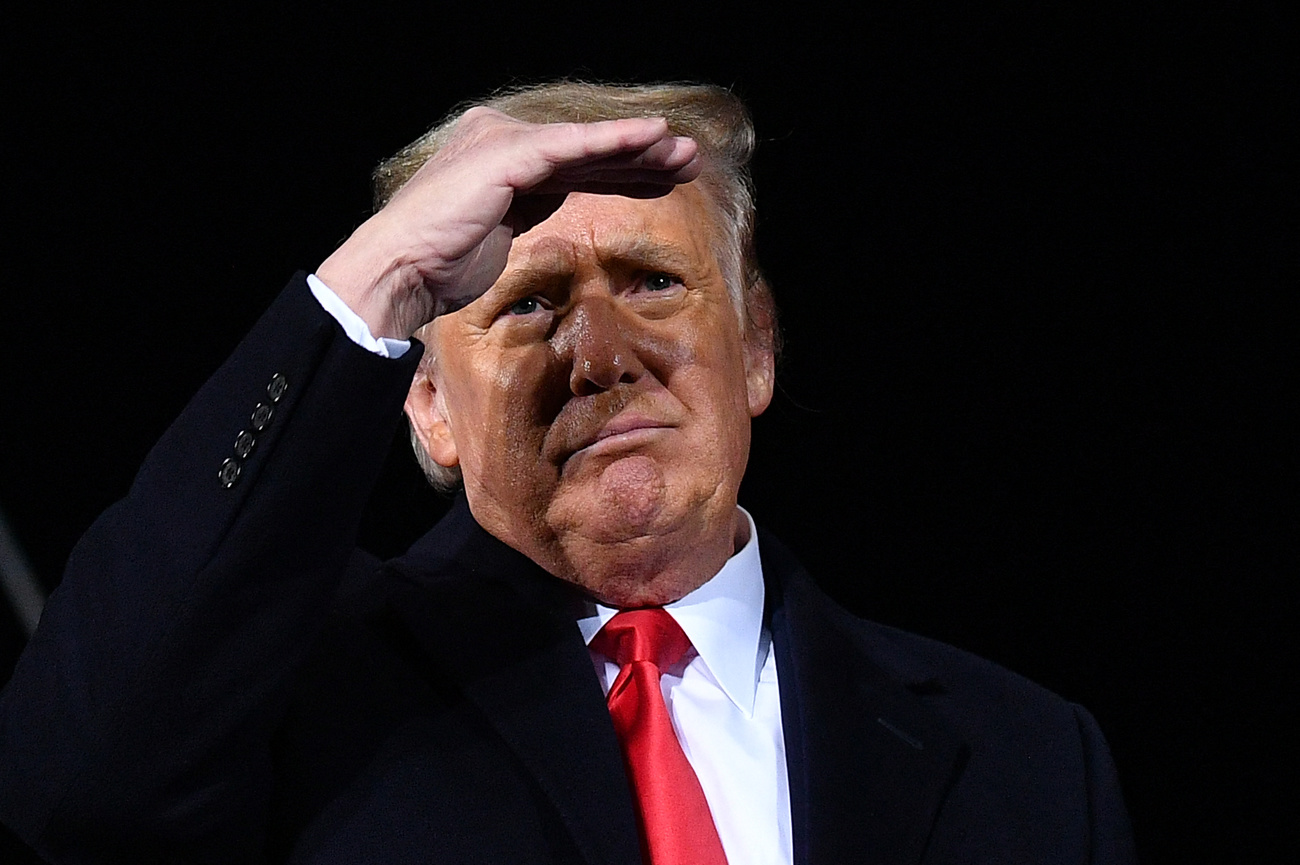

Among the projects shown at the Prague festival was Bloom (2023) by 57-year-old Swiss-French animator Fabienne Giezendanner. A successful 2D animator, she was drawn, in her early fifties, to the possibilities of art-making in the virtual space. When I spoke to her in Prague, I was surprised by just how much Giezendanner emphasised the extent to which her work is now constrained by the possible.

“As an animator, it can be quite frustrating,” she told SWI swissinfo.ch. “I might ask my designer for ten birds, and because the have to be so small, he tells me, no, it must be three. When I started [in 2016], it was much worse, of course. But even today, you have to keep it to around 200 megabytes per clip. It’s very difficult and means we must adapt what we have all the time.”

Then there are the formal, narrative qualities inherent to the form. “It’s a challenge [for an immersive artist] to write scripts in the conditional tense – ‘if, then’. That means one must think this way: if the viewer looks at this bird animation, then another animation must begin. When you engage in this thinking for too long, you get a headache,” she laughs. “But in the evening, when eating dinner, you might finally begin to understand all the possibilities you have at your fingertips.”

A digital forest in bloom

Virtual reality is in its infancy, and most projects fit recognisable patterns. Heavy topicality of theme is an obvious one. The film critic Roger Ebert once labelled cinema “a machine for empathy”, and that has become a common way VR is mythologised.

Viewers are dropped into the shoes of those, say, suffering from miscarriages or postpartum psychosis, or made witness to the social mistreatment of Korean comfort women – to cite a few examples in the Prague showcase. Even a loose, richly textured, and more self-consciously experimental work such as Lee Sang-hee’s Oneroom-Babel (2023) is described, in its synopsis, as a response to the contemporary housing crisis.

Bloom immerses us in a living climate nightmare. You stand on the streets of Ornans, France, where Giezendanner lives. The Gustave Courbet Museum – the 19th-century French artist was born in the town – is visible in the distance, smouldering. Pale cinders twist in the air. In the distance, the blare of emergency, the din of panic. A bird appears, guiding you into a forest as respite from the heat. I peer at my hands – my real hands, behind the visor. Twigs protrude from them. My wrists are covered in moss. My whole left hand has begun to bloom with flowers; I have become the forest.

I ask how a successful 2D animator tackles the challenges and limitations of a virtual form. “First, I write the story”, Giezendanner says. “Then [my collaborators and I] begin to assemble the sounds, start work on the basic animations – for example, of the bird who triggers the action that I mentioned before. Start talking to the animator, or the guy who makes the backgrounds. And the Unity developer [game engine designer] can also get an idea of the in-world triggers you have in mind.”

More

Inside the headset of Swiss VR animator Zoe Roellin

VR-making in Switzerland

Giezendanner was born in Switzerland, but she now lives and teaches in France. Her reasons are pragmatic. “I have both a Swiss passport and a French one,” she says. “I move between the two countries, [depending on where] it’s easier to find funding. If I find a producer in one of the two countries, I myself can be the co-producer, and that gives us two countries, which makes everything easier. For an artist, having two passports is a great stroke of luck.”

The community for immersive fiction is still nascent in Switzerland. While there are a few crucial engines underwriting the expansion of the practice and distribution of VR works, it is still in the early stages.

“In France, there is already a big community. There are co-producers, funding, wonderful curators. Switzerland has the GIFF [Geneva International Film Festival, where Bloom premiered], which is great,” Giezendanner says. “But yes, we’re just at the beginning in Switzerland. Frankly speaking, salaries are higher and there are fewer people willing to produce VR projects.”

Funding is one thing; knowledge is another. As a young form, and one bound up with advanced programming technologies, VR remains unfamiliar and distant to many young artists.

“My students mostly come from cinema, theatre, animation, dance,” Giezendanner says. “When they get started, and start to understand how it works, they think everything is possible. My job is telling them: nothing is possible,” she says, laughing. “They must think about the role of the viewer; they must think in logical progression. I don’t like passive [VR] experiences. I like it when the viewer knows why they’re in the experience.”

Possibilities and pitfalls

All artistic forms are limited, particularly at first, by the technology that enables their existence. As new technologies release artists from the limitations of elementary forms, so their output also becomes more open-ended and complex.

Think of cinema, which is at best a distant cousin to virtual reality, despite superficial similarities. Successful digital movies – such as the popular machinima documentary Grand Theft Hamlet (2024) – can now be produced without cameras, distributed without ever screening in a cinema space (though that was not the case with Grand Theft Hamlet) and still be considered “movies”.

Perhaps I am too firmly embedded in this old world. While watching a project such as Bloom, I find myself distracted by the ubiquitous wires connecting the visor to the headphones or, in the case of other projects, to the PC generating the images. The visor never fits perfectly, so the disembodied effect is undercut by the sight of one’s lap visible through the gap at the end of one’s nose. These inherent technical limitations act as an unwanted barrier to the notion that VR is really an immersive form.

At the same time, the festival offered attendees the chance to take virtual tours through immersive space, following a guide through multi-user VRChat environments that are not constrained by specific time limits.

Despite their decidedly lo-fi look, the chance to move around within meticulously designed digital worlds – closer to video games in this case – clearly delighted those who embarked on the tours. There is, evidently, power in these doors of possibility that are gradually opening, one by one.

More

Cybersickness in virtual reality: why does it happen and how can it be treated?

Edited by Catherine Hickley/ts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.