On the hunt for craft beer in Switzerland

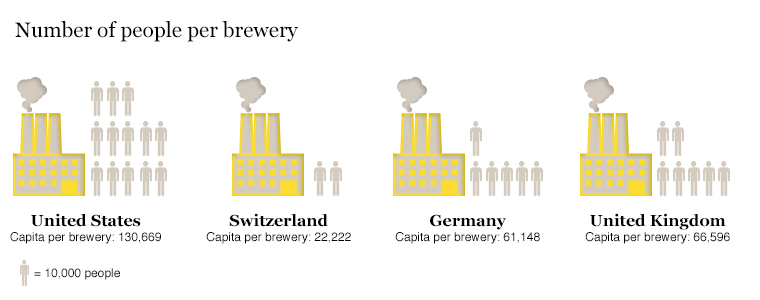

The Swiss have the highest concentration of breweries per capita in the world, yet those seeking everyday beer variety are often left disappointed. Slowly, a burgeoning underground culture is building optimism among craft brew lovers.

It’s early afternoon on a Wednesday in August, and the parking lot of the New Glarus Brewery in New Glarus, Wisconsin, US is chock full. The 20-year-old brewery, perched high on a hill above the Swiss settlement of New Glarus, is a sort of mecca for beer lovers from across the country, as proven by the car licence plates from far-flung locales.

The logo of its flagship ale, Spotted Cow, greets visitors to Wisconsin at the airport and on bar taps across the state and graces the front of T-shirts, mugs, posters and the like at the brewery’s sizeable gift shop. And New Glarus’s creative brews – like “Serendipity,” a fruity summer mix made on a whim with cranberries and apples when the cherry harvest was a bust – attract those looking for something new, who traipse through the extensive brewery tour with their tasting glasses in hand.

On another Wednesday afternoon 7,234 kilometres away in Glarus, Switzerland – where New Glarus’s settlers originated – things are comparatively much quieter at the Adler Bräu brewery, the only brewing operation left in the canton of Glarus, where there used to be more than a dozen. The brewery’s large store with its tasting bar and beers, other drinks and some souvenirs for sale is empty for the moment, and the lunch rush is over at its affiliated restaurant.

But Roland Oeschger, whose family has been part of the enterprise since 1890, says things are going well – his local clientele is very loyal, the beer is selling well and maintains a “very high quality”. Overall, he’s not looking for major change, although he has visited New Glarus and greatly admired the brewery operation there.

Founded in 1828 as part of a restaurant, the only brewery left in canton Glarus today produces 9,000 hectolitres of beer per year which is mostly sold in local-area restaurants, grocery stores and in the enterprise’s large on-site store.

Adler Bräu offers seven yearly beer varieties: a light lager, a dark “special beer,” a light “special beer,” an unfiltered “zwickelbier” and three seasonal varieties for summer, Easter and Christmas.

“We are practically overwhelmed with requests for brewery tours, but we’re not really made for that,” he tells swissinfo.ch. “It’s a question of time, we don’t have the time to lead tours every day – right now, we do a few tours a week.”

And Oeschger expresses the same cautious, wait-and-see attitude when it comes to experimenting with new kinds of beer. Every year, Adler Bräu offers the same seven options, three seasonal and four year-round (see infobox).

“We do contemplate what more we could do, we have a young brewmaster who is interested in doing some experimenting,” Oeschger says. “But we have to be careful to make sure our offering doesn’t become too splintered and we have to think hard about what we are doing.”

“Here, it’s quite difficult to create something that will really resonate with people and stick. We are willing to try some new things but nothing too crazy. If it’s too exotic, it’s probably not really our thing.”

Slow and steady

Indeed, traditional Swiss beer consumers tend to know what they like, stick to it and be suspicious of change – or so they think.

Given that 82.6 per cent of all beer consumed in Switzerland is in the German lager style, introducing something new must be done carefully, like at the Brasserie Trois Dames in French-speaking Switzerland. There, brewmaster Raphaël Mettler won over a traditionalist public by slightly tweaking the balance of the ingredients in his beers over the course of many years in an attempt to improve and innovate his overall product. By very gradually adapting and educating his customers to new styles, he developed an appetite among local beer drinkers for “hoppier,” more daring beers like India Pale Ales and an Extra Special Bitter Ale that’s become the brewery’s staple.

Particularly in countries with a strong beer tradition, the recipe for beer has been the same for centuries: water, barley and hops. (The presence of yeast was discovered much later, by Louis Pasteur in the 19th century).

That formula came about in the form of the Reinheitsgebot, or the German Purity Order, in place since 1487 and originally conceived to make sure beer – the main drink at the time – didn’t contain any impurities that could make people sick.

Not unlike a basic bread recipe, the ingredients in traditional beer are standard but the results can vary wildly depending on a brewer’s skill, creativity and available ingredients.

The Reinheitsgebot is no longer law in Germany, but many brewers in the region – including in Switzerland – still adhere to it for reasons of quality and tradition.

For Gabriel Hill – a Portland, Oregon native who was “hugely disappointed” in the availability of beer in Swiss restaurants when he emigrated to Zurich three years ago – getting a culturally established public like the Swiss to try new styles comes down to education. As half of the two-man team behind the Rapperswil Beer Factory, a brewery on Lake Zurich, he says he’s been successful so far.

“People are interested in knowing about the different beer styles and what goes into the brewing process. That’s been a big change. Before, people would just come up and order a beer – it didn’t really matter what it was.“

“The brewers understand it’s their job to help educate. It’s not just that I brew a beer and people come and buy it. It involves telling the story of what I’ve done to make it.”

Hill also started an annual craft beer festival in 2011, which has more than tripled its original 500-person attendance in the years since. In addition to an increase in numbers, there’s an increase in interest, he says, with people asking about what’s behind the beer and making careful selections instead of just ordering “a beer” for the sake of drinking.

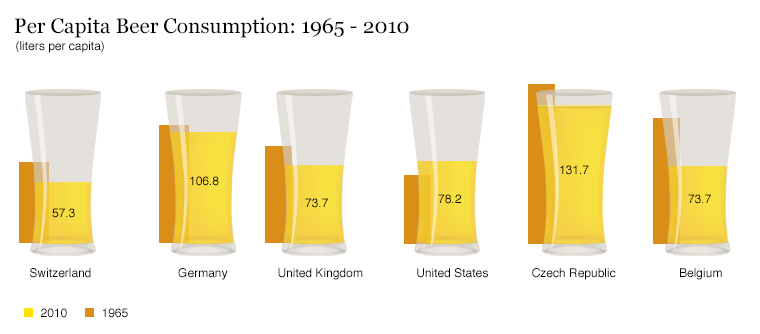

In several places around the world, beer consumption has fallen in the last decade – a phenomenon many beer connoisseurs attribute to the end of beer as a working-class drink and its rise as a specialty beverage to be enjoyed in smaller quantities.

Seeking variety

“Beer hunter” Phillippe Corbat can also attest to change slowly sweeping over the Swiss beer landscape. When he started developing an interest in the brew 30 years ago, a cartel controlled Swiss beer production and distribution, making variety pretty much nonexistent – almost everything was some type of German lager.

Corbat started maintaining a website with a running list of the country’s breweries, visiting as many as he could and leaving a review based purely on personal taste. He wasn’t enamoured with Adler Bräu’s offerings, calling them “weak and unimaginative,” and he criticises several both new and established Swiss enterprises for mediocrity and lack of variety. But, the list also contains more and more breweries deemed “creative” and “interesting,” and Corbat says it’s hard to keep up with all the new beers being made these days.

“There’s been an incredible explosion in the number of breweries,” the beer hobbyist and tasting judge tells swissinfo.ch. “At the end of the 1980s and beginning of the 1990s, I really had to look for new beers. Now they are coming from everywhere, it’s almost too many.”

Fight for market share

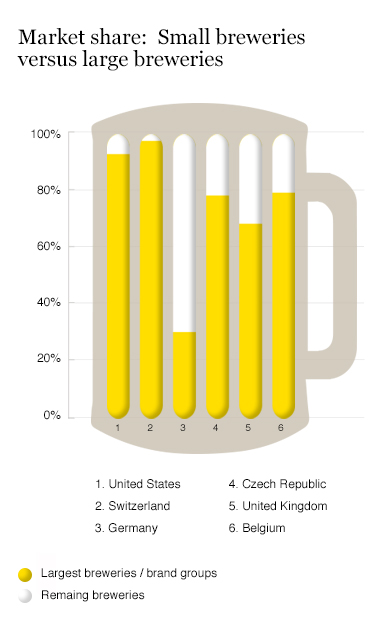

But, when it comes to market share, there’s not always strength in numbers – Switzerland’s 16 largest breweries hold 97 per cent of the market, leaving small, craft brewers to fight for a sliver of the overall beer-drinking public’s attention.

Still, Corbat says that the remaining three per cent of the market is ripe right now, made up of people with a seemingly insatiable appetite for new, local brews, and “small Swiss breweries really have a lot of success” in their local areas as a result.

However, he sees the brewery boom ending in the next five years or so, mostly because many brewers he knows must decide how to develop the enterprise and whether to take the risk of quitting their day jobs to brew full-time and increase their distribution.

“The question is, what is the part of the population can you win?” Corbat says. “In some US cities, it’s pretty high with a 40 per cent market share from craft breweries. I don’t think in Switzerland you can go that far – 20 per cent would be really good.”

Hill is optimistic – he sees the Swiss market share creeping up very slowly and urges patience among the country’s craft beer lovers.

“The increase is modest, but the whole environment is changing,” he says. “Even a small increase in the availability has created more interest. It didn’t happen overnight in other markets where it’s more developed…in Portland, it took 15 years to get to this point.”

Distribution issues

Getting their products into customers’ hands is another hurdle for building craft brew market share among Swiss brewers. According to Hill, a few of Switzerland’s supermarket chains have stocked his products and are becoming interested in offering more beer variety, and things are evolving bit by bit. However, most mainstream Swiss supermarkets still stock based on price and import a huge amount of cheap, lager-style beer from outside Switzerland.

As for restaurants, many of them are locked into contracts with big breweries like Heineken, Feldschlösschen or Carlsberg, which offer them perks in exchange for only serving their products – like a new tap system or bar improvements – that are hard to say no to. Those big breweries are even more eager to lock in restaurant contracts today, given that they’re seeing a lot of pressure on their market share from cheap import brands.

“Nobody has really asked for craft beer before, so the restaurants and grocery stores haven’t seen the market for it,” Hill says. “That makes sense; if no one is asking for it and they don’t think they can sell it, why bother?”

Cultural exchange

Craft beer enthusiasts in Switzerland often wish for the open-minded beer drinkers in so-called “blank slate” countries like the US or Denmark, where there was no established beer culture to dictate taste or tradition. Corbat says he is almost afraid to visit the US for a beer tour because, he says, “I might never come back”.

However, the most successful American craft breweries, including New Glarus, are also looking back to the Old World for much of their inspiration: New Glarus’s brewmaster trained in Munich, and Oeschger says he was impressed by the amount of imported German equipment when he toured the brewery.

And, when Wisconsinites gather in the New Glarus brewery’s courtyard for this year’s Old World-style Oktoberfest celebration, they may be drinking more than just lager – but they’ll be surrounded by a borderline kitschy, amusement park-style replica of a monastery, complete with fake crumbling walls, paying homage to where Germany’s beer tradition originated centuries ago.

Founded in 1993 in the Swiss settlement of New Glarus, Wisconsin, the brewery produces about 100,000 barrels – or approximately 90,000 hectolitres – of beer per year. It offers seven year-round beers, eight seasonal and six specialty brews, four of which are made in small batches as a sort of brewer’s experiment. All are distributed only within the US state of Wisconsin.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.